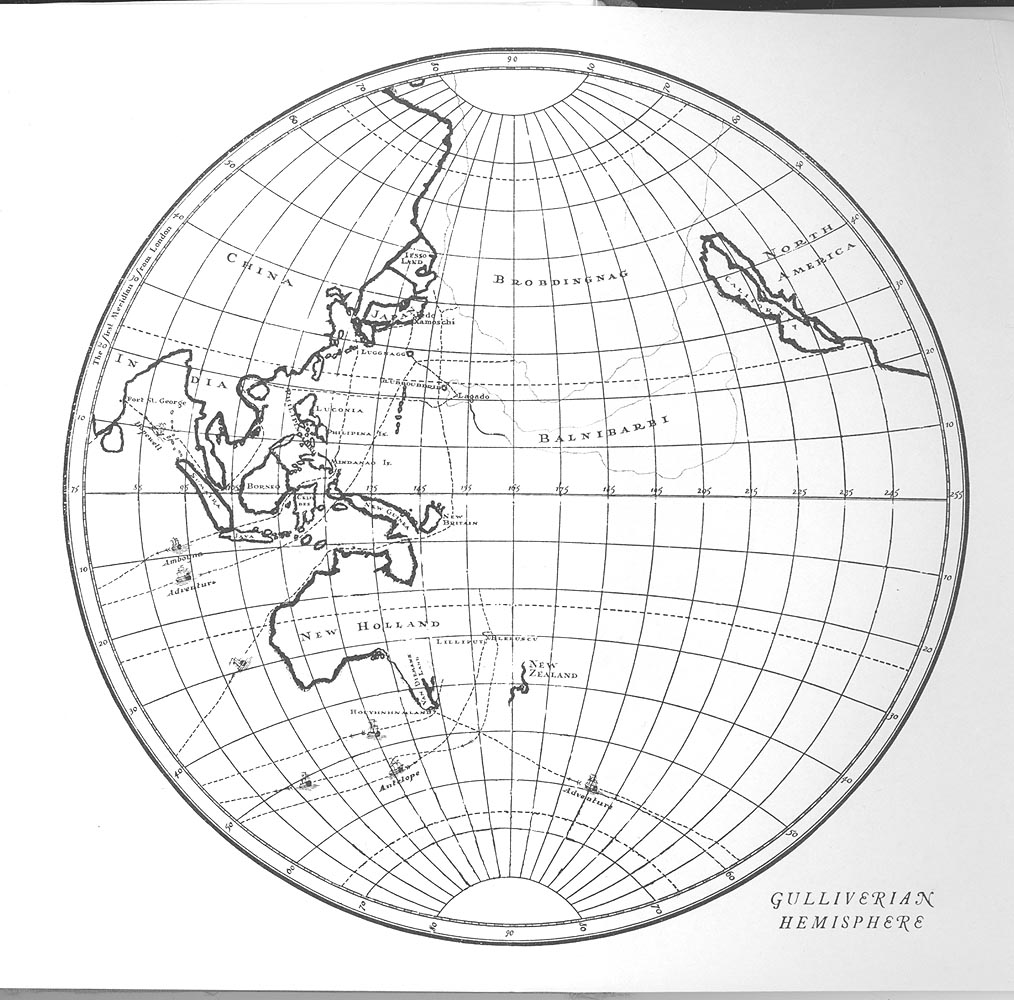

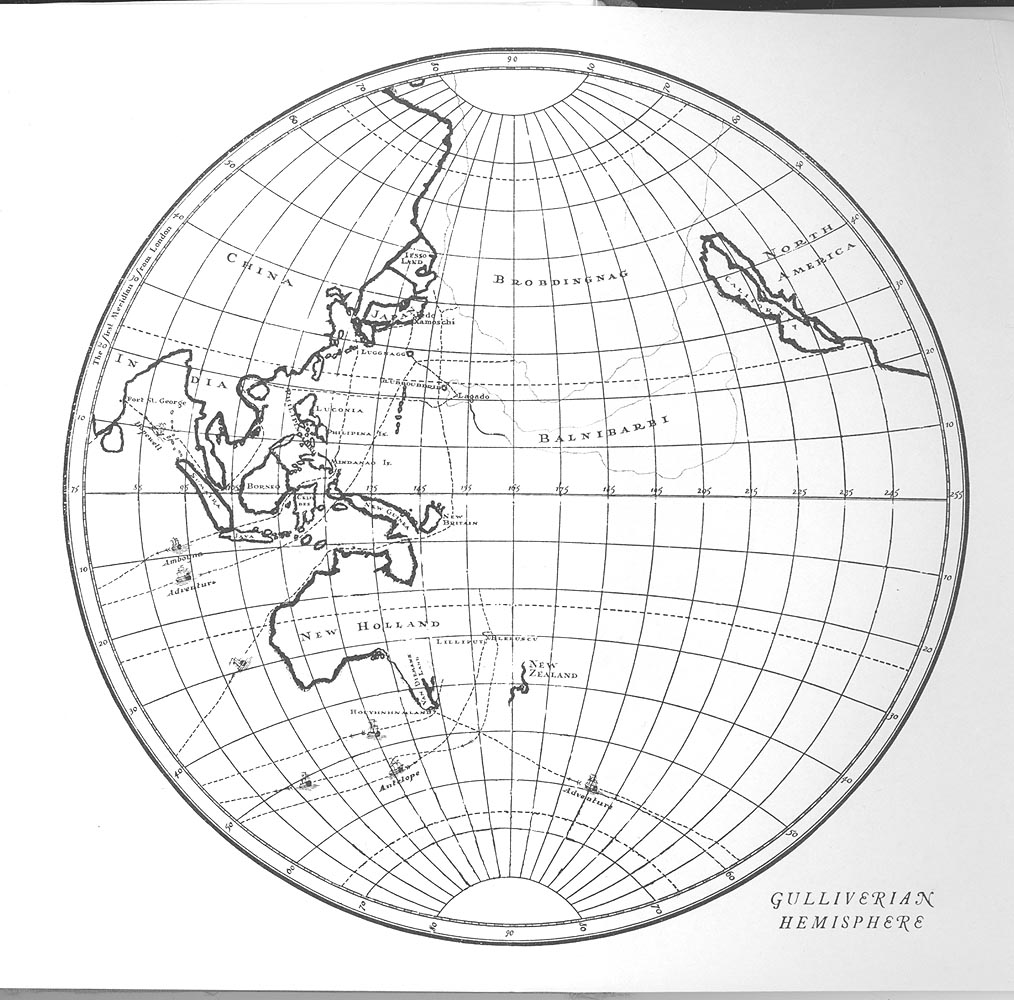

Gulliverian

Hemisphere (click to enlarge):

Gulliverian

Hemisphere (click to enlarge):Engl 112:E1

First published 1726

additional materials

1. Swift's letter to Pope (September 29 1725). Cited from Frank Brady, Ed., Twentieth Century Interpretations of Gulliver's Travels (1968), p. 3.

The chief end I propose to myself in all my labours is to vex the world rather than divert it . . . I have ever hated all nations, professions, and communities, and all my love is toward individuals: for instance, I hate the tribe of lawyers, but I love Counseller Such-a-one, Judge Such-a-one: for so with physicians (I will not speak of my own trade), soldiers, English, Scotch, French, and the rest. But principally I hate and detest that animal called man, although I heartily love John, Peter, Thomas, and so forth. This is the system upon which I have governed myself many years (but do not tell) and so I shall go on till I have done with them. I have got materials towards a treatise, proving the falsity of that definition animal rationale, and to show it should be only rationis capax. Upon this great foundation of misanthropy (though not Timon's manner), the whole building of my Travels is erected; and I never will have peace of mind till all honest men are of my opinion. By consequence you are to embrace it immediately, and procure that all who deserve my esteem may do so too. The matter is so clear that it will admit little dispute; may, I will hold a hundred pounds that you and I agree on the point.

2. Geography

Gulliverian

Hemisphere (click to enlarge):

Gulliverian

Hemisphere (click to enlarge):

Reproduced from Arthur E. Case, Four Essays on Gulliver's Travels (1958), facing p. 54.

3. Satire

Following extracts are from Northrop Frye, The Anatomy of Criticism (1970), pp. 223-4.

The chief distinction between irony and satire is that satire is militant irony: its moral norms are relatively clear, and it assumes standards against which the grotesque and absurd are measured. . . . Irony is consistent both with complete realism of content and with the suppression of attitude on the part of the author. Satire demands at least a token fantasy, a content which the reader recognizes as grotesque, and at least an implicit moral standard, the latter being essential in a militant attitude to experience. Some phenomena, such as the ravages of disease, may be called grotesque, but to make fun of them would not be very effective satire. The satirist has to select his absurdities, and the act of selection is a moral act. . . .

Hence satire is irony which is structurally close to the comic: the comic struggle of two societies, one normal and the other absurd, is reflected in its double focus of morality and fantasy. . . . Two things, then, are essential to satire; one is wit or humor founded on fantasy or a sense of the grotesque or absurd, the other is an object of attack.

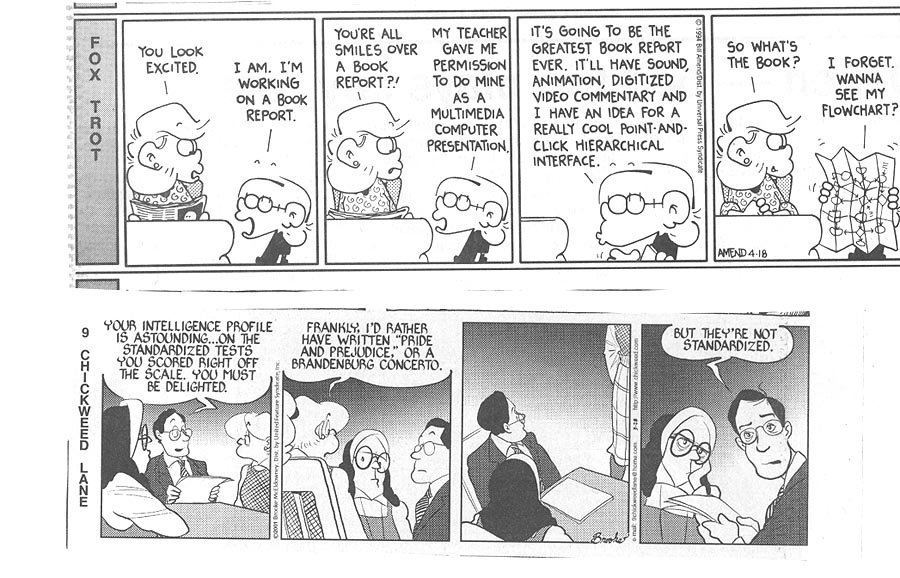

Comic strips (click to enlarge):

Not just comic: satire, implying a norm.

Document created October 29th 2006