The MennonitesDefinitionThe Mennonites are a group of Anabaptist denominations based on the teachings and tradition of Menno Simons. They are one of the peace churches, which hold to a doctrine of non-violence and pacifism. Their core beliefs, deriving from Anabaptist traditions are: 1. Baptism of believers is understood as threefold: Baptism by the spirit (internal change of heart), baptism by water (public demonstration of witness), and baptism by blood (martyrdom and asceticism). 2. Church discipline is understood as threefold: Confession of Sins, Absolution of Sin, and Re-admission of Sinner in the church. 3. The Lord's Supper as Memorial, shared by baptized believers within the discipline of the church. Mennonites strive to live the meaning of the Bible as advice on how to conduct one's life rather than viewing their faith as mere theory. [1] The 1896 statement of "Our Common Confession" states: The Conference recognizes and acknowledges the Sacred Scriptures of the Old and New Testament as the Word of God and as the only and infallible rule of faith and life; for "other foundation can no man lay than that is laid which is Jesus Christ." 1 Corinthians 3:11 In the matter of faith it is therefore required of the congregations which unite with the Conference that, accepting the above confession, they hold fast to the doctrine of salvation by grace through faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, baptism on confession of faith, the avoidance of oaths, the Biblical doctrine of non-resistance, and the practice of a Scriptural church discipline. [2] During the sixteenth century, the Mennonites and other Anabaptists were relentlessly persecuted. By the seventeenth century, some of them joined the state church in the Netherlands and persuaded the authorities to relent in their attacks. The Mennonites outside the state church were divided on whether to remain in communion with their brothers within the state church, and this led to a split. Those against remaining in communion with them became known as the Amish, after their founder Jacob Amman. Those who remained in communion with them retained the name Mennonite. Other disagreements over the years have led to other splits; sometimes the reasons were theological, sometimes practical, sometimes geographical. Mennonites in Canada and other countries typically have independent denominations due to the practical considerations of distance and, in some cases, language. There are more than 20 different Mennonite groupings that are distinguished by a wide range of life styles and religious practices. Some Mennonite communities conscientiously reject the use of modern technology, such as electricity or motor transport. Such Mennonites are often referred to as Old Order Mennonites (although the term strictly refers to a particular church within that group) in order to distinguish them from Mennonite denominations that fully accept modern inventions. Some groups have retained their original German dialect, i.e., Plautdietsch. Mennonites are prominent among denominations in disaster relief, often being the first to arrive with aid after hurricanes, floods and other disasters. There are about one million Mennonites worldwide, most of them in the United States and Canada. Settlement in Eastern EuropeBecause of persecution in their home countries, Anabaptists often had to migrate as the only means of survival. As early as 1530, Dutch-North German Anabaptists—among them Menno Simons—migrated to the Vistula Delta in what is today Poland, and from there the Mennonites moved up along the Vistula River, in time even into Poland. Until the middle of the 18th century, the surplus population was absorbed in new settlements along the river. But these migrations had been relatively small-scale. When Catherine the Great issued her Manifesto in 1763 inviting farmers from Western countries to settle in the Ukraine, the Mennonites of Prussia and Danzig were soon attracted, because they were continually encountering restrictions in their economic and religious life. Later the matter of exemption from military service became important. The approximate number that emigrated to Russia in 1787-1870 was 1,907 families, with a total of some 8,000 persons. This constituted a true mass migration of Mennonites in comparison with previous movements. Of this number about 400 families settled at Chortitza, some 1,049 at Molotschna, some 438 at Samara, and 20 families were reported to have gone to Vilna. [3]

Map of the Russian Mennonite colonies in 1875. Source: http://home.ica.net/~walterunger/S-Russia.htm Some of the Swiss-South German Mennonites—after having being expelled from Switzerland and the Alsace—went to Galicia in 1784-85, and some later to Volhynia. Emigration from Central and Eastern EuropeWhen the Mennonites in Russia and Prussia felt that they were losing their exemption from military service again and encountered economic restrictions, some 18,000 of them left Russia to settle in the United States and Canada. Although the Chortitza settlement (Old Colony) was much smaller than the Molotschna settlement, it furnished almost half of the emigrants; they were unwilling to accept a compulsory alternative service program and objected to the Russification inaugurated by the Russian government. Only few Prussian Mennonites joined this migration whereas all the Swiss Volhynian Mennonites of Polish Russia joined; half the Swiss Galician Mennonites came to America, and many of the Low German Mennonites of Poland came to the United States as congregations. An even larger migration of Mennonites from Russia occurred after World War I when in 1922-30 some 25,000 Mennonites went to Canada (21,000), Mexico, Brazil, and Paraguay. The reasons for this mass migration were the threat of complete disintegration of the religious, cultural, and economic way of life of the Mennonites. A much larger number would have escaped, had not the Second World War intervened. During the German occupation of Ukraine in 1941-43 some 35,000 were evacuated by the German army to be resettled in the Vistula area (Warthegau) where they had come from some 150 years ago. Because of the outcome of the war, nearly two thirds were forcibly repatriated by the Russian army in 1945-46, while some 12,000 found their way to Canada and South America. All the Mennonites of Prussia and Poland fled in 1945 when the Russian army approached. A large number of the Danzig and Prussian and some of the Galician Mennonites migrated to Uruguay and Canada between 1948 and 1952. Settlement in AlbertaOf the early Mennonite immigrants, few came to Alberta directly. The first major group of Mennonite settlers originated in Ontario. In 1893, Jacob Y. Shantz of Berlin, Ontario (Kitchener) selected Didsbury, 80 km north of Calgary, as a suitable location for a new Mennonite settlement, and in the following year 34 Waterloo County residents established a colony in the area. In April 1901, Mennonite settlers of "Old" Mennonite Church background from Waterloo County settled nearby in the Carstairs-Didsbury area. Other settlers came from northern Iowa, Indiana, and Michigan.

After 1910, Mennonite churches were established by settlers from Iowa and Nebraska near Tofield. The Duchess Mennonite Church, 160 km east of Calgary, was established by settlers from eastern Pennsylvania. The majority of the settlers, however, came to the Didsbury area after World War I as part of the Mennonite migration from the Soviet Union in 1922-27. Other Mennonite groups settled in Coaldale, Linden, and Rosedale. In 1932, Old Colony Mennonites left Saskatchewan to found a new colony in the Peace River area. The settlement at La Crete grew to a membership of 130 by 1950, with additions of dissatisfied families coming from Mexico. Re-migration from Mexico and Bolivia brought Mennonites to northern and southern Alberta in the 1990s. The total Mennonite population of Alberta in 2001 was 22,785. Ten years later, the Mennonites numbered 24,550 persons. In 2001, almost one quarter of the Mennonites lived in the cities like Calgary (3,590) and Edmonton (1,525), but were otherwise spread out over the entire province. Large numbers of mostly conservative Mennonites have settled in the north of the province near Fort Vermilion and La Crete and in the Grande Prairie region near the Alberta-B.C. border. Based on 2001 Census data, of the 22,790 Mennonites 3,085 were immigrants. 800 Mennonites had arrived in Alberta before 1961; between 1971 and 1980 another 215 immigrated, in the following decade 370; between 1981 and 1990 645 Mennonites came to the province, and 1,055 between 1991 and 2001. According to newspaper re-ports, as many as a thousand Mennonites came to La Crete in northern Alberta from drought-stricken Bolivia in 2001. The 2011 National Household Survey reported that of the 24,450 Mennonites 1,375 arrived between 2001 and 2005 and a further 1,215 between 2006 and 2011. Because the NHS did not report on all localities, but only cen-sus metropolitan areas and census agglomerations, it is difficult to tell where the immigrants went. Of those listed in the survey 245 came to the Lethbridge CA between 2001 and 2011, and 50 to the Medicine Hat CA; another 90 arrived in Calgary, Edmonton, Okotoks and Camrose CMAs in the same time period. This leaves 2,200 Mennonites who came to Alberta in that decade unaccounted for by this table focussing only on the larger centers and ignoring the rural areas. It should also be remembered that among the 18,890 non-immigrants many will have resided in Alberta for a long time, while others who had emigrated to Central and South America and never gave up their Canadian citizenship were not counted as immigrants.

East of Edmonton, Mennonites live in towns such as Tofield and Stettler, and in central Alberta there are large numbers of Mennonites in towns and villages such as Beiseker, Didsbury, and Linden. Other localities with large concentrations of Mennonites can be found in southwestern Alberta (e.g., in Lethbridge, Pincher Creek, Coaldale, Taber, and north to Vauxhall) and southeastern Alberta (Medicine Hat and north to Duchess, Rosemary, and Gem). Many Mennonites in

Alberta still speak German, but not all, of course, do: In the 1991 Census,

10,145 Mennonites of the ca. 22,000 Mennonites in Alberta—less than half!—said

that they had acquired German as their mother tongue. As a matter of fact, in

the traditionally Mennonites localities, such as Coaldale, Hanna, Tofield, and

Linden, no children were reported by the Census to grow up with German as their

mother tongue, and there were no children in these places who were learning

German as their home language.

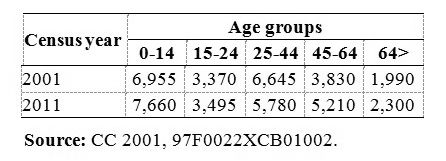

Conservative Mennonites tend to have large families: According to the 2001 Census, almost one third of Alberta's Mennonites were children below the age of 15; another 15% ranged in age between 15 and 24. Considering the fact that many Mennonites in Alberta's north still acquire German as their mother tongue, the chances are good that these children are growing up with German as their home language.

Notes[1] "Mennonitism," http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mennonitism. Accessed on March 8, 2004. [2] Canadian Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, "Our common confession," http://www.mhsc.ca/encyclopedia/contents/o9.html. Accessed on March 10, 2004. [3] Canadian Mennonite Online Encyclopedia, "Migrations," http://www.mhsc.ca/encyclopedia/contents/m542me.html. SourcesThis section is based, to a large extent, on the following sources: 1. "A People on the Move: Germans in Russia and in the Former Soviet Union: 1763 - 1997," https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/history_culture/history/people.html. Accessed on August 29, 2016. 2. Canadian Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, "Migrations." http://www.mhsc.ca/encyclopedia/contents/M542ME.html. Accessed on February 12, 2004; "Alberta." http://www.mhsc.ca/encyclopedia/contents/A434ME.html. 3. Manfred Prokop, German Language Maintenance across Canada (Edmonton: 2004). |