Writing Competitions as a New Research Method

Raija Warkentin

Raija Warkentin, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario

Abstract:

The goal of this article is to introduce the international audience to writing competitions as a data collection method. Although commonly used in Finland this method is less known elsewhere. The article will use a Canada-wide writing competition on the Finnish-Canadian sauna as an example of this method. It compares and contrasts the method to two other more commonly used methods, interviewing and auto-ethnography. The advantages, disadvantages and challenges of this method are described and discussed. According to the author, a writing competition is a fast way of gathering a large amount of data from a wide geographical area.

Keywords: data collection, writing competition, interview, autoethnography, qualitative methods

Acknowledgments: An earlier draft of this article entitled "Studying the Finnish sauna by three methods" was read at the Advances in Qualitative Methods International Conference in Sun City, South Africa January 23-25, 2002. Part of this study was financed by the SSHRC Aid to Small Universities Grant, which I shared with Dr. Patricia Jasen. Other portions of this project were made possible by the help of a grant from the SSHRC Research Development Fund and the Senate Research Committee of Lakehead University. I wish to thank Dr. Kaarina Kailo for her collaboration on part of this project. I am thankful to the Thunder Bay Finnish-Canadian Historical Society and Finnish Literature Society for their sponsorship of the writing competition. I wish to thank all the individual businesses and associations in Thunder Bay, Toronto, Sudbury, and Finland, who generously donated prizes to the winners of the writing competition. I am grateful to Gillian Smith for her participation in one interview, her editorial help, and comments on the first draft of this paper. Finally, I thank the three anonymous reviewers for their scrupulous reading of my submission, valuable suggestions, and comments.

Citation information:

Warkentin, R. (2002). Writing competitions as a new research method. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1 (4), Article 2. Retrieved DATE from http://www.ualberta.ca/~ijqm/

In Finland, researchers in collaboration with staff of archives commonly use a writing competition as a method of data collection. For instance, since 1926 the Finnish Literature Society has routinely gathered folklore through writing competitions. By this method, it has collected narratives about various occupations and groups including construction work, engineers, farmers, loggers, plumbers, police officers, refugees, shoemakers and tailors, soldiers, and impaired people. It has narratives about hospitals, post offices, forest sales, alcohol consumption, and courts of justice (for a detailed listing of these archives, see Finnish Literature Society, 1999). It has also organized several life history writing competitions, for specific categories such as women, men, art fans, civil servants, and people from various cultural regions of the country. Numerous masters students (e.g., Puromies, 1999, in folklore) and doctoral students (e.g., Peltonen, 1996, in history) have written their theses based on the data such competitions have produced. Researchers of cultural traditions, historians, sociologists, political scientists, educationists and so on analyse the material collected by writing competition (J. Nirkko, personal communication, August 16, 2002). The Finnish Literature Society now houses one of the largest collections in the world of oral and written material about Finnish traditions and culture comprising 515 shelf meters of manuscript notes, 14,500 hours of sound recordings, 950 hours of video recordings, and 110,000 photographs (as of 1997) (Finnish Literature Society, n.d.).

My purpose with this article is to introduce writing competitions as a research method to the international audience because it is little known outside Finland. I will refer to examples of the Finnish Literature Society and to a writing competition I helped organize in Canada while studying the Finnish-Canadian sauna. Although I am from Finland and, as a student of folklore did a practicum1 in the archive of the Finnish Literature Society, it did not occur to me to use this method for my own research. It was my colleague Kaarina Kailo who initiated the use of this method in Canada on our mutual project referred to above. In this article, I examine the various steps in organizing the competition and the data processing. I will then compare the writing competition with two more conventional methods of data collection, namely interviewing and auto-ethnography. Some challenges and advantages of this method are also evaluated.

All the examples in this article refer to the sauna, which is an important aspect of Finnish culture. Although saunas were commonly used all over Europe in the Middle Ages, they have disappeared in most of the countries. Finland, however, has retained its sauna tradition until today. Although it is not agreed that Finns invented it, the sauna can be considered as important to Finns as wine is to the French (Vuorenjuuri, 1967). In the late 1990s, there were 5.1 million people in Finland and 1.7 million saunas (Helamaa, 1999), which means that there is one sauna to every three people in Finland. Through migration, the sauna has spread all over the world, where it has become a symbol of Finnish ethnicity (Heinonen & Harvey, 2000; Jordan and Kaups, 1989; Lockwood, 1977; and Stoller, 1996).

For research purposes, a writing competition is organized to attract a large number of entries about a certain topic. Obviously, the topic itself must interest the target population, and the target population be large enough to elicit a sufficient number of entries. The first challenge was how to disseminate information about the competition in such a large country as Canada. National and local newspapers, ethnic papers and clubs, television and radio, and the Internet were all possible venues for advertising.

In the sauna project, we announced the competition in the fall of 1999 (see Appendix 1). We mentioned in the announcement that the writers were free to write on any aspect of the sauna but we asked many questions in order to inspire the writers to think of the subject matter from various perspectives. Also, we suggested that writers use a pseudonym to ensure an unbiased evaluation by the judges, and place their real names in separate envelopes that would be opened after judging was complete. I then sent the announcement to all the Finnish-Canadian associations across the country, having obtained the details of these from various Finnish-Canadian newspapers. I issued a press release to the Finnish-Canadian newspapers and two local newspapers (the Chronicle Journal and the Green Mantle), and to the Finnish Embassy in Ottawa. I also placed notices at several Finnish-owned businesses in Thunder Bay, Ontario and on the bulletin boards all over the Lakehead University campus.

We were fortunate in that some of the media and the Embassy were quite willing to help us. The Embassy and Finland’s Bridge (a magazine) both placed the announcement on their websites. The Toronto Star (a daily newspaper with a large circulation throughout Ontario) picked up the press release, following which the announcement spread to newspapers nationwide.2 Both the CBQ (regional) and the CBC (national) radio networks phoned me for several interviews.3 However, once the press release was out and the interviews completed, I had no control over what was written or broadcast. Therefore, the instructions that writers received were not always uniform, and because some never saw our complete announcement, they could not follow the instructions properly.

I asked the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society to lend their name as the sponsor of the competition. The Society was pleased to agree and offered their archive as the repository of the collected materials. The Society paid for our postage, contributed towards the cost of the award ceremony in Toronto and gave a few prizes. Later, the Finnish Literature Society requested a copy of the entries for their folklore collection in exchange for the donation of ten prizes of books.

As the entries arrived, I kept a log of the senders, their postal and email addresses, and telephone numbers, which proved to be a difficult task to keep updated.4 I wrote down the title of each entry, the number of photographs sent and whether the photographs should be returned. I also recorded the number of pages of each entry. This turned out to be important information, as entries came in various formats; some entrants used odd sized paper or wrote on both sides of the paper and I feared it would be easy to lose track of the entries. I lost one page when photocopying the entries and had to write to the entrant to ask him to resend it.

Some writers sent in their only copy and asked me to send them a copy of their entry for a keepsake, which I was happy to do. During the contest, I also received about thirty inquiries by post, email, and telephone about the competition, the award ceremony, and the subsequent publication. After the competition, I wrote letters of thanks to all participants and informed them of the prizewinners and the prizes. Thus, throughout the data collection and the period immediately following there was a considerable amount of correspondence. Additionally, when the planned book is published, I will notify all the participants.

The entries arrived from all over Canada but, of course, there was a regional variation in numbers. Some people submitted several entries and some sent information without entering the competition. Counting them as entries for the purpose of the following analysis, the collection results in a total of 133 entries comprising 387 original pages. The majority (75%) of the entries were from Ontario (and, of these, most were from Thunder Bay). The other writers were from British Columbia (14%), Alberta (4%), and Manitoba (2%). Four writers were living in the United States and one in Ireland, although they had previously lived in Canada. There were more entries from women (61%) than men (39%). English was the language of most pieces (84%), whereas Finnish was used in 16% of the entries. Some writers submitted entries in both languages.

We, as organizers, were delighted with the participation rate, which surpassed my goal of 100 entries. It was not, however, as high as participation rates for writing contests in Finland. When the Finnish Literature Society organized a writing competition on the sauna in 1992, although Finland has a population of five million, it received entries from 470 individuals and produced 3,750 pages in original manuscripts (Finnish Literature Society, 1999). The rates show that the Finnish population is more responsive to opportunities like this.

Jorma Halonen, as a representative from the Thunder Bay Historical Society, and my colleague from Finland, Kaarina Kailo, agreed to be judges with me for the writing competition. We thought that prizes would help motivate participation and it would be advantageous to mention the items for prizes in the competition announcement. The Finnish Literature Society has resources of their own for prizes. For example in the sauna writing competition in 1992, they gave three cash prizes of FIM 5,000, 3,000 and 2,000 (the equivalent of $1,250, $750, and $500 Canadian), two special prizes, and 20 books or sauna items (J. Nirkko, personal communication, August 16, 2002).

We felt it would be simplest if the researchers were able to secure an allocation for prizes in their research grant. We, however, did not have this advantage, and therefore had to solicit prizes from businesses and organizations. In our announcement, we optimistically stated, "Prizes will vary from books to items such as Finnish glass, jewelry, and T-shirts (donated by Finnish-Canadian stores and the Finnish Literary Society)" (see Appendix 1 ). Then we started our soliciting campaign. We sent letters and emails, and phoned or personally visited Finnish businesses and associations in Thunder Bay, Sudbury, Toronto, and Finland. We were eventually able to acquire the prizes as advertised except the jewelry. In addition, we received gift certificates from two Finnish bakeries, a butcher, a restaurant, a florist, a travel agent, a ski-resort owner, Finnish-Canadian newspapers, an accountant, and several law firms. We also received a monetary prize from a Finnish church in Toronto and a case of motor oil from an auto garage. When deciding how to allocate the prizes, we sometimes combined several low value gift vouchers as one prize.

We organized an award ceremony in conjunction with the Finn Grand Fest in Toronto in the summer of 2000, at which the 26 prizewinners were announced. Jorma Halonen compiled a display of the entries and photographs for the occasion. The media were informed of the event and the prizewinners were invited to attend. We mailed the prizes to those who were not able to accept them in Toronto. I wrote letters of thanks to all prize donors informing them who had received their particular prize.

We did not know beforehand what criteria to use for judging the entries but these developed on their own after reading all the entries several times. The two criteria that emerged were stylistic and informational: we also considered both of these criteria to be useful for our research. The two main categories were prose and poetry. For prose, we gave prizes in the English language category for an entry from the viewpoint of someone with roots in the sauna tradition and another one from the viewpoint of an outsider to the sauna tradition. We also gave a prize for the best Finnish language story of the sauna experience. Other prize categories for prose were for a fiction story in either language and for a childhood sauna description. In poetry, we again divided the categories according to the language and, in addition, gave a prize to the two (and only) negative views on the sauna for the sake of fairness and especially because they were well written. Finally, twelve entries received an honorable mention.

Because some writers did not mention anything about their background, not even whether they were of Finnish descent, I sent a form to all writers requesting their immigration history. This form also included a written consent to use the data in research and publications, and to place the entries in the archives mentioned above. From the immigration histories sent back, 71% of the writers were Finnish-Canadians and almost one quarter (24%) were not of Finnish heritage. We could not reach 4%, and their origins remain unknown. Half of those who were not Finnish-Canadians had Finnish relatives or neighbors whose sauna customs they had observed. The remaining 12 % claimed no connection with Finland.

To do coding and analysis of the material, we needed to have the entries in electronic form, although for the purpose of deciding the prizes, any form of manuscript was adequate. We had envisioned receiving the entries in electronic form, although this was not requested in the contest announcements. It is true that some entries were received electronically, but most of them were printed copies and had to be scanned or, in the case of 21 handwritten entries, typed into the computer. One was an audiotape that had to be transcribed. All the scanned entries needed "cleaning" because the scanning device often misinterpreted characters. This was the most labor-intensive aspect of the research process. All the entries had to be made uniform with regard to fonts, line spacing, and margins, as well as in the format of the titles and authors’ names. Lakehead University paid for part of the data processing through the Ontario Student Work Program and a Senate Research Grant. Kaarina Kailo utilized help from a student assistant in Finland. My students coded all of the material. Jorma Halonen and I translated some of the entries either into Finnish or English for the sauna book that we are presently preparing for publication.

The writing competition was not the only method by which the Finnish-Canadian sauna was studied. We had actually started investigating the health care of Finnish-Canadian women a few years earlier (in 1996) by the method of interviews.5 The interview questions (see Appendix 2) covered a wide range of topics and were not restricted to the sauna. As I was living in Thunder Bay, I interviewed women in the city and its vicinity. It became obvious that, for most interviewees, the sauna played an important part in maintaining health and providing a sense of well being (see Warkentin, in press). I interviewed 28 women, most of them individually or in groups.6 As I had to fit the interviews in with my academic work at the university, it was a very slow process, taking five years (1996-2001) to complete the interviews with 28 participants. I met with some of the women several times, although most of the women completed the whole interview at one sitting. The shortest interview lasted about one hour, with the longest one totaling 22 hours in four sittings. Only a portion of these interviews have been coded to date.

If the speed of the data collection is considered, the writing competition is by far a faster way than individual interviews. Data processing was tedious by both methods: whether it was transcribing the oral interviews or entering the handwritten or scanned entries of the competition on the computer. Of course, the individual written entries were much shorter than interviews but there were five times more writers than interviewees. Another consideration is the comparability of the data from one individual to another. In the interviews, all the women were asked the same set of questions, which made the material easier to compare than the entries of the writing competition, where the writers were encouraged to write about any aspect of the sauna they wished to consider. The writing competition was more open ended and the writers more likely to throw in ideas that the researchers had not considered.

Another consideration is naturalism, which proposes that the social world should be studied in its 'natural' state undisturbed by the researcher (e.g., Hammersley & Atkinson, 1983, p. 6; Lofland, 1967). The shortcoming of interviewing is that, of course, an interviewer's questions and even his/her unspoken interests affect what the interviewee says (Danielsen, 1995, p. 111). His/her mere presence affects the outcome and it is not always possible to know in what ways. The positive side of the interviewing is that the researcher has carefully thought of the questions, so all areas of his/her interest will be covered. It is also possible to make clarifying questions on the spot. Using my interview schedule, I received information about the entire immigrant life histories of the interviewees. In contrast, the sauna writers gave only fragmented information about their immigrant life. Their context was understandably narrower. A writing competition, however, fulfills the criterion of naturalism better than interviews in that there is less of the influence of the researcher. The writers expressed the aspects of the sauna that were meaningful to them.

Writing competitions have been criticized in Finland for possibly attracting only exceptional people or those who want attention (J. Nirkko, personal communication, August 16, 2002). I would think that it requires quite a motivation to write and submit an entry, and that it takes less initiative to answer questions of an interviewer. To be inspired to write, perhaps, does require the writers to think they have artistic talent, but also, not everyone would want a long interview and to be taped. Writers must really feel they have something to say — perhaps they feel very strongly about the sauna. It is true that writers created funny, sad, or enthusiastic accounts of the sauna, sometimes to the point of ethnocentrism. They typically saw critical outsiders in strongly negative terms. In contrast, few interviewees had faced antipathy towards their sauna use. They tended to talk about the sauna in more general terms, about its everyday use, and did not glorify it as most writers did. There was only one written entry (a poem) that expressed reasons for giving up the sauna, but there were several interviewees who said they had abandoned the habit of taking a sauna. A writing competition seemed to produce more black-and-white views on the sauna, whereas the interviews created data that are likely more realistic.

The photographs provided by interviewees in my earlier research portrayed the same principle as the interviews in that they told a story of immigrant life beyond the sauna. When I interviewed the women, I often asked for old photos of the sauna. The interviewees went through their albums and found photos. The saunas in those photos were not central. They were often part of the home complex or a logging camp; sometimes they were in the background of a group of people and often only incidentally included in the pictures (see Image 1).

|

Image 1. Hilkka Hautala found this picture of a sauna (right) in her photo album. The picture was taken at a logging camp at Aslar Bay of Edward Island (Lake Superior, Ontario), where she worked as a cook in 1968. |

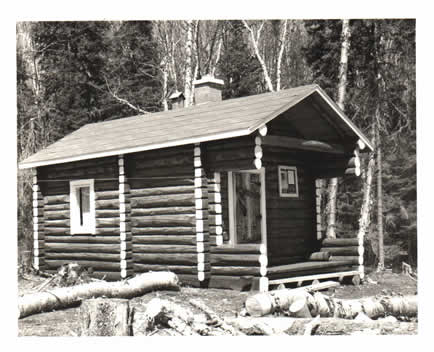

In contrast, the writers in the writing competition sent photos in which their saunas were clearly the center of attention. They were proud of their saunas, which they had built with their own hands (see Image 2). Other photos showed them heating the sauna, making the birch twigs for their sauna, posing in front of their sauna with friends, and so on. There were also drawings of the sauna: romantic ones of the old fashioned smoke sauna, or a blueprint of the writer's sauna. Again, it seems that the writers had an emotional attachment to their saunas.

|

| Image 2. Yrjö Rouhiainen proudly sent this picture of a sauna to the sauna writing competition. He built his first sauna "with his own hands" at Jackfish Lake, Ontario, in 1958. |

I have not written an auto-ethnography of my sauna experiences in the same way as Ellis (1995), for example, has written about her experience of chronic illness. I am, however, an insider to the sauna culture because I was born and raised in Finland. A researcher cannot understand the Finnish sauna culture without experiencing the sauna, or doing some sort of auto-ethnography. One has to experience the damp heat, the scents, the dim light, the change in temperatures, the fellowship, and the ritual of the sauna to make sense of Finns' descriptions of their saunas. While doing research I had to reflect on my own sauna experiences.7 I recalled my childhood and clarified my current attitudes toward the sauna. Coincidentally, my long-awaited sauna-building project occurred at the time of the writing competition. Thus, I was not an objective observer but deeply embedded in the sauna topic.

It seems to me that inside knowledge of the sauna culture is simultaneously an asset and a handicap. It provides a deep insight into, and understanding of, the topic, but at the same time it biases me against outsiders. I understand the ritual meaning of the sauna and I share many of the writers' enjoyable experiences of the sauna. I was also able to understand those writers who described ostracism or ridicule by non-Finns because of their sauna customs. I readily empathized with Susan Vickberg, a competition entrant, when she wrote about her devastating experience at school. When she proudly gave a presentation to her class about her family sauna, she was sent to the principal's office and her mother was summoned from home. After the ordeal, the mother told Susan, " 'It is best that we do not speak of these Finnish ways of ours. It just gets us into trouble in this Canada land.' Consequently, for many, many years I spoke no more of my being Finnish" (Vickberg ms, p. 14). During the writing competition, I experienced negative attitudes by some Canadians and empathized with this entry.

This kind of understanding and empathy, however, implies a lack of ethnographic distance that Brower, Abolafia, and Carr (2000) call on from researchers. I was caught up with an ethnocentric view of the sauna and had little sympathy for those outsiders who did not appreciate it. I was unaware of this attitude until a colleague and friend8 made me aware of it when I was writing an article on the misconceptions of the sauna (Warkentin, 2002). After all, I as an anthropologist, who has experienced culture shock both in Africa and in Canada, should understand that it is not all that easy for the outsiders to understand why we Finns go crazy about our saunas! After many years in Africa studying the "other", in Canada I had become the"other". In the future, it would be useful for me to analyze the sauna with somebody who is outside the culture. That way some more distance would be gained.

The three approaches — the writing competition, interviews, and auto-ethnography method — gave partly overlapping and partly different information about the sauna. It is fitting that qualitative research has been described as "bricolage": pragmatic, strategic and self-reflective (Nelson, Treichler, & Grossberg, 1992, p. 2), and a qualitative researcher as a "bricoleur" (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Lévi-Strauss, 1966, p. 17, Weinstein & Weinstein 1991, p. 161). The common term "triangulation" highlights the frequent use of multiple methods in qualitative research. In order to validate information, qualitative researchers do not repeat scientific experiments, as quantitative researchers routinely do, but we use triangulation (e.g. Denzin, 1989; Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Flick, 1992; Morse, 1991). According to Flick (1992, p. 194), multiple methods add rigor, breadth and depth to any investigation. Self-reflection is always present in all qualitative research (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994). Above, I have outlined the method of the writing competition in comparison with two other methods that I have used for the research of Finnish-Canadian saunas. I have also pointed out the practicalities of each method and the data differences they produced. This article is the start of triangulation for myself: I have written individual articles on both the writing competition and the interviews, although my personal experiences in self-reflection are inseparably tied to all analyses. This is the first time that I have compared the methods. The scope offered by gathering together these different methods will emerge in my future research projects.

The method of the writing competition is a fairly easy and fast way of data gathering in that the researcher does not need to travel to meet the participants nor take time to interview them. It takes less time to reach a far larger group of people. It involves, however, advertising the writing competition to the target group, finding sponsors, and judging the entries. There are labor-intensive parts to the writing competition such as correspondence with writers, organizing and giving out prizes, data "cleaning," processing, and coding. As people become more familiar with the use of computers and the Internet, the announcement and entries will be more commonly transmitted electronically and thus will be faster to process. Now that triangulation is promoted in qualitative research, writing competitions are a viable option.

1. In Finland, folklore is a separate discipline from anthropology. Practicum for the folklore students includes copying and organizing file entries in the archives. Back to text

2. We know this through the writers who mentioned having seen the announcement in various local newspapers. Back to text

3. CBQ broadcast with Gerald Graham (October 1,1999), and CBQ news with Shane Judge the same day. CBC Fresh Air with Jeff Goodes (October 2, 1999), and CBC As It Happens with Rick McInnis Ray, October 4, 1999. Back to text

4. Unfortunately, we lost touch with some of the writers because they did not inform us when they moved. Back to text

5. At the same time, I became acquainted to two other researchers who were interested in women's health, Dr. Patricia Jasen, a professor of history at Lakehead University, and Dr. Kaarina Kailo, at the time a professor of women’s studies at Concordia University. Although our attempts to receive further funding together failed, we were able to continue research in our respective areas. They inspired my research because our interests were similar, although we each eventually worked independently of each other (see Kailo, 1997,1999, 2000, in press). Kaarina Kailo and I are, however, collaborating with Jorma Halonen on a book entitled Sweating with Finns: Sauna stories from North America (in preparation). Back to text

6. Gillian Smith helped me with the first group interview and Kaarina Kailo collaborated with me on the second one. All interviewees signed a consent form and indicated whether they wanted to use their true name or a pseudonym. They also signed an agreement permitting their interviews to be placed in the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society archive. All interviews, except for that of the first group, who preferred not to be recorded, were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The research grant helped pay for the transcribing. (Gillian Smith made hand-written notes of the group interview that was not taped and she typed them after the interview). Back to text

7. I grew up in Finland where I was used to taking a sauna bath with my family at least once a week. When my father built a new home or cottage, the sauna was erected first. I remember walking two kilometers with my sister from my home to prepare the sauna on the building site of the new home. I was accustomed to invite friends to take the sauna bath with me. Many a time I had my classmates roll in the snow and run to warm up in our family sauna. When my English pen-friend visited Finland for the first time, she was invited to the sauna when arriving from the airport. I had learned that inviting a guest to the sauna was the "true" hospitality. There were extra saunas for Christmas, Easter and Mid-Summer. Sauna was also heated to relax muscles after strenuous ski trips. I thought that nothing would match the sauna for attaining comfort and cleanliness. When I moved to Zaire, Africa, for ten years, I missed the sauna. When talking about building one there I encountered surprised looks. My African and American friends didn't share the same desire, which in turn surprised me, because I thought all people would appreciate the sauna once it had been explained to them. Later, when I moved to Canada and reminisced about the sauna of my childhood home, my in-laws were surprised, perhaps even a bit morally annoyed to see my enthusiasm for nude bathing. It was only then that the possibility dawned on me that some people did not wish to know about the Finnish sauna. When my husband and I finally had a chance to have a sauna built on a lakeside lot in Canada, I was happy to resume my interrupted sauna practice, only to experience a very negative reaction from some Canadians. They did not appreciate the smoke rising from the sauna chimney even though they frequently had smoky bonfires themselves. Our smoke was offensive to them and was a symbol of backwardness. They inquired if I understood English, if I had a visa to stay in the country, and asked me to go back to the country I came from. They made remarks about my nude bathing and they built a high woodpile to block their view of the undesirable sauna. What was commonly acceptable in Finland was offensive to some in Canada. Back to text

8. I am grateful to Gillian Smith for pointing out my ethnocentrism. Back to text

Brower, R. S., Abolafia, M. Y., & Carr, J. B. (2000). On improving qualitative methods in public administration research. Administration & Society,21(4), 363-380.

Danielsen, K. (1995). Livshistorier — fakta eller fiction? [Life histories: Fact or fiction?]. Norsk Antropologisk Tidskrift, 6, 105-115.

Denzin, N. K. (1989). The research act. (3rd edition) Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall.

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Introduction. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1-17). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ellis, C. (1995). Final negotiations: a story of love, loss, and chronic illness. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Finnish Literature Society. (n.d.) The Folklore Archives of the Finnish Literature Society. Retrieved October 25, 2002 from http://www.finlit.fi/english/eng-folk.htm.

Finnish Literature Society. (1999). Kansanrunousarkiston keruukilpailut [The writing competitions of the folklore archives]. Retrieved October 25, 2002 from http://www.finlit.fi/kra/kokoelma/kilvat.htm.

Flick, U. (1992). Triangulation revisited: Strategy of validation or alternative? Journal of the Theory of Social Behavior, 22, 175-198.

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (1983). Ethnography: Principles in practice. New York: Tavistock Publications.

Heinonen, T., & Hussa Harvey, C. (2000). Finns of Manitoba: Stories of immigration, settlement and integration. Unpublished paper.

Helamaa, E. (1999). Saunan ja kiukaan historiaa [Some history of the sauna and sauna stove]. In Juha Pentikäinen (Ed.), Löylyn henki: kolmen mantereen kylvyt (inipi, furo, sauna) (pp.114-123). Helsinki: Rakennustieto Oy.

Jordan, T., & Kaups, M. (1989). The American backwoods frontier: An ethnic and ecological interpretation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kailo, K. (1997). Beyond the clinical couch and the patriarchal gaze: Healing abuse in the Finnish sauna and through holistic sweats. Simone de Beauvoir Institute Review/Revue de l’Institut Simone de Beauvoir, 17, 89-114.

Kailo, K. (1999, July 23). Affinities between Finns and native people: Rebirth rituals and the sweat tradition of Finns and Native peoples. Vapaa sana, 3.

Kailo, K. (2000). Suomalainen sauna ja intiaanien hikimaja uudelleensyntymisen kohtuna [The Finnish sauna and the native sweat lodge as a womb of rebirth]. Sauna, 4, 8-13.

Kailo, K. (in press). Baring our being: Sauna and sweatlodge as ritual spaces. In E. Conradi (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Sauna Congress May 1999, Aachen, Germany. Deutsche sauna bunde.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lockwood, Y. (1977). The Sauna: An expression of Finnish-American identity. Western Folklore, 36 (1), 71-84.

Lofland, J. (1967). Notes on naturalism. Kansas Journal of Sociology, 3(2), 45-61.

Morse, J. M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nursing Research, 40, 120-123.

Nelson, C., Treichler, P. A. & Grossberg , L. (1992). Cultural studies. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson, & P. A. Treichler (Eds.), Cultural studies (pp.1-16). New York: Routledge.

Peltonen, U. 1996. Punakapinan muistot. Tutkimus työväen muistelukerronnan muotoutumisesta vuoden 1918 jälkeen. [Memories of the Red rebellion. Research on the evolution of the tales of the laborers after1918]. Helsinki: SKS.

Puromies, L. (1999). Ihmisiä saunomisen tilassa: elämyksiä saunassa ja saunan merkityksiä. Kulttuurianalyysi yhden perinteen keruukilpailun tuloksista. [People in the state of saunaing: sauna experiences and meanings of the sauna.] Unpublished masters thesis. Department of Cultural Studies, Folkloristics, Helsinki University, Helsinki, Finland.

Stoller, E. P. (1996). Sauna, sisu and Sibelius: Ethnic identity among Finnish Americans. The Sociological Quarterly, 37(1), 145-175.

Vuorenjuuri, M. (1967). Sauna kautta aikojen [The sauna through the ages]. Helsinki: Otava.

Warkentin, R. (2002). Unorthodoxies and misconceptions of the sauna in Canada. In O. Koivukangas (Ed.), Entering multiculturalism: Finnish experience abroad. Turku, Finland: Institute of Migration.

Warkentin, R. (in press). Use of the sauna among Finnish-Canadian women in a Northern Canadian city: Preliminary research report. In E. Conradi (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Sauna Congress May 1999, Aachen, Germany. Deutsche sauna bunde.

Weinstein, D., & Weinstein, M.A. (1991). Georg Simmel: Sociological flaneur bricoleur. Theory, Culture & Society, 8, 151-168.

ANNOUNCING A WRITING COMPETITION ON THE FINNISH CANADIAN SAUNA

Everyone who has Finnish neighbors knows that they are enthusiastic about the sauna. A writing competition has been announced on the use of sauna by both Finns and non-Finns. Sauna customs, traditions, experiences, rituals and beliefs concerning the sauna are being sought with the purpose of preserving this knowledge in the archives for future generations.

What is it about?

Researchers Raija Warkentin and Kaarina Kailo in collaboration with the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society are looking for relevant explanations, poems, short stories, autobiographical sketches, memoirs and essays on Finnish Canadian experiences of the sauna which would throw light on the present state of the Finnish sauna culture in North America. Non-Finns are also invited to participate. We are interested in answers to the following kinds of questions:

More topics:

In Finland the sauna was used for various purposes such as for rituals in times of transition in an individual's life: birth, marriage, and death. Also special magic was practiced in the sauna in order to evoke love in another person. These customs are worth writing about if anyone can remember them. Also, special healing ceremonies were practiced in the sauna for ailments and diseases, depression, a broken heart, violence, sexual abuse and so forth. The researchers would like to know if any of these are still remembered and practiced among Finnish-Canadians. Has anyone seen cupping or bloodletting in the sauna, which was common in the old days? The Finns in Finland like to "beat" themselves with birch whisks in the sauna. In Canada birch is not always available and it would be nice to know what else may be used. Also, the old Finns used honey and tar in the sauna. Are these being used, or have some other ointments replaced them? Can women and men endure the steam equally? The old Finns used to view sauna not only for physical cleansing purposes but also for spiritual cleansing as well. Saunas used to have gnomes and spiritual guardians. Does anyone remember these?

We would like to know what the sauna represents for the Finnish Canadians and non-Finns. It is also worthwhile to know why some people have abandoned the use of the sauna or why they would not even consider taking up the practice.

Schedule

The competition will end on December 31, 1999. The prize selection committee will include Mr. Jorma Halonen from the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society, Dr. Kaarina Kailo from Oulu University, Finland, and Dr. Raija Warkentin from Lakehead University, Thunder Bay.

The results will be announced at the Finnish Grand Festival in the summer of 2000 in Toronto. The entries will then be handed over to the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society archives at Lakehead University and copies will be sent to the Finnish Literary Society, which maintains the world's largest collection of Finnish customs and oral history. A selection of the writings will be published.

Instructions

Participants are asked to write on any topic mentioned above. They may do so by typing, writing neatly by hand or speaking into a tape recorder. Both the Finnish and English languages are acceptable. Participants should use only their initials or some other alias, so that the prize selection committee will not know their true identities. Each participant should enclose a sealed envelope, including the title of their entry as well as their true name and alias, address, telephone number and a short note on when they or their Finnish parents/grandparents immigrated to Canada or which ethnic group they represent. Photographs are also welcome. Please indicate the date of the photograph and a short explanation for it. The society is willing to return photos upon request after copying them.

Prizes

Prizes will vary from books to items such as Finnish glass, jewelry and T-shirts (donated by Finnish Canadian stores and the Finnish Literary Society).

Address

Send in your entry as soon as possible to the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society, Box 3413, Thunder Bay, Ontario, P7B 5J9. Remember, the deadline is December 31, 1999.

Don't be shy!

We need your valuable input. The researchers emphasize that no memories are too insignificant to write about, and even little glimpses of the sauna culture are worth preserving for the benefit of future generations. Even a few lines are of benefit for us.

Just pick up a pen and write and send your entry in today!

Thank you for your kind interest and concern. May you and your family be blessed with peace, happiness and good health.

INTERVIEW SCHEDULE FOR FINNISH-CANADIAN WOMEN

Open-ended questions

Raija Warkentin

1. Family history of immigration.

2. Tell me about your early life in Canada. Your family members? Their occupation? What are your siblings doing now?

3. Tell me about sauna:

4. What happened in sauna? How long did family members stay in sauna?

5. Have you continued the sauna tradition?

6. What do you know about blood stopping or cupping traditions?

7. Any other healing traditions from the old country?

8. Did you get to know any Native Canadians?

9. Public health care

10. Home and community care

11. How was death viewed?

12. Were you aware of what the non-Finns thought of the healing methods or sauna of the Finns?

13. How to stay healthy?