Exploring Researchers in Dialogue: Linguistic and Educational Perspectives on Observational Data from a Sixth Grade Classroom

Helg Fottland and Synnøve Matre

Helg Fottland, PhD., Associate Professor, Faculty of Teacher Education and Deaf Studies, Sør-Trøndelag University College, Trondheim, Norway

Synnøve Matre, PhD., Associate Professor, Faculty of Teacher Education and Deaf Studies, Sør-Trøndelag University College, Trondheim, Norway

Abstract: This article reflects on a collaborative process between two researchers from different backgrounds conducting a joint-venture classroom observation project focusing on language, communication and special education. Focusing on the connection between explorative learning situations and dialogue in relation to children’s learning and identity development, the researchers cooperate on all levels in the research process. The article compares findings when approaching data from two different professional traditions, linguistics and education. The main focus is how each of the researchers approaches the data analysis. The combining of approaches in interpreting and writing is also discussed. Narratives and spoken dialogues are vital in this work; transcripts of video material from a primary school classroom are used as illustrations.

Keywords: collaboration, joint research, data analysis.

Citation information:

Fottland, H., & Matre, S. (2004). Exploring researchers in dialogue: Linguistic and educational perspectives on observational data from a sixth grade classroom. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(3). Article 4. Retrieved INSERT DATE from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/3_3/html/fottlandmatre.html

This article presents and reflects on the authors’ individual approaches and collaboration while working on a joint venture research project1 focusing on language, communication, and education. One researcher is a linguist; the other is in education. The focus in our main project is on the connection between explorative learning situations and dialogue, while our aim in this minor study is to describe and reflect on how we cooperate on all levels in the research process, from asking research questions, to collecting, analysing and reflecting on data, to reporting results.

In this article, we discuss findings from data approached from two different professional traditions. The main focus will be on how each of the researchers approaches the data analysis. The combining of approaches in interpreting and writing is also briefly reflected on. As narratives and spoken dialogues are vital in this work, transcripts of videotaped material from a Norwegian sixth grade classroom is used to illustrate central issues from the data analysis.

The recorded material used here is from a day in September when, with the municipal and county elections, just around the corner, political parties and the elections were constantly highlighted in all the media and were a natural topic for this school day. In this article, first we will give some contextual information from the selected classroom before we illustrate, each in our manner, some of the things that took place in the selected footage. Fottland attempts to capture important events from the particular session in a narrative, while Matre examines two dialogue excerpts. Thereafter, each of us separately interprets our respective illustrations on the basis of our particular academic traditions, and then we suggest possibilities for further collaborative approaches.

The scene is Sletta School, an open-plan school in a Norwegian city. The sixth-grade class we are examining shares a large area with another sixth-grade class. Their teacher, Aksel2, has arranged his section with desks clustered in groups where his pupils have their regular places in small units of four, five or six. There is a listening corner3, consisting of benches forming a horseshoe that is shielded and framed by walls and bookshelves. The walls and shelves are hung with pictures and pupils’ works. There is also a large board on the wall facing the semi-circle of benches.

This landscape is the day-to-day workplace for Aksel and his 22 pupils. The children are twelve years of age, and Aksel has been their teacher ever since they started school when they were six. A number of them have major learning difficulties and have the right to support and adapted instruction in addition to the normal teaching.

The teacher’s aim for a week-long period working on the Norwegian official election campaign is that the pupils will learn something about, and subsequently become interested in, Norway’s political parties. Secondly, he wants them to be acquainted with the election campaign leading up to the official election day. His third intention is to let the children participate in and experience an arranged school election, organised as much like the real municipal and county elections as possible.

In the narrative we present here, the children are working on a teacher-assigned task, namely to develop election pamphlets. They operate in groups, each concentrating on one Norwegian political party each. Aksel’s goal is that the pamphlets should be as informal as possible when it comes to informing others about the main features of the political party in question. Furthermore, the teacher wants the children to “use their own words” when writing the pamphlets, so that the rest of the class can easily understand them. He also encourages them to illustrate the pamphlets in a manner that will be attractive to readers, who in this context are primarily the other pupils in the class. The pamphlets should also be as much like real “adult” political pamphlets as possible. In this article we concentrate mainly on a small group of five children while they worked on their pamphlets. These five children are cooperating on making an election pamphlet for Venstre, the Norwegian Liberal party.

The teacher, all the children and their parents, gave us permission to videotape a variety of situations from this sixth grade classroom. Before we started the actual study, we also attended the class over a long period of time to become acquainted with the children and to familiarise them with us and the video cameras. We had been present in the classroom area with our logbooks and video cameras for several months when the episode we describe here occurred.

It is September and the municipal and county election campaigns are running in all the media. Grade 6b at Sletta School has launched their local election campaign. Divided into various political party groups, the pupils are designing election pamphlets. The teacher’s instructions are to prepare an informative and catchy folder about “their” party. He has also urged them to write their text in a language style, or register, that is as comprehensible as possible; “their own child language.” This is intended as an explorative task. The deadline is looming and they must finish their pamphlets during the current work session. The five “Liberals”, the girls Olga, Julie, and Mary, and the boys Svein and Kyrre, are sitting or lying on the floor and benches in a sheltered area of the classroom.

Olga has quietly but determinedly taken the lead. She asks Julie to reproduce, in her own way and in “her own words,” a text from one of the official Liberal party election pamphlets. Julie clearly finds this assignment both difficult and arduous. She objects. However, Olga remains firm and is supported by Svein, who appears to be more concerned about the group getting their pamphlet finished during this session than about what actually goes into it. His own input is minimal. Mary is only focused on what she is struggling with. She is trying to produce her assigned text in her “own words.”

Instead of starting on the job she has been given, Julie attempts a number of times to pass it on to Kyrre. Kyrre shakes his head and turns his pencil-case around without doing anything. He is signalling with his body language and facial expressions that Julie’s order to “write this here in your own words” is virtually an impossible task. However, Julie merely turns her back on his protests and instead starts instructing Mary. Julie has clear ideas on how her classmate should proceed and continues to correct her work. Mary keeps erasing and improving. Julie keeps supervising her for a while before again addressing Kyrre, this time her third attempt, who still has not started on the task she has given him.

Svein joins in, declaring that his classmate must be allowed to work on something he would like to work on, not what she has decided. Julie rebuffs this by saying that so far Kyrre has done nothing at all. The two of them discuss intensely for some minutes, across Kyrre’s head, what he should write and how he should formulate his text. Both seek support for their proposals from Olga, without receiving much response from her. Olga is busy working on her own contribution to the pamphlet. Meanwhile, Kyrre is twisting his head, looking dejectedly at the others and fiddling with a chair. Svein becomes irritated and reminds him: “Get on with it then.” “Uhuh,” responds Kyrre obediently, finally starting his writing, instructed by Svein and monitored by Julie, who insists that his letters “mustn’t crash into each other.”

The work on the election campaign in the sixth grade classroom continued past this point, but we have chosen to stop our narrative here. We have enough text to demonstrate how we, through our educator’s and linguist’s eyes, alone and together, approach this incident analytically to gain as deep and as wide an understanding as possible of what is happening during this approximately 14-minute long work session.

The selected dialogue excerpts below are from the beginning and the end of the session described in the narrative. These excerpts are chosen because they clearly show the children interacting in an exploratory way.

| 16 Olga: | (picks up a green pamphlet) OK, we copy this here then |

| 17 Julie: | What to write what am I going to write here then? |

| 18 Olga: | These pictures here ... |

| 19 Svein: | Olga, where’s this going? |

| 20 Julie: | (addressing Olga) Do I write all this here? (points down the pamphlet page) |

| (5.0) | |

| 21 Svein: | It won’t be really all that nice then |

| (3.0) | |

| 22 Julie: | Do I need to include all that there? (takes the paper and the green pamphlet over to Mary) |

| 23 Mary: | Do I write this in my own words own words? (looks at Olga) |

| (no answer from Olga) | |

| 24 Svein: | (addressing Olga) Listen up, we can’t xxx xxx if we’re going to be finished (today) |

| 25 Olga: | (looks at her watch) Sure, we can work... |

| (Kyrre comes over and sits down between Julie and Olga) | |

| 26 Julie: | What I think first of all ... |

| 27 Svein: | Julie, can’t you just put it right in here in your own words? |

| 28 Julie: | That there? (points) |

| 29 Svein: | Sure, that there (points to the sheet of paper he is holding) |

| 30 Olga: | And then somebody else can write that there |

| 31 Julie: | Yes |

| 61 Julie: | Do we have a job for Kyrre? (looks towards Olga) |

| 62 Kyrre: | Uhuh |

| 63 Julie: | (shows the sheet of paper to Svein) Were we supposed to write this in (our own words)? |

| 64 Svein: | Weren’t you supposed to do that? |

| 65 Julie: | (2.0) (appears to consider) |

| 66 Svein: | ºOkay° |

| 67 Julie: | (to K.) Will you do it? (looks at K.) |

| 68 Kyrre: | (possibly giiving a very slight nod in response) |

| 69 Julie: | Rewrite it in your own words |

| 70 Svein: | (to K.) You understand what is meant by in your own words? |

| 71 Kyrre: | That I should write what I think myself, sure |

| 72 Svein: | <no> |

| 73 Julie: | <No> you must use <another word here> (points), only it must mean the same |

| 74 Svein: | <you must use> ... |

| 75 Olga: | Shouldn’t we ask Aksel ... (says more here, but we cannot catch it. Apparently proposes that they should ask the teacher whether it is okay that Kyrre copies the text he is to work on verbatim) |

| 76 Julie: | I’ll do it (rises, picks up a sheet of paper and leaves) |

|

| (2.5) |

| 77 Svein: | (to Kyrre) Do you understand everything it says there? |

| 78 Kyree: | °I can ask somebody° |

| 79 Svein: | Hmm? |

| 80: Kyrre | Sure, at least I think so |

| (12.0) | |

| 81: Julie | Kyrre, you can write it like this |

| 82 Kyrre: | (to himself into the air) Then I can continue with this here, then |

| 83 Svein: | Yes |

| 84 Kyrre: | (nods) |

| 85 Svein: | Oh, get on with it then |

| 86 Julie: | (points at K. writing) You have to make sure these letters don’t crash into each other. |

| 87 Kyrre: | Uhuh. |

| 88 Julie: | Because then it’ll be ... |

| 89 Svein: | I think Kyrre is writing nicer now than he was before. |

Through our analysis of this short narrative and these dialogue excerpts from a work session in a sixth grade class we are seeking answers to the following research questions: What happens in the interaction between the five pupils during these 14 minutes? What motives drive the work forward? How do they collaborate, how involved are they and how do they work individually?

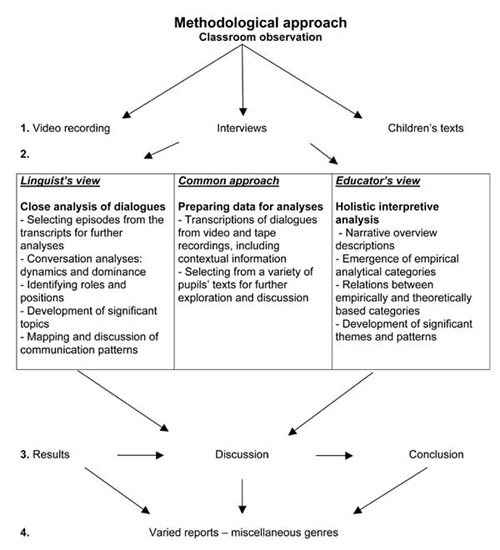

Our ambition here is not to completely answer all these questions, but to describe, explain and reflect on our different interpretative approaches, as well as to illuminate how these approaches supplement each other. Our goal is to show how we have collaborated and how that collaboration process has helped us to find answers to the research questions. We have illustrated how we are working together in a model (Model, Figure 1).

As the model illustrates, we approach common data from different positions, bearing in mind that we have collected the data in the same manner, each with our own video camera in the same teaching situation with different children and different events in focus. Our close analytical collaboration starts immediately with the initial processing of the video material (Model, Level One). Using the same rules and guidelines, we transcribe the conversations and the interaction from our parallel video recordings. We constantly discuss matters during this work process, comparing what we hear and see and supplementing each other’s transcriptions. By doing this, we obtain very full transcriptions and the discussions we have had between us represent a good start to our analytical work (exemplified by Model, Level Two, Middle Column).

Matre works on the dialogues and the pupils’ linguistic forms of expression (Model, Level Two, Left Column). Her conversation analysis is in the ethno-methodological tradition (Heritage, 1984) and the dialogism tradition as the term has been developed by Linell (1998, 2003), with interactionism, contextualism and double dialogicity as important concepts. She focuses on small units dialogue episodes and tries to discover how the informants interact with each other and how they use language and dialogues to cooperate and explore topics. She focuses on parts intending to illuminate the whole. Fottland attempts to capture a holistic picture of what happens in a narrative (Model, Level Two, Right Column). In her interpretation of the narrative she strives to find important themes by emphasizing significant details. She applies her “theoretical glasses” to identify analytical units that may contribute positively to finding answers to our research questions. Aware of the danger of over-simplification, we could explain this by saying that Fottland is working on the macro level with a holistic analysis, while Matre is working on the micro level with a close analysis.

We discuss all our analyses thoroughly with each other while working on them and at the end of our work, and in these discussions we attempt to counter and supplement each other’s reflections (Model, Level Three). Finally, we talk about different possibilities when it comes to writing our research findings in various original and appropriate manners (Model, Level Four). We believe that this research procedure, this “dialogic” way of carrying out a research process, may enhance the understanding of what goes on in a classroom.

Even though in this model we have put our approaches into static separate columns for common approach, language communication and educational use respectively this is not how our cooperation actually functions. We always have a dialogic interplay between various academic constructs and the academic fields involved. In our work, we continuously use dialogue as a tool for our learning and academic progress. Thus we actually have an interaction between the various components that have been placed in the columns in our model. In this article, we mainly focus on what happens in the columns on Level Two of the Model.

By exploiting the approaches described in the interpretation of the selected data material from the selected sixth grade classroom, and by being in continuous discussion with each other as we progress through our analyses, we have in our assessment attained a comprehensive common understanding which has made it possible for us to provide satisfactory answers to the research question of this modest study. We hope our respective analyses will help illustrate this.

The dialogues and the analyses of them constitute a substantial basis for formulating and understanding the narrative. We therefore start by analyzing the two dialogue excerpts, and then interpret and reflect upon the narrative.

In our work with the dialogues we find our basis in analytical constructs taken from conversation analysis, looking for understanding of the dialogic interaction in the group and what this may tell us about meaning making, relationships and collaboration between the children (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974; Söderbergh, 1985; Linell & Gustavsson, 1987). Initiative is an important concept in this context. When a participant initiates a new topic and thus turns the conversation in a new direction, we may call this a global initiative. A local initiative means carrying on a topic of conversation that has already been introduced. An initiative always implies expectation of a response. The response may manifest itself by a participant linking up with and developing the main content of the previous utterance (focal link). When the feedback links to a more peripheral content in previous utterances we may speak of non-focal response or linking. If an initiative does not trigger a response, we perceive this as a break, or hiatus, in the conversation. How the interlocutors receive initiatives says a great deal about the attitude to cooperation in the group.

In groups with many participants, it is always interesting to study whose utterances are being linked back to. Do participants link up to the last speaker, a previous speaker or do they show a tendency to carry on what they themselves just said? It is also interesting to look for participant structure in the conversations. Does, for example, one interlocutor function as the main speaker? Is anyone dominating the conversation? These are essential elements of dialogic interaction that may help us better understand what happens, and uncover positions, roles and power structures.

All conversations are “controlled” or motivated by one or more communicative projects. Participant contributions are always tinted by a meaning or purpose that propels the conversation forward. We may briefly call the communicative project the point of the conversation (Linell, 1998; Matre, 2000). Identifying communicative projects also sheds light on the children’s roles and positioning in the election pamphlet work. Different utterances perform different linguistic actions (Matre, 2000) in the context. They may, for example, function as explanations, instructions, answers or challenges. Labelling contributions from interlocutors provides useful information when trying to understand the interaction.

Both of the excerpts we are studying here deal with understanding and supporting a work process. The children’s apparently overarching project is to get the work going, and to determine who is going to do what and how.

Olga, Julie, and Svein participate actively in the first excerpt. Olga starts by taking a global initiative, quietly, speaking softly, but nevertheless firmly and with authority: (16) “OK, we copy this here then at the bottom.” In her initiative she serves notice what she believes the group should write, where to write and who is to do it. She is brief and to the point. Julie gets the job. Olga does not bother to ask whether she thinks it is acceptable for Julie to take on this task. “Here like this,” Olga says and hands Julie the pamphlet together with a sheet of paper. Julie does not quite understand and follows up with a number of questions in close sequence:

(17) What am I going to write here then?

(20) Do I write all this here?

(22) Do I need to include all that there?

Julie is clearly overwhelmed and sceptical of her task. She appears to be clearly hesitant and signals this by returning questions to Olga. Olga explains and gives additional instructions in response to the first question. After this it appears that Olga believes that she has finished answering. Julie’s questions are left hanging in the air. There is a hiatus in the conversation between Julie and Olga, and after the final question without any answer, Julie takes the sheet of paper and the pamphlet with her over to Mary.

Parallel to this minor intermezzo between Julie and Olga, Svein also addresses an initiative to Olga, a question regarding where an element in the pamphlet should be placed: (19) “Olga, where’s this going?” We do not register any answer from Olga. Somewhat later Mary also asks Olga a question. She would like to know how to carry out the work: (23) “Do I write this in my own words own words?” Olga does not answer this either. This sequence illustrates a central recurring characteristic in this group’s interaction: The members of the group most frequently address Olga when there is something they are uncertain of. The answers supplied by Olga are usually brief, often only “yes” or “no” or almost imperceptible nods. Quite often even expected answers are withheld, resulting in a break in the conversation. Olga appears to be the group’s unofficial authority, and in this short excerpt alone she is responsible for three breaks in the conversation. We interpret this as a strategy for the efficient exercise of power, for efficient leadership. The response from Olga is thus either brief or absent. When Olga offers initiatives, they are often concise instructions: “OK, we copy this here then” (16), “And then somebody else can write that there” (30). This recurs throughout the entire 14-minute session. In addition to instructions we see that some of her initiatives are linguistic actions such as explanations or proposals. It is interesting to note that she does not ask a single question in the first session or during the rest of the session. This is in contrast to the other participants who ask frequent questions. Olga is not the one who wonders, but the one who knows and has answers.

Olga’s use of pronouns also tells us something about her role in this group and her attitude to the group. She uses “we”:

(16) OK, we copy this here then

no, we’ll write it on the back(25) Sure, we can work

The other children use this plural pronoun only in exceptional cases. Through her use of pronouns, Olga signals her responsibility for the whole group and thus positions herself as the natural leader of the group. Her use of pronouns and her linguistic actions give clear signals that Olga is the leader. The way the other children turn to her with looks and questions confirms this role.

Close reading of the interaction tells us that Julie does not appear to be completely satisfied with this allocation of roles. She does not blindly accept instructions from Olga. We sense a looming power struggle. Julie also wants to be part of deciding how the work should be distributed. This can be seen clearly in the final utterance of the excerpt where Julie tells Olga what she can do: “Then you can write it there ...” (31). However, Julie does not appear as an authoritarian leader. She ends her instruction with “if you ...”, thus softening the impact. We may here sense that Julie has another communicative project than dividing the work between them and finishing the pamphlet. What motivates her input may be her wish to try out being a leader. We will touch on this more in the analysis of Excerpt 2.

Excerpt 2 deals with getting Kyrre to work. So far he has been sitting without doing anything. Julie fully assumes the role of leader here. Her primary project appears to be to find a job that Kyrre can cope with. At the same time we also sense another communicative project exerting controlling influence on her activity, which is to avoid too heavy a workload for herself.

The excerpt goes straight to the heart of the matter when Julie asks: (61) “Do we have a job for Kyrre?” As with Olga in the first excerpt, Julie also uses the plural pronoun “we” when exercising the role of leader. She formulates her global initiative as a question, thus inviting others to state an opinion. When there is no response she rephrases her question and after a small pause she answers herself: “You were going to try and write this in your own words.” Kyrre agrees to this, responding: “Uhuh.” But then Julie appears to become uncertain, suddenly addressing Svein (63) “Were we supposed to write this in our own words?” Svein responds, but does not link up with the main content of Julie’s question. Instead he uses non-focal linking and asks who was actually going to write the text they are talking about, (64) “Weren’t you supposed to do that?” Svein takes another stance, or footing, in the conversation than the one offered him by Julie (Goffman 1981). Julie is surprised, needs to consider and then responds by giving a reason Svein accepts: (65) “But he (=Kyrre) hasn’t done anything.” Julie then reverts to the role of instructor. She defines, explains, gives reasons and asks. She does this in an educational and friendly way. Svein supports Julie by adopting a meta-perspective on her instructions. Again his input shifts the focus. He asks Kyrre: (70) “You understand what is meant by ‘in your own words’?” In this way, Svein attempts to ensure that Kyrre understands. Kyrre then provides his explanation; Julie serves up another. Svein himself is unable to complete his explanation before Olga makes short work of it by proposing they ask the teacher, Aksel, whether Kyrre may copy the text in question verbatim. Olga is solution-oriented in her input. It is important that Kyrre also finishes his contribution to the pamphlet. This input from Olga propels the group further in their work. Julie goes to ask Aksel and passes the answer back to Kyrre in exemplary fashion. Kyrre reports that he understands and he starts to work.

One might assume that Julie and Svein would now start doing their own work, but they do not. They continue monitoring closely what Kyrre does, continuing firmly in their leadership roles. Their statements link to what Kyrre is doing. Svein asks Kyrre to get on with it, while Julie is concerned with the layout, and the way Kyrre is writing his letters. She asks him to not write his letters so packed together, and explains why this is important: (88) “If we’re going to copy, then it’ll be, it may be that it’ll be crumpled together like.” The excerpt closes when Svein evaluates Kyrre’s effort: (89) “I think Kyrre is writing nicer now than he was before.” This utterance illustrates something we see a number of times during the 14 minutes we are examining here, a feature that says something about positions within the group. Julie and Svein and even Olga quite often speak about Kyrre in the third person. They speak over his head about him: (65) “But he hasn’t done anything.” In such utterances they reduce Kyrre to a case. We see the outline of a hierarchy in the group where Olga is the uncontested leader with an eye over the whole group and the totality of the work. Julie and Svein function as middle management, as it were, supervising those with the lower positions, such as Mary and Kyrre, and ensuring that they are doing what they are supposed to. Olga instructs confidently and without hesitation using directives. Julie tries out her role as leader in a more uncertain and inviting manner by asking questions.

The excerpts show pieces of a dialogic interaction. Both excerpts deal with supporting work processes. The participants link with what is being done by way of work in the group and comment on it. We thus witness little development of topics between the children. They do not discuss what the Liberal party stands for, what issues they think are important, or what content the brochure should impart. The conversations appear to be relatively fragmented, with many hiatuses, non-focal links, and frequent pauses. We conclude that the children make little use of conversation as a tool to explore various questions or topics. We see a minor attempt at exploration of a topic by means of language in the short sequence following Svein’s question: (70) “You understand what is meant by ‘in your own words’?”

The conversation is rather about what they are supposed to be doing. The children use the conversation as a way of supporting the practical work of making the election pamphlet. They are most focused on how to “patch” together a pamphlet with slightly rewritten clippings from various sources, and on splitting up the work in a more or less fair way. The conversation shows that their work is strongly controlled by the instructions they have received from the teacher on how to prepare this pamphlet and write the text for it in “their own words” (Säljö, Riesbeck, & Wyndhamn, 2001). The children are busy doing what they have been asked to do. We hear the echo of the teacher’s voice in many of their statements (Bakhtin, 1981). They keep coming back to how they must write “in their own words.” The task and the instructions the pupils have been given appear to invite this type of disconnected conversation with few examples of coherent development of the topics. The teacher’s influence appears to be strong in this classroom talk, even though he is not participating or intervening directly in the conversation (compare to Fisher, 1997).

The conversation also appears to a large extent to be controlled by the wish of some of the pupils to position themselves within the group. Julie is the clearest exponent for this. Her main communicative project appears to be to lead and direct the work. Several of the children seem to be more engaged in positioning themselves and distributing the work among themselves than in exploring the political themes that are supposed to be in focus. The degree to which the conversation between the children has an exploratory nature, it is seldom in relation to the themes, but mostly in relation to roles. The conversation analysis shows how Svein and Julie use their utterances to try out the middle-manager role. The analysis also reveals a clear hierarchical organization of the group. With such communicative projects in focus, there appears to be little room for exploring the themes. There is little evidence of exploratory conversation in an interaction that is controlled by such communicative projects.

The verbatim transcripts, together with notes from observations and tape-recorded transliterated teacher interviews have been briefly analysed, then written as a narrative, trying to capture the essence of what happened in the real classroom situation. In this putting-pen-to-paper process we use research that perceives narratives as effective aids when connecting meaning to experiences (Bruner, 1997; Gudmundsdottir, 1996; Mishler, 1986). We also look upon the narrative structure as a “realist” tale of happenings from real life (Van Maanen, 1988).

From the narrative we select significant themes which we find to be especially important for understanding what comes to pass while these school children collaborate. Interesting themes which characterize the pupils’ work processes, both as a group and as individuals, emerge on this interpretation level. We reflect on these emergent themes theoretically through “theory lenses”, using an inductive, hermeneutic approach (Ricoeur, 1999). In our hermeneutic analyses of this particular situation we find it appropriate, as will be seen, to make use of various motivational theories as the main interpretation framework.

Throughout this elucidation process, enlightening theory-based empirical topics that were specifically interesting in terms of understanding the children’s motivational processes in the situation became apparent. We describe and analyse these selected subject matters, trying to find answers to how the children make the election pamphlet, and why the pupils carry out the assignment in the ways they do.

The starting point for the Liberal group and their endeavours is the instructions from the teacher. Aksel wants his pupils to acquire more knowledge about their political party and that they should present their own insight to their classmates in an election pamphlet that is easy to read. He asks, moreover, that the pupils prepare their pamphlet within a stipulated deadline. The common aim of the pupils therefore, reasonably enough, is to follow his instructions. They are externally controlled (Deci & Ryan, 1994). If they are to attain their goal, they will have to cooperate well as a group and each of them must do a good and efficient individual job. Therefore in the initial phase of the work session they are occupied with deciding what they should do to resolve the task in the best way possible, as presented in the narrative, the two dialogue excerpts and the close analysis, by attempting to establish who should do what and how to coordinate and carry out the task. Because the “Liberals” do not initially find satisfactory solutions to these questions, they do not develop any common understanding of how they can and should carry out their task. They are unable to act together and therefore experience problems as a group from the very start. The children do not reach any inter-subjective understanding of what should happen during the work session (Wertsch, 1984). Instead of agreeing on what to do and how to share the work together, on the way to a common goal, each individual is left to fend for him or herself and handle his or her own progress.

So how strong is each individual child’s motivation, one wonders? What is it that drives Olga, Kyrre, Mary, Julie, and Svein when working on the pamphlet? Are they genuinely concerned with learning about and understanding the Liberal party’s election platform in a way that would enable them to present knowledge to their classmates? This was what Aksel wanted them to achieve when he assigned the class this task. Or are the children perhaps primarily concerned with developing a product the teacher will be happy with, and which the rest of the class will find pleasing? Below we shall focus on each of the children, reflecting on these issues by using constructs from the theories of self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1994), expectation value (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992) and goal orientation (Nicholls, 1983, 1989; Urdan, 1997).

Olga knows what she wants. She would like the group as a whole to deliver a successful product, and she wants to do a good job herself. Quietly she is pulling strings to make the others carry out tasks she feels are correct and important for their joint success. However, she does not seek anybody’s advice, neither concerning tasks she assigns nor the job she delves into herself. It appears that for her own part, Olga has internalized Aksel’s external regulation of the group. She attempts to get the others started, and she is actively occupied herself. Nevertheless, she does not at all consider what her classmates might possibly be interested in and motivated to contribute. Even if she has been instructed to perform the task she is carrying out personally, she completes it in her own special way, and it appears that she is completely involved in the work. It appears that she has identified with the teacher’s requirement regarding desirable pupil behaviour. Olga has apparently undertaken an identified regulation (Deci & Ryan, 1994) by approving the teacher’s plans for the “Liberals” as important and valuable for herself personally.

None of the other children does anything close to this. Julie and Svein translate the teacher’s instructions to mean that they should make sure that Kyrre, and also Mary, are working as they should and that they finish in time. But these two “middle managers” do nothing much themselves. Mary complacently adjusts her behaviour in keeping with Julie’s instructions. There is every reason to believe that she is doing her best to satisfy external requirements, including those coming directly from the teacher and those interpreted and presented by her classmates. Kyrre in contrast is not easy to motivate. It appears that he has more or less relinquished any idea of accomplishing anything at all.

According to expectation-value theory (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992), the motivation of pupils is influenced by how much they appreciate the tasks they are assigned. Because Aksel is highly respected by the pupils in Class 6b, it is probably important for all five in the Liberal group that their teacher is pleased with the work they are carrying out, and that he finds that their joint final product is good. Furthermore, it is also probable that some of the children envision that a job well done will mean that the teacher will see them as clever pupils, and that such a positive assessment could be useful in the long term.

There is reason to assume that three of the pupils, Mary, Julie, and Svein, are particularly influenced by such utilitarian considerations when they are working, and that these ideas highly influence their motivation and behaviour. It appears, moreover, that coping with the task has taken on personal value for the two girls, probably because success would also strengthen their own confidence in themselves and their own skills. If they fail this, their confidence will be undermined. It is difficult to say much about Svein’s value motives. It appears that for him the most incumbent matter in this situation is to finish the task within the deadline. This does not appear to have any consequences for him when it comes to what he does himself, but he compensates by actively hustling the other members of the group along.

Svein behaves carefully in relation to Olga. None of the other children takes any initiative when it comes to approaching her, other than to ask what she thinks they should do. Olga, for her part, appears to work with stolid satisfaction. For all intents and purposes, she appears to have developed an internal genuine interest in the topics in question and in the design of the pamphlet. The work has taken on an intrinsic interest for her, which leads her to work with motivation and satisfaction through the entire work session. She apparently is confident that she will succeed in her undertaking, in contrast to the other four Liberal candidates. She expects to master her task, which the others do not appear to do.

Kyrre would probably like to please both the teacher and himself. However, he is simply unable to accomplish anything. In spite of repeated attempts by Julie and Svein to get him started, he is floundering. None of the tasks appears to be sufficiently interesting and enjoyable. He probably finds, moreover, that the assigned tasks are too demanding, and that he would have to expend too much toil and trouble to realize them. He may even think that it is absolutely impossible for him to cope with any of the tasks the others propose that he should do.

Julie probably reasons in a similar vein, as she reacts so negatively to Olga’s instructions as to what she should contribute. Svein apparently also seems to find that too much is required of him to do something relevant during this session. As is the case with Julie, he also attempts to induce others to do the work that he could just as well have done himself, if he had only had the energy to get started.

Which are the learning targets of these young Liberal politicians? Our aim is to ascertain whether any of them are explorative and task-oriented, as the teacher would like them to be. We also aim to uncover any ego-oriented and socially-oriented behaviour they might have (Nicholls, 1983, 1989; Urdan, 1997).

During this brief sequence of events we see only the beginnings of exploratory behaviour. It might be that Olga is quietly undertaking an exploratory activity in her approach. At the very least she is actively attempting to gain greater insight into Liberal politics, and she is trying to present her knowledge in a comprehensible manner in the pamphlet. From the narrative it clearly emerges that Olga is task-oriented. She takes the teacher’s instructions seriously. She quietly, but doggedly, attempts to get the other four to carry out targeted work. Moreover, on a personal level she actively attempts to do a good job, apparently only for the sake of the job itself and not to attain any personal advantages. Olga is simply seeking insight and understanding in a field she has personally become involved in.

It may also be assumed that Mary is significantly task-oriented. At any rate, she is attempting to carry out the task the teacher and her classmates plan for her to complete. She is not fully able to carry out external requirements in an independent manner. She is nevertheless working hard and apparently does not care very much what the other group members think about her as a person. All the same, she listens to their views when it comes to how her task can and should be resolved.

The three remaining pupils, Julie, Svein, and Kyrre, are all ego-oriented, albeit in very different ways. Julie is concerned with succeeding as a leader. It might be that she is trying to avoid doing the task Olga gives her, as this places too high demands on her, therefore feeding a fear of failure. To have her talents recognized by her partners, she instead attempts to demonstrate her skills by controlling the activities of the two pupils in the group she feels superior to, namely Mary and Kyrre.

Svein appears to be most concerned with social goals. He wants the group work to progress easily, but he himself contributes minimally to the group. He appears to have a good enough time in the group, but he does not seem to have any particular ambitions on his own behalf. The last of the pupils, Kyrre, does not appear to have any target orientation at all. He has probably failed with such a frequency during his six years of school that he has developed a fundamental sense of learned helplessness (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978).

As far as we can ascertain, only Olga displays genuine interest in learning anything about the Liberal party during this session. She also wants the group to succeed in designing an attractive reader-friendly pamphlet. Olga identifies with the task, and it has value for her. She has become interested. Even though she does not personally manage to cooperate very well with the rest of the group, she is working in a concentrated way on the form and content tasks, and she has a clear expectation of succeeding. The teacher’s instructions obviously match her personal wishes and desires. He probably meets her precisely in her proximal zone of motivational development (Brophy, 1999). Thus, the learning activity planned by Aksel matches Olga’s individual characteristics in a way that stimulates her interest in further learning (Bråten, 2002a, 2000b).

The motivation of the rest of the group appears to be exclusively connected to form. All four have the aim of producing a nice pamphlet. It does not, however, appear to be so important for them what is actually in this pamphlet, only that it looks good and proper. Presumably they do not understand so much of what they are describing. In terms of content, it appears that the task in itself has no particular value for any of them. They relate to external demands regarding form and time schedules and in general appear to be ego-oriented.

When we read and interpret this brief narrative in a socio-cultural frame of understanding (Vygotsky, 1978), we see clearly that something more than individual personal factors influence the motivation of the group members. Social and cultural elements also have great importance for what happens. Our observations concur with Wadel’s (2002) perception that motivation is a relational concept, and a phenomenon that is greatly mobilized between persons in contexts.

Because the teacher’s task appears to fit Olga’s motivational development zone so well, she is able to transfer the external impulse from him to genuine intrinsic interest, to an inner motivation. This motivation propels her when working with both academic content and form. The other four pupils are regulated externally during this entire session. Their behaviour is controlled by how each of them interprets the teacher’s instructions, or through classmates managing them through adopted teacher voices.

Based on these reflections we allow ourselves to claim that the motivational surroundings of the Liberal group functioned positively when it came to supporting the inner drive of one of them, Olga. The narrative documents how optimal matching of tasks and personal characteristics, content and teacher support may contribute to a positive learning development (Brophy, 1999). The other pupils, on the other hand, did not have the same experience. The teacher’s instructions and the task did not echo in their proximal zone of motivational development. Moreover, peer guidance and communication did not provide sufficient stimuli to motivate them to a whole-hearted effort with the election pamphlet. Thus they did not experience the work situation as meaningful, and for that reason they probably did not learn much.

We have verified the description and interpretation by taking a preliminary draft of the narrative and the analyses to Aksel, the teacher (as per Merriam, 1988; Miles & Huberman, 1994), and later incorporated his comments into the final study. We collected this feedback in informal conversations with him where we asked: Is our description of the incident and the reaction accurate? Are the themes and constructs we have identified consistent with your experiences? Are there any themes and constructs we have missed? If so, have you additional suggestions?

The two analyses show us the interlocutors and the relations between them. We learn about the children’s positions in relation to each other and the group (their positions), we learn about each pupil’s intentions and motivation (their projects) and the way in which they work and interact (their procedures). Normally, we would thoroughly discuss and reflect on our findings. As the main point of this article is to discuss aspects of the methodology of our collaborative process, as we pointed out at the beginning of this article, we will not go more deeply into our findings here.

The most important experience we have gained from our research collaboration process so far is that we see and understand much better together than we would have done on our own. Being two interlocutors, equally familiar with the empirical findings throughout the research process, offers many advantages. One of us will propose an idea and bounce it off the other, and the other way round. Theory constructs from two academic fields are brought together and challenge each other. Thus we supplement each other and bring additional elements and ideas into the analyses, broadening their horizons and giving them richer nuances (Geertz, 1973). A greater number of components are included in the hermeneutical circle, making the answers to our research questions fuller and more enlightening.

An example of how our analyses supplement and support each other is the case where Julie with a brief, careful but significant utterance challenges Olga’s leadership position (see statement 31 from transcript). The narrative and the educator’s holistic analysis did not initially capture this utterance which provided important information about Julie and her role and projects in the interaction. We have not adjusted the narrative in relation to this information because here we want to illustrate how one analysis supplements the other.

Another example is the positive way Julie gets Kyrre started on his work. The educator’s analysis focuses on the fact that Julie attempts to shift her work tasks to others. The conversation analysis shows that she also delegates the task in a manner that is educationally sound and inviting. The use of both views contributes to a more correct picture of Julie and the interaction between the children, and helps us to discover more nuances in the material. Two viewpoints therefore ensure the quality of the analyses.

These were two small examples of how we supplement each other’s analyses, how we reflect on separate representations and interpretations. So far the benefits of our collaboration process have been that we have complemented each other’s analyses. The conversation analyses correct and supplement the narratives. The narratives help to construct thicker contexts which then help to expand the foundation of reflections in the conversation analyses. At the moment we are working on developing an integration of our two analytical approaches where we present the conversations in transcribed form as part of the narratives, and where the analyses and reflections then also comprise an integrated whole. In such close collaboration we can see that we will have to be more prepared for disagreement and contradictions. Our experience is that controversy between us, both in relation to theory and empirical data produces greater insight.

The disadvantage of a collaborative process such as ours is primarily that it is time-consuming. We occasionally find, moreover, that our writing overlaps and we repeat each other. There are also times when we might not agree so readily on the use of academic terminology. We use constructs that may have much in common but nevertheless do not cover each other completely. A case in point is that a “communicative project” in the conversation analyses is not the same as motivation in the educator’s interpretation. These constructs are nevertheless closely related. Thus we must always take great care to define the meaning of the constructs we use to each other.

Having said that, the advantages by far outweigh the disadvantages. The dynamic interaction between us is inspiring. We learn from each other all the time and that is a major benefit and great fun. There is no doubt that together we perform better.

1. The foundation of this paper is a large cooperative project based on language/communication science and education/special education. The title of the project is Den utforskende eleven og samtalen. Dialogen som verktøy for læring og personlig vekst[The exploring pupil and dialogue. Dialogue as a tool for learning and personal growth]. We focus on explorative learning situations and study the role dialogues play in learning and personal growth for pupils in the primary and intermediate stages. Our overarching aim is to gain better insight into motivation, learning and development potentials connected to the use of dialogue in explorative activities. In the project, we have cooperated on all data collection and thus we have the same empirical findings that we have reflected upon while in the collection phase. Due to our different academic backgrounds, we have dealt differently with the information that we have collected. However, we have been in continuous dialogue with each other also during the data-analyses and putting-pen-to-paper periods. We write papers, articles and book chapters both together and separately. In this paper the two of us have jointly composed and written the introduction and the conclusion/discussion sections, whilst we have been working individually on writing about our various analytical approaches.

2. All the names in the article are pseudonyms.

3. The term “listening corner” (or “class-circle”) is used in Norway to describe situations where pupils sit in a semi-circle facing the teacher and the blackboard. Most often the teacher assembles the children in such circles when starting and finishing school days. The class-circle is also frequently used when new material is being taught or when the teacher wants to talk to the pupils or get something done with all the pupils gathered in one place. Back to text

4. Transcription legend:

(Italics) Information about context and facial expressions, gestures and other non-verbal actions

xxx xxx Words or sequences that are hard to understand

(I’m writing) Words or sequences we are uncertain as to whether we have heard correctly

° ° The speaker speaks softly

< > Angle brackets in subsequent utterances mean overlapping or simultaneous speech

not Underlining means emphatic stress

... The speaker interrupts himself/herself

/… The speaker is interrupted by others

(.) Pause of half a second or less

(2.0) Pause, length written in seconds Back to text

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. P. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49-79.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin (M. Holquist, Ed.). Austin: University of Texas.

Brophy, J. (1999). Toward a model of the value aspect of motivation in education: Developing appreciation for particular learning domains and activities. Educational Psychologist, 34, 75-85.

Bruner, J. (1997). Utdanningskultur og læring [Education culture and learning]. Oslo: ad Notam Gyldendal.

Bråten, I. (2002a). Indre motivasjon i individuelt og sosialt perspektiv [Inner motivation in an individual and social perspective]. Pedagogisk Profil, 9, 4-5.

Bråten, I. (2002b). Selvregulert læring i sosialt-kognitivt perspektiv [Self-regulated learning in a social-cognitive perspective]. In I. Bråten (Ed.), Læring i sosialt, kognitivt og sosialt-kognitivt perspektiv (pp. 164-193). Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1994). Promoting self-determined education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1, 3-14.

Fisher, E. (1997). Educationally important types of children’s talk. In R. Wegerif & P. Scrimshaw (Eds.), Computers and talk in the primary classroom (pp. 22-37). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Oxford: Basil Blackwell

Gudmundsdottir, G. (1996). The teller, the tale, and the one being told: The narrative nature of the research interview. Curriculum Inquiry, 26, 293-306.

Heritage, J. (1998). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Linell, P. (1998). Approaching dialogue: Talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Linell, P. (2003). Dialogical tension: On Rommetveitian themes of minds, meanings, monologues, and languages. Mind, Culture, and Activity: An International Journal, 10(3), 219-229.

Linell, P., & Gustavsson, L. (1987). Initiativ och respons. Om dialogens dynamik, dominans och koherens [Initiative and response. About the dynamics, dominance and coherence of dialogue]. SIC 15, Tema Kommunikation, University of Linköping.

Matre, S. (2000). Samtalar mellom barn: Om utforsking, formidling og leik i dialogar [Conversations between children: About exploration, presentation and play in dialogues]. Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. H., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. An expanded sourcebook. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mishler, E. G. (1986). Research interviewing Context and narrative. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nicholls, J. G. (1983). Conceptions of ability and achievement motivation: A theory and its implications for education. In S. G. Paris, G. A. Olson, & H.W. Stevenson (Eds.), Learning and motivation in the classroom (pp. 211-237). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1999). Eksistens og hermeneutikk [Existence and hermeneutics]. Oslo: Aschehoug in cooperation with “Fondet for Thorleif Dahls kulturbibliotek” and “Det norske akademi for sprog og litteratur.”

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking in conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Söderbergh, R. (1985). A model for description and evaluation of the communicative performance of adult-child dyads in a free play situation. Lund, Sweden: Lund University

Säljö, R., Riesbeck, E., & Wyndhamn, J. (2001). Samtal, samarbete och samsyn: En studie av koordination av perspektiv i klassrumskommunikation [Conversation, cooperation and consensus. A study of coordination of perspectives in classroom communication]. In O. Dysthe (Ed.), Dialog, samspel og læring (pp. 219-240). Oslo: Abstrakt forlag AS.

Urdan, T. C. (1997). Achievement goal theory: Past results, future directions. In M. L. Maehr & P. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in Motivation and Achievement (pp. 99- 141). Greenwich, CT: JAI-Press.

Van Maanen, J. (1988). Tales of the field. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wadel, C. (2002). Den mellommenneskelig forankring av læring. Praksisfellesskap og læringsforhold [The inter-personal basis for learning. Practice community and learning]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 5, 416-422.

Wertsch, J. V. (1984). The zone of proximal development: Some conceptual issues. In J. V. Wertsch & B. Rogoff (Eds.), Children’s learning in the “Zone of Proximal Development.” New Director for Child Development, 23, (pp. 7-18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12, 265-310.