Beckett, Endgame (1957)

CLOV What is there to keep me here?

HAMM The dialogue.

Postmodernism

[Following dispersal of power in globalism] Postmodernism's adherents often argue that their ideals have arisen as the result of particular economic and social conditions, including what is described as "late capitalism" and the growth of broadcast media, and that such conditions have pushed society into a new historical period. However, a large number of thinkers and writers hold that postmodernism is at best simply a period, variety, or extension of modernism and not actually a separate period or idea.

Postmodern scholars argue that such a decentralized society inevitably creates responses/perceptions that are described as post-modern, such as the rejection of what are seen as the false, imposed unities of meta-narrative and hegemony; the breaking of traditional frames of genre, structure and stylistic unity; and the overthrowing of categories that are the result of logocentrism and other forms of artificially imposed order. (Wikiversity)

Theatre of the Absurd, extracts from Jan Culík:

Defined: 'The Theatre of the Absurd' is a term coined by the critic Martin Esslin for the work of a number of playwrights, mostly written in the 1950s and 1960s. The term is derived from an essay by the French philosopher Albert Camus. In his 'Myth of Sisyphus', written in 1942, he first defined the human situation as basically meaningless and absurd. The 'absurd' plays by Samuel Beckett, Arthur Adamov, Eugene Ionesco, Jean Genet, Harold Pinter and others all share the view that man is inhabiting a universe with which he is out of key. Its meaning is indecipherable and his place within it is without purpose. He is bewildered, troubled and obscurely threatened.

Language: One of the most important aspects of absurd drama was its distrust of language as a means of communication. Language had become a vehicle of conventionalised, stereotyped, meaningless exchanges. Words failed to express the essence of human experience, not being able to penetrate beyond its surface. The Theatre of the Absurd constituted first and foremost an onslaught on language, showing it as a very unreliable and insufficient tool of communication. Absurd drama uses conventionalised speech, clichés, slogans and technical jargon, which is distorts, parodies and breaks down.

Beckett, 1906-1989; Endgame, 1958

Norton 2661: Irish origins; worked with Joyce

-- plays: no progression;

-- Endgame as absurdist drama: peevish characters, disrupts conventions ...

No progression -- Michael Worton

Beckett stressed that 'the early success of Waiting for Godot was based on a fundamental misunderstanding, that critics and public alike insisted on interpreting in allegorical or symbolic terms a play which was striving all the time to avoid definition'.

Instead of following the tradition which demands that a play have an exposition, a climax and a denouement, Beckett's plays have a cyclical structure which might indeed be better described as a diminishing spiral. They present images of entropy in which the world and the people in it are slowly but inexorably running down. In this spiral descending towards a final closure that can never be found in the Beckettian universe, the characters take refuge in repetition, repeating their own actions and words - and often those of others - in order to pass the time.

Two brief extracts, YouTube:

p. 2683: Hamm: Me to play

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IbW_5_WE7hg (4.38 mins)

p. 2687: Hamm: A few words . . . from your heart

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXKIGquILkg (1.04 mins)

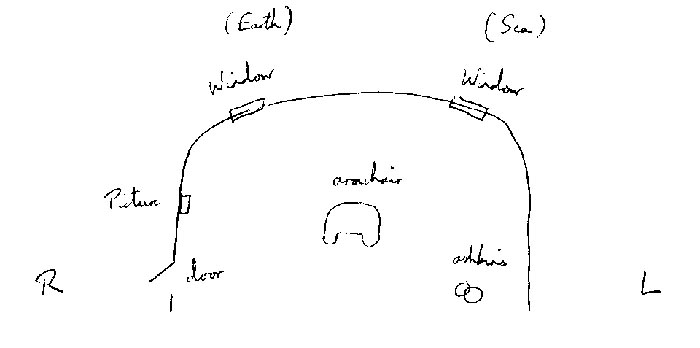

Stage set (Norton, 2662): diagram; said to represent interior of skull -- two eyes, etc.

Themes:

|

Chess "Endgame": Hamm, "Me to play" (2663, 2683, 2687) |

Post-holocaust (Nevil Shute, On the Beach 1957) Setting: The shelter (2663; 2684) |

|

Acting, Stagy: Hamm (as bad actor) Hamm: "Can there by misery …": measuring suffering, cf. Lear (2663) |

Time Grain upon grain… (2663; 2684) > i.e., moment after moment; atomizing

of time |

Body: numerous references to -- smell, eating; Hamm must sit; Clov must stand

Language: Have you not had enough? -- meaning escapes (2664)

Rationality: all we have? -- but absurd: measuring (2670; 2678); infinity (2663)

Play ends as it began (2688); could be circular -- repeated ad infinitum

Postmodern? Final meaning? -- that it cannot be made to mean any single thing. According to Wilcher (1976), the play is a comment on "the inadequacy of approaching reality by trying to impose systems upon the minute-by-minute flux of sense impressions."

Chess. "Hamm is a king in this chess game lost from the start. From the start he knows he is making loud senseless moves. That he will make no progress at all with the gaff. Now at the last he makes a few senseless moves as only a bad player would. A good one would have given up long ago. He is only trying to delay the inevitable end. Each of his gestures is one of the last useless moves which puts off the end. He is a bad player." (Beckett, cited in Worton)

---- "It is because mankind is less than omniscient that Beckett wins his chess game against the audience; and it is because the play's characters are (ostensibly) mortal that they are fated to lose their game against death." (Acheson 189)

Acting. "Although Hamm appears to be proceeding rather self-consciously through the experience of dying, Beckett keeps the spectators of this play uncertain as to whether Hamm is dying or imitating the action of dying. Hamm performs himself in a theatrical presentation of himself for himself. Clov, Nagg and Nell provide the necessary audience and, at times, assume the roles that Hamm's performance demands." (Lyons 59)

Creation. "Beckett plays with the imagery of creation from Genesis, but he reverses the sequence. He begins with a world which divides light and darkness and separates land and water and moves toward obscure greyness and void." (Lyons 62-3)

Form. The pauses in these plays are crucial. They enable Beckett to present silences of inadequacy, when characters cannot find the words they need; silences of repression, when they are struck dumb by the attitude of their interlocutor or by their sense that they might be breaking a social taboo; and silences of anticipation, when they await the response of the other which will give them a temporary sense of existence. Furthermore, such pauses leave the reader-spectator space and time to explore the blank spaces between the words and thus to intervene creatively -- and individually -- in the establishment of the play's meaning. This strategy of studding a text with pauses or gaps poses the problem of elitism, but above all it fragments the text, making it a series of discrete speeches and episodes rather than the seamless presentation of a dominant idea. Beckett writes chaos into his highly structured plays not by imposing his own vision but by demanding that they be seen or -- especially -- read by receivers who realize both that the form is important and that this very form is suspect. One of his most quoted statements, made to Harold Hobson in 1956, is as revelatory in its 'scholarly mistake' as in its affirmation of a love of formal harmony:

I take no sides. I am interested in the shape of ideas even if I do not believe them. There is a wonderful sentence in Augustine, I wish I could remember the Latin. It is even finer in Latin than in English. 'Do not despair; one of the thieves was saved. Do not presume: one of the thieves was damned.' That sentence has a wonderful shape. It is the shape that matters. (Worton)

James Acheson, "Chess with the Audience: Samuel Beckett's Endgame." Critical Essays on Samuel Beckett, Ed. Patrick A. McCarthy. Boston: H. K. Hall. pp. 181-192.

Charles R. Lyons, Samuel Beckett. London: Macmillan, 1983.

Robert Wilcher, "'What's It Meant to Mean?' An Approach to Beckett's Theatre." Critical Quarterly 18 (1976): 21.

Michael Worton, "Waiting for Godot and Endgame: Theatre as Text."

Beckett resources online, see: Apmonia: A Site for Samuel Beckett