| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (2) June 2005 |

Pursuing Both Breadth and Depth in Qualitative Research: Illustrated by a Study

of the Experience of Intimate Caring for a Loved One with Alzheimer’s Disease

Les Todres and Kathleen Galvin

Les Todres, PhD, MSocSc (Clin Psych), BSocSc, CPsychol, Professor of Qualitative Research and Psychotherapy/Reader in Interprofessional Development, Institute of Health and Community Studies, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, Dorset, United Kingdom

Kathleen Galvin, PhD, BSc, RGN, Professor and Head of Research/Chair in Health Research, Institute of Health and Community Studies, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, Dorset, United Kingdom

Abstract: In this article, the authors explore the methodological and epistemological tensions between breadth and depth with reference to a study into the experience of caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease. They consider the benefits and limitations of each of two phases of the study: a generic qualitative study of narrative breadth and a descriptive phenomenological study of lifeworld depth into selected phenomena. The article concludes with a reflection on the kinds of distinctive knowledge generated by each of these two phases and the benefits of their complementary relationship with one another.

Keywords: generic qualitative interviewing, descriptive phenomenology, Alzheimer’s, caring, lifeworld depth, narrative breadth

Citation

Todres, L., & Galvin, K. (2005). Pursuing both breadth and depth in qualitative research: Illustrated by a study of the experience of intimate caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(2), Article 2. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/4_2/html/todres.htm

Authors’ Note

We would like to thank Immy Holloway, Jo Alexander, and Anita Somner for their helpful commentary on previous drafts. We would also like to thank Mervyn Richardson, our informant, coresearcher, and coauthor in the nonmethodological articles.

M had been caring in many ways for his long-time wife and partner, L, who had developed Alzheimer’s disease. What is the nature of such caring? This is a complex and pervasive question. M wanted to contribute his experiences as a source for analysis and reflection so that others could benefit. He approached us because he had become aware of the kind of research we did and believed that we could carry forward significant meanings of his experience in a rigorous manner and into a more public arena.

In two other articles (Galvin, Todres, & Richardson, 2005; Todres, Galvin, & Richardson, unpublished), we have pursued the substantive findings that were generated from the study. The present article, however, has a methodological focus, in that we wish to tell a story of breadth and depth in qualitative research.

We approached the study in two phases. In Phase 1, we pursued and analyzed a generic “grand tour” interview to generate a broad thematic understanding of the caring narrative. Phase1 might be best conceptualized as a generic qualitative study of narrative breadth. This yielded a certain level and kind of knowledge, which we wish to characterize and reflect on within the course of this article.

In addition to the value of this phase of the study in its own right, this breadth phase inspired a more in-depth study of particular selected phenomena indicated within the broad narrative. Thus, in Phase 2, we pursued a descriptive phenomenological study to elicit descriptions of a number of concrete experiences in depth. This yielded further knowledge that we wish to characterize and reflect on with reference to its value and purpose. The essential methodological thrust of the article is to consider:

We conclude by considering how such attention to narrative breadth and lifeworld depth is able to portray a rounded view of human existence that respects both the substantial embodied gravity of living through given experiences and a degree of freedom by the person to interpret these given experiences in creative ways.

Breadth and depth are not necessarily about numbers of respondents or sample size but about focus. Single-case studies can yield findings that are attuned to focusing on very specific and highly textured details within their unique context. Depth, in this sense, refers to the density of contextual information. For instance, Meier and Pugh (1986) suggested that contributions to knowledge and new insights to care can be generated by focusing on individuals in their unique context.

However, single-case studies might also yield a certain kind of breadth that can show how a unique individual life meaningfully organizes broad and fundamental human themes. The value of cases in representing life events and exploring insights from individuals’ perspectives as single, bounded entities has been discussed in the context of a range of case study and life story work (Abramson, 1992; Merriam, 1988; Miller, 2000; Platt, 1988). Such case studies show how human beings face a vast integrating task of breadth that straddles personal time and interpersonal space and is best characterized by the terms personal identity and narrative journey. Both of these types of breadth and depth are particularly suited to a single-case study approach, and it is within the spirit of these concerns that the present study could be considered valuable. The transferability of insights thus forgoes immediate empirical generalization but gains the human authenticity of someone living their life. If such insights can be transferred, they are grounded generalizations that can retain the intricate texture of “what they are about.” The danger of empirical generalization is that it can too easily rely on counting, forgetting the complexity of what it is counting.

As researchers, we needed to start in a way that was very open ended, because we knew little about what the important experiences and issues were from M’s point of view. We wanted the study to be person centered initially and informed in a relatively open-ended manner by M’s concerns, priorities, and sense of narrative organization. Such a complex phenomenon is not easily defined and is contextualized within an interrelated life of multiple meanings. Therefore, in Phase 1, we asked the question, Please can you tell us in your own words about your story of caring for L from the very beginning of her illness.

This interview of narrative breadth gave us an evocative sense or intuition of significant phenomena that had been lived through in great detail and texture. Our dilemma was whether to interrupt the sense-making narrative and “go down” into these phenomena. We chose not to do this; instead, we pursued these more focused concerns in Phase 2 of the study. It was at this stage that we could ask for a phenomenological description of a specific experience in greater depth; for example, Can you relate an experience where you realized that L’s memory was not serving her anymore and where you had to respond to this? In the tradition of descriptive phenomenology (Giorgi, 1985; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2004), we followed this up with encouragement to describe such times in specific and concrete ways (see Kvale, 1996, for guidelines on phenomenological interviews that elicit lifeworld descriptions), so the complexity of the phenomenon asked us to honor both its sense-making breadth and its lifeworld depth.

Having been engaged in both kinds of interviewing in the past, that is, generic qualitative and descriptive phenomenological interviewing, we had noticed some differences in the kinds of narratives and meaning that emerged. We wanted to explore these differences, benefits, and limitations in an empirical way, along with the kind of emphasis and knowledge that each produces.

Through participation in an open-ended, generic qualitative interview, M was given maximum freedom to tell his story of caring in his own way, allowing him to express the sequence and priority of events and meanings as they emerged for him. Here, we were interested in his narrative journey as a whole, the central issues that it raised for him, and how he made sense of this journey.

We undertook two stages of analysis: a thematic analysis, which produced three core clusters of meaning, and a narrative characterization of his changing personal identity and role.

Broad clusters of meaning

In this article, we are unable to provide the full text of our results of this phase (see Galvin et al., 2005) but wish to indicate sufficient detail so that the kind of knowledge produced can be characterized and reflected on. The three clusters of meaning are therefore briefly indicated as follows.

This summary of themes can give a broad sense of the multiple levels of tasks and challenges that M was negotiating at different stages of his journey. Understanding the breadth of such detailed meanings allowed us to arrive at a narratively coherent characterization of M’s emerging caring role, which we articulated as the unique position and task of the intimate mediator.

Narrative identity: The intimate mediator

This section of our findings is produced in some detail to indicate sense-making breadth as the kind of knowledge centrally achieved by Phase 1 of our study (Galvin et al., 2005):

The narrative and thematic analysis shows how M participates as a complex mediator between public and private worlds. On one hand, he is an intimate participant in the ongoing everyday journey with L, being changed by, and being faced with, the challenges of what this means for her life and their lives together. Such intimate participation constitutes both a kind of passion as well as a kind of knowledge which no-one else can represent. On the other hand, M is increasingly the representative and advocate for L to the outside world, as well as the translator of events of the outside world for L. He faces both ways at different times and often simultaneously, and both directions carry challenging tasks. As such, he is the “carrier” of complexity.

Becoming increasingly public with his advocacy requires paradoxically that he engages in and draws on an increasingly intimate knowledge of how L is, as her ability to communicate recedes. Increasingly, her living and responses are her communication and this needs to be understood and translated by the “intimate mediator.” So there are two crucial and unique components to the role of the intimate mediator that few people can provide, and they reflect both the “head” and “heart” of meaningful care. The “head” dimension refers to the level, depth, uniqueness and complexity of the kind of local knowledge that can only come out of the ongoing processing of everyday living together. As such, the intimate mediator is the embodiment of local knowledge. This provides the uniqueness that can only come from a narrative coherence that “tracks” the “before” and “after.”

The “heart” dimension refers to the passion and dogged determination that come from such historical intimacy, what they are trying to hold on to and the changes they are going through together; its poignancy, tragic dimensions and small joys. It is only this passion that adequately speaks of “this person who matters” and therefore provides the most meaningful “driver” for striving to meet L’s needs; it sustains a depth of meaning in the term “continuity of care” that few other dimensions can give. (p. 8)

Therefore, M’s narrative identity was the phenomenon most centrally articulated by this Phase 1 study of sense-making breadth: a complex mediator between private and public worlds, one who is both intimate participant and interpreter, who embodies both a kind of passion and a kind of local knowledge, who is the “carrier of complexity” and the driver of continuity of care. It is a level of meaning that encompasses the narrative trajectory broadly as a whole, as well as broadly covering a range of issues and tasks in an indicative way.

We would now like to consider the values and limitations of this phase.

The value of the breadth phase

Open-ended inquiry. This type of inquiry addresses the complexity of a phenomenon in an open-ended way. Such an approach uses a “broad brush,” whereby the boundaries and foci of an experiential phenomenon are not initially clear. This focus allows maximum freedom for emergence; without this, phenomena would be named and formulated prematurely. Rather, in this open-ended approach, the later delineation of phenomena emerges in a dialogical way for further exploration in the deeper second phase. This is particularly relevant in the caring sciences, where the phenomenon is normally complex and historically dense. For example, in our study, the phenomenon of caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease is a complex historical journey that is made up of a number of defining and pivotal experiences. The breadth question (What is it like to care for a loved one in such circumstances?) allows the respondent maximum freedom in expressing the range, scope, and boundaries of the complex experience.

Narrative coherence. This broad-brush focus highlights the historical and narrative sequence as a whole. During explication of such a sequence, the narrative identity of the person living through this can become clarified and articulated. In our study, this narrative identity of being the one that lived through this history was characterized as the intimate mediator. The value of such characterization of narrative identity is the ability to make sense of the whole experience, giving coherence and a sense of “person-ness” in response to the question of what it is like; it thus formulates the essence of the journey as a whole.

Therapeutic value. In addition, the meaning of the narrative that emerges might serve a therapeutic function for the carer in making sense of the complex journey. We imagine that other carers could read this “identity story” and find resonance and coherence in the characterization of the intimate mediator. The articulation of narrative identity could also help other carers and professionals make sense of these disparate experiences and give direction to how the uniqueness of such an identity can play a role in decision making and treatment plans.

Political value. The narrative identity of the intimate mediator can serve a political value, in that it emphasizes how the carer holds local knowledge that no one else possesses. Such knowledge can empower recommendations for care planning and policy making; to advocate a unique role that had not previously been addressed by policies or guidelines.

Limitation of the breadth phase: Premature closure

The nature of the interview was nondirective and, as such, did not actively focus on concrete elaborations of certain important experiences at this stage. In not wanting to interrupt the open-ended flow of narrative sequence, this interview style is thus unable to elicit more in-depth lifeworld descriptions. Experiences were named and sometimes elaborated on but were not often described in enough concrete detail to elucidate the structure of the lifeworld phenomena, such as “learning to live with L’s memory loss” or “the transition to living apart.” Once named, these phenomena require concentrated study in their own right, so that in the breadth phase, some phenomena are not explored, even though they are compelling. We became aware of how this breadth phase was prematurely summative at places that were asking to be opened up. Therefore, the value of the breadth phase is also its limitation, in that it achieves a broad-brush coherence. The downside of this coherence is that it makes it look too tidy. Such coherence asks for openings. When we did Phase 2 of the study, concentrating on named phenomena in greater depth, we realized much more about the specificity and complexity of what had initially appeared broadly coherent.

Therefore, in Phase 1, an evocative credible description of narrative identity (the intimate mediator) was achieved. However, it did not give us a detailed or nuanced understanding of how a number of lifeworld experiences were lived or were constituted as meaningful structures in their own right. Here we come to the need for a descriptive phenomenological phase.

In this next phase, we wanted to go down into six named experiences and look at each one as a lived experience in its own right, thus pursuing lifeworld depth. The final task was to consider both Phases 1 and 2 in relation to one another to understand their relative merits, limitations, and complementarity.

Six phenomena were suggested by our Phase 1 interview. We chose these six phenomena because they were compelling and evocative for M, for us as researchers, or, most often, for us all. We could have focused on more or fewer named phenomena, but these were the ones that stood out. The essential descriptions of these experiences cannot be presented in any depth in this article because of space limitations. We have thus chosen to present one of these descriptions in some detail to indicate a flavor of the nature of the depth achieved but will first list each of the phenomena studied, together with an indicative sentence or two. They were

We felt that each of these phenomena was based on events and experiences that needed to be described more fully, so we followed descriptive phenomenological guidelines to elicit the textures and structures of each (Todres, 2000, 2005; Todres & Holloway, 2004). Informed by the notion of the lifeworld, this approach moves from the particular to the general and uses thick descriptions of concrete and everyday experiences that people live through as a crucial starting point for further analysis and reflection. It also entails the gathering of detailed exemplars and illustrations.

The interview is more focused than an open-ended generic interview, in that a researcher seeks a concrete description of a “happening” that illustrates the phenomenon. It follows the logic of Can you describe a situation where…? Researchers then analyze the text of each phenomenon according to the steps of the discipline, which allow them to go back and forth between detailed meanings and the sense of the text as a whole. In this regard, Giorgi and Giorgi’s (2004) recommendations were helpful and resulted in an essential structure that characterized each of the six selected phenomena in such a way as to articulate their rich and detailed structures.

Again, to serve the methodological concerns of this article, we will present only one of the six experiential phenomena: learning to live with L’s memory loss. This gives an indication of the intricacy of meaning that emerges when we go down from breadth of meaning and flesh out a crucial component of the breadth phase structure that was previously referred to as Something is wrong.

Learning to live with L’s memory loss

This kind of learning essentially involved coming to terms with M’s old expectations of L’s memory functioning, which no longer applied. This required the emotional learning of patience as well as a number of skills that would help L.

The emotional learning of patience

Through the struggle of experiencing numerous situations of L’s memory loss, M first learned that he could not control or stop the exacerbation of her memory loss. Initially, he experienced this as extremely irritating and used the term nauseous to express his visceral, angry, and emotional reaction to what appeared to him as her endless repetitiveness by saying or doing something over and over as a result of her forgetfulness. His angry reaction manifested itself in an attempt to control her into being less forgetful. This was part of his caring burden, and at times, he needed respite from it, as his own health was suffering.

Coming to terms with L’s exacerbated memory loss involved a complex process of learning to be patient with L’s behavior. This involved a number of observations and key moments that were significant, such as the recognition that L would become worse and unsettled in response to M’s impatience. He was aware that his impatient response produced a downward spiral in which L would become more unsettled and confused; M would feel remorse and wanted to avoid this in future.

Another key moment was when he experienced the new insight that L did not realize or remember the extent to which her repetition was based on moment-to-moment memory loss. Once M realized this, he actively engaged in a process of testing and probing to see what L could and could not remember in particular circumstances. Previously, he would have intervened, but later he learned to let it take its course if harmless. This helped him respond in a more patient and kind way. He also learned patience through contact with a health professional, who helped him understand and normalize the nature and implications of L’s memory loss for her behavior, and by meeting other dementia sufferers at more advanced stages of memory loss.

The learning of complex skills

Through this process of complex emotional and behavioral learning, M developed some particular skills in responding to L’s memory loss that proved to be helpful. These included the following:

In essence, learning to respond to a loved one’s memory loss involves an extremely challenging process, a letting go of previous expectations and the learning of a patient openness that does not take continuity for granted.

The kind of knowledge generated by Phase 2 of this study was one of lifeworld depth. We went down from the breadth themes and could then illustrate how the narrative journey and identity were made up of more detailed textured experiences. These experiences were “opened” and revealed greater insight into the challenges, tasks, and living through of their complex structures.

The value of the depth phase

Rich and detailed texture. This addresses actual lifeworld occasions in which the complex journey is lived and opens the narrative into implicit but concrete events and situations that draw on descriptions of how particular phenomena were lived through. In our study, six significant kinds of experiences were alluded to from the breadth phase. They jumped out at us as asking for distinctive exploration in their own right. For example, the theme Something is wrong from Phase 1 opened up into highly textured components of Learning to live with L’s memory loss.

Transferable action. It is here, at this more detailed level of analysis, that useful transferable knowledge can be found, for example, how M became more patient and the kinds of skills he developed to help L cope with her memory loss. This level of focus is therefore not just about the empathic resonance (or empathic transferability) of what it is like but also about the more practice-orientated concern of what to do (actionable transferability). For example, in the essential structure of Learning to live with L’s memory loss (above), we learn more about how patience is learned in such situations, how humor is creatively used, and how a carer focuses on praising process in the loved one’s behavior rather than outcome. This knowledge is potentially instructive for others.

Limitation of the depth phase: Choosing “this” depth rather than “that”

In moving from breadth to depth, we concentrated on what appeared to be the most significant and compelling lived experiences suggested. This meant that we did not go down into other things. For example, although we explored new ways in which the couple found creative and appropriate ways to pursue an intimate relationship, we did not pursue examples of more everyday, less intense examples of taken-for-granted intimacy, such as sharing a new diet. In moving from breadth to depth, it is only the depth of certain things and not others, so some experiences that could be implicit to the broad, grand-tour phase were left unexplored. This might be inevitable in the light of Heidegger’s (1971) notion that in every “revealed,” there is a “concealed.”

In this section, we consider how the two methodological approaches produced two emphases in knowledge production that complement one another.

The generic phase was primarily concerned with sense-making breadth. It highlighted the narrative journey as a whole, as well as the nature of the self, or personal identity, that was active in making interpretive sense of that journey—what it meant to be such a carer. In our research, the carer’s emerging identity as the intimate mediator thus became clarified by this breadth focus.

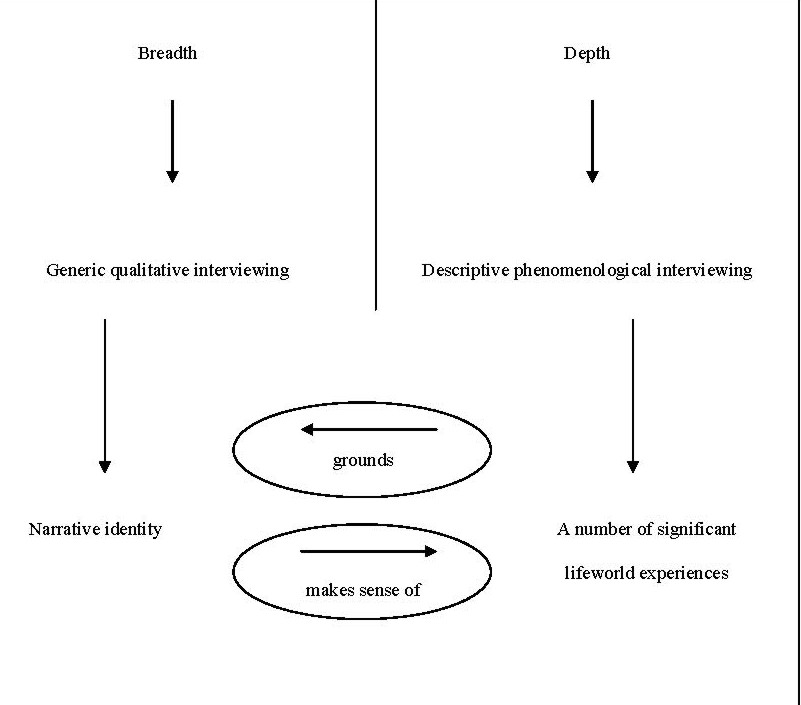

Figure 1. The complementarity of narrative breadth and lifeworld depth

The descriptive phenomenological phase was primarily concerned with lifeworld depth. It highlighted a number of compelling types of experience that were lived through, their details, textures, and meanings. Here it is possible to understand how such embodied experiences plunged the carer into multiple situations that constructed him. In our research, the learning of patience, together with each of the other six phenomena studied, such as changes in their emotional relationship and the transition to living apart, involved the description of rich, textured nuances and details that give insight into each of the multiple experiences that intimately affected his emerging identity and life experience.

The descriptive phenomenological phase was primarily concerned with lifeworld depth. It highlighted a number of compelling types of experience that were lived through, their details, textures, and meanings. Here it is possible to understand how such embodied experiences plunged the carer into multiple situations that constructed him. In our research, the learning of patience, together with each of the other six phenomena studied, such as changes in their emotional relationship and the transition to living apart, involved the description of rich, textured nuances and details that give insight into each of the multiple experiences that intimately affected his emerging identity and life experience.

We are not claiming in this article that to “do” depth, you have to do descriptive phenomenology. There are other possible ways to become more focused, both in interviewing and in other modes of data analysis. However, we are suggesting that a descriptive phenomenological approach is highly conducive to achieving what we have called lifeworld depth. This is because of two central features of this approach: First, it recommends an interview that begins with a request to the informant for a description in as much detail as possible of a concrete experience; and second, it involves a form of phenomenological analysis that goes back and forth between part meanings and whole meanings and stays very close to the specific narrative context (rather than coding meanings in more abstract ways). More than this, the value of a descriptive phenomenological approach in pursuing lifeworld depth is also its attendance to one of the implications of its coherent philosophical stance: that lifeworld experiences partially construct us—the depth of experiences that we live through are intimate to who we are. (See Holloway & Todres, 2003, for a discussion of flexibility and coherence in qualitative research.) This approach tempers a view that might overly emphasize human beings’ capacities to construct and reconstruct meanings from the “self” side. As a remedy to this potential overemphasis, the phenomenological philosophy that underpins its method acknowledges the phenomenon of co-constitution: how the relationship between self and world is reciprocal, with neither taking primacy in meaning making. Actively constructing and being constructed is the dialectic tension of lived experience and sense making, neither of which can be fully reduced to one another.

The complementarity of the two phases of the study expresses a circularity in which lived experience grounds narrative identity and narrative identity makes sense of lived experiences. Human living appears to be this kind of mutual circularity, in which we are always in the middle of attempting to make sense of our experiences, while living through the “flesh” of the experiences, which are beyond our construction and which, in a sense, construct us. As qualitative researchers in this study, we did not feel satisfied until we had given sufficient room for the phenomenon to show something of this breadth and depth.

Some versions of constructivism tend to overemphasize an individual or group’s agency in constructing an identity. However, the depth phase of this study indicates the extent to which the lifeworld, that is, what the person has lived through, provides the intimate substance for identity. Intricate complex experiences, such as withdrawing from previous social contacts, learning to respond to a loved one’s memory loss, and hard-won experiences of advocating on the loved one’s behalf, are all the intimate stuff of identity formation. The rich complexities of the lifeworld serve to ground identity. Some narrative approaches might neglect the power of the lifeworld as a form of being-in-the-world that is always in excess of our interpretations. On the other hand, people and groups still have some freedom to make sense of these experiences. Their sense of identity as a whole gathers up these different experiences, and there is a personal narrative struggle or “work” to fit these experiences together in a coherent way. This is the other direction of “being in the middle” of the dialectic of experience and sense making; in our study, the intimate mediator was active in this respect. Therefore, in this mutually interaffecting process, there is no lived experience alone or in itself, just as there is no identity construction or narrative alone or in itself without the food of lived experience.

This dialectical circularity of experience and sense making raises the possibility that a qualitative research approach could overemphasize personal agency, on one hand, or the deconstruction of the “subject” by the depth of experience, on the other.

The methodological approach of this study demonstrates one way of accounting for the kind of human engagement that has a measure of interpretive freedom in the way people live their lives but is also always grounded in experiences in excess of such freedom.

In conclusion, it could be said that the complementarity of the two phases of the study in revealing two kinds of knowledge product (narrative identity and lived-through experiences) finally demonstrates some support for a philosophical position that shows a person as both actor and sufferer, constructively making sense of narrative identity as well as being constructed by the experiences lived through; the substantive “more” of the lifeworld that always exceeds capture by interpretation.

Abramson, P. R. (1992). A case for case studies: An immigrant’s journal. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Fisher, A. (2002). Radical ecopsychology: Psychology in the service of life. New York: SUNY.

Galvin, K., Todres, L., & Richardson, M. (2005). The intimate mediator: A carer’s experience of Alzheimer’s. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 19, 2-11.

Giorgi, A. (1985). Phenomenology and psychological research. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Giorgi, A., & Giorgi, B. (2004). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In P. M. Camic, J. E. Rhodes, & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 243-274). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (APA).

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, language and thought (A. Hofstatder, Trans.). New York: Harper & Row.

Holloway, I., & Todres, L. (2003). The status of method: Flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 345-357. Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London: Sage.

Meier, P., & Pugh, E. J. (1986). The case study: A viable approach to clinical research. Research in Nursing and Health, 9, 195-202.

Merriam, S. J. (1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Miller, R. (2000). Researching life stories and family histories. London: Sage.

Platt, J. (1988). What can case studies do? Studies in Qualitative Methodology, 1, 2-23.

Todres, L. (2000). Writing phenomenological-psychological description: An illustration attempting to balance texture and Structure. Auto/Biography, 3(1/2), 41-48.

Todres, L. (2005). Clarifying the life-world: Descriptive phenomenology. In I. Holloway (Ed.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 104-124). Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

Todres, L., Galvin, K., & Richardson, M. (2005). Caring for a partner with Alzheimer’s: Intimacy, loss and the life that is possible. Unpublished manuscript.

Todres, L., & Holloway, I. (2004). Descriptive phenomenology: Life-world as evidence. In F. Rapport, (Ed.), New qualitative methodologies in health and social care research (pp. 79-98). London: Routledge.

| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (2) June 2005 |