| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (3) September 2005 |

The Evolution of Theory: A Case Study

Elizabeth D. Carlson, Joan C. Engebretson, and Robert M. Chamberlain

Elizabeth D. Carlson, DSN, MPH, RN, NP-C, Postdoctoral Fellow, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Division of Cancer Prevention, Houston

Joan Engebretson, DrPH, RN, Associate Professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Nursing

Robert M. Chamberlain, PhD, Director, Cancer Prevention Education and Teaching Program, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

Abstract: International attention is currently focused on alleviating health disparities through the adoption of new paradigms of research and the development of culturally relevant theories of health and illness. Yet, in spite of consistent calls to inform these deficiencies, the methodological trajectory from problem identification to theoretical development has remained relatively elusive. In this article, the authors present a case study of a systematic research methodology that resulted in a refined theory of social capital with practical relevance for health disparities research. Their purpose is to demonstrate how the stages and strategies of the hybrid model of concept development were extended as a research trajectory.

Keywords: hybrid model of concept development, qualitatively-derived theory, social capital, photovoice, health disparities

Citation

Carlson, E. D., Engebretson, J. C., & Chamberlain, R. M. (2004).The evolution of theory. A case study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(3), Article 2. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/4_3/html/carlson.htm

Author’s note

This study was supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute, Training Grant R25 CA57730.

Existing theories of individual health and behavioral change are inadequate for understanding or influencing population health inequalities (Emmons, 2000). For that reason, international attention has focused in recent years on alleviating health disparities by the adoption of new paradigms of research and the development of culturally relevant theories of health and illness. Concepts and theories focused at an ecological level, situating the individual within the context of the social environment, have been used only superficially, however, and are underdeveloped for meaningful research (Bachrach & Abeles, 2004). Furthermore, survey research and multilevel statistical modeling, using proxy measures of inadequately developed concepts, are not sufficient for the development of meaningful theories of explanation (Forbes & Wainwright, 2001; Oakes, 2004).

Although there have been consistent calls for basic social science research to inform these deficiencies, the methodological trajectory from problem identification to concept refinement to theoretical development has remained relatively elusive for the social sciences in general and health research in particular (Morse, 2004). Thus, our purpose in this article is to provide a case study of moving through this methodological trajectory to refine the concept of social capital for health disparities research. As a case study, this program of research involved the adoption of the stages and strategies of concept development suggested by Schwartz-Barcott and colleagues (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 1986, 2000; Schwartz-Barcott, Patterson, Lusardi, & Farmer, 2002). However, we demonstrate how we extended these stages and strategies as a systematic trajectory to develop a refined theory of social capital.

Evidence of racial and ethnic health disparities is consistent across a wide range of health outcomes and geographic settings (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2002). For instance, common explanations of poverty, access barriers, and lifestyle risk choices do not sufficiently account for the large cancer disparities between African Americans and Whites in risk, morbidity, or mortality (Ward et al., 2004). As a consequence, health researchers are moving from an individual focus to more ecological frameworks that situate the individual within the context of the social environment (Kawachi & Berkman, 2003). One concept that is receiving considerable interdisciplinary attention is social capital, defined as the quality of social relations embedded within community norms that facilitate cooperative behavior and improve quality of life (Coleman, 1990).

The phenomenal growth of interdisciplinary attention to social capital has developed from empirical research that suggests that communities with high social capital fare better than those with low social capital in terms of economic development, political efficacy, and health outcomes (Krishna, 2002; Putnam, 1993; Subramanian, Kim, & Kawachi, 2002). A recent Institute of Medicine report has suggested that the next generation of prevention research should seek to develop, implement, and evaluate interventions to increase social capital at the community level (Smedley & Syme, 2000). However, the lack of basic effort aimed at conceptual development has diminished the usefulness of social capital as a research variable and obscured the potential for health disparities work (Carlson & Chamberlain, 2003). In response, an ethnographic program of research was begun to refine the domains, attributes, and definitions of social capital.

The selection of social capital as a concept for study was based on the clinical experience of the first author (EDC), under the auspices of a community-campus partnership for health. Within this community-campus partnership, EDC had functioned in several roles: as clinical faculty for community nursing students, as a nurse practitioner in a geriatric practice, and as a doctoral student whose intentions were to engage the community in participatory action research. These various roles allowed her to interact with African Americans in their homes and in a health care setting, and with the leaders of one African American neighborhood in particular. As such, these experiences provided an opportunity to view health through multiple perspectives and multiple levels of influence. Her broader research interests focused on African American health disparities, and she was awarded a predoctoral fellowship from the National Cancer Institute. The second and third authors provided the guidance and analytical expertise essential to grasping the underlying significance of the social interactions as they unfolded.

As a framework for study, the stages and strategies of the hybrid model of concept development were adopted as a guide to the methodological trajectory. The hybrid model was originally proposed as a concept development method that moved beyond exclusive reliance on literature by explicitly incorporating clinical experience and field research methods (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 1986). The model was intended to identify, analyze, and refine concepts, in the initial stage of theory development, as a way to develop theories that had relevance for nursing practice. Field research methods were adopted from the social sciences and progressed through three stages: a theoretical stage, a fieldwork stage, and an analytic stage. With application, the authors revised the trajectory to suggest fieldwork in a setting different from the context of clinical practice (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 2000). Finally, the model incorporated three distinct fieldwork strategies (theoretical selectivity, theoretical integration, and theory creation) that would facilitate the link between concept refinement and theory development (Schwarz-Barcott, Patterson, et al., 2002).

It was a combination of these stages and strategies that provided the methodological framework for our research trajectory. As a case study, this article represents our attempt to reconstruct the series of events that began with a clinical problem; progressed through a period of concept selection, development, and refinement; and, finally, resulted in an explanatory theory of social capital with relevance for practice and research. This series of events occurred as a dynamic process that, at times, serendipitously pieced together a research trajectory. Consequently, relevant ethical considerations of informed consent and institutional approval were sought and granted during these events as appropriate.

For instance, the photovoice project in Neighborhood A was originally undertaken as a community-campus endeavor to engage community input. Nevertheless, we consulted the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston for clarification of ethical considerations prior to implementation. At the time, the committee determined that the project was not intended as research and, consequently, did not require informed consent. However, we obtained releases from all community resident photographers and photographed subjects prior to public display. These releases granted authority for distribution and publication of the photovoice display to the governing board of the community-campus partnership.

Later, during fieldwork, community and institutional approval was sought and granted for the retrospective analysis of the artifacts and products of this photovoice project. Later, fieldwork moved to prospective data collection, and community and institutional approval was granted as the research moved to Neighborhood B and finally to Neighborhood C. In addition, we used a Letter of Information as a means of informed consent for those individuals in Neighborhood C who participated in formal, audiotaped interviews. In this way, we addressed ethical considerations at each stage of the research in light of appropriate individual consent, community representation, and requisite institutional approval by The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

We chose the hybrid model as a methodological framework primarily because it explicitly incorporates experiential knowledge into the research design. This was particularly relevant because, at the time, there was no literature linking the concept of social capital to health disparities research. In addition, although epidemiologic research had shown a statistically significant association between social capital and health (Kawachi, Kennedy, & Glass, 1999; Kawachi, Kennedy, Lochner, & Prothrow-Stith, 1997), the association was statistically insignificant for the African American population. Furthermore, a number of public health practitioners were strongly advocating against the uncritical adoption of social capital as a focus for research or policy formation (Drevdahl, Kneipp, Canales, & Dorcy, 2001; Lynch, Due, Muntaner, & Smith, 2000). However, these findings and critiques were not congruent with the experience and observations of EDC. Thus, it was necessary to find a research framework that explicitly incorporated clinical experience into the research trajectory.

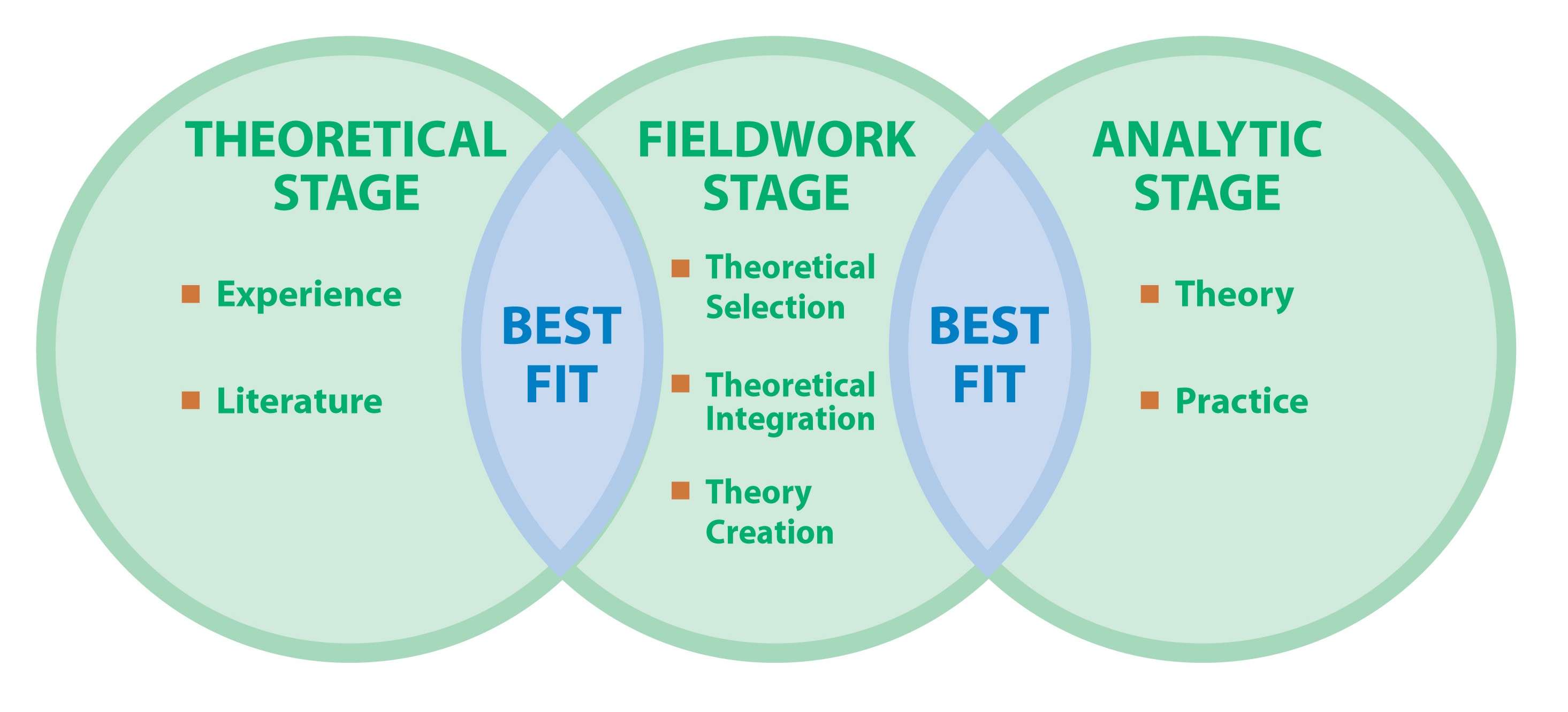

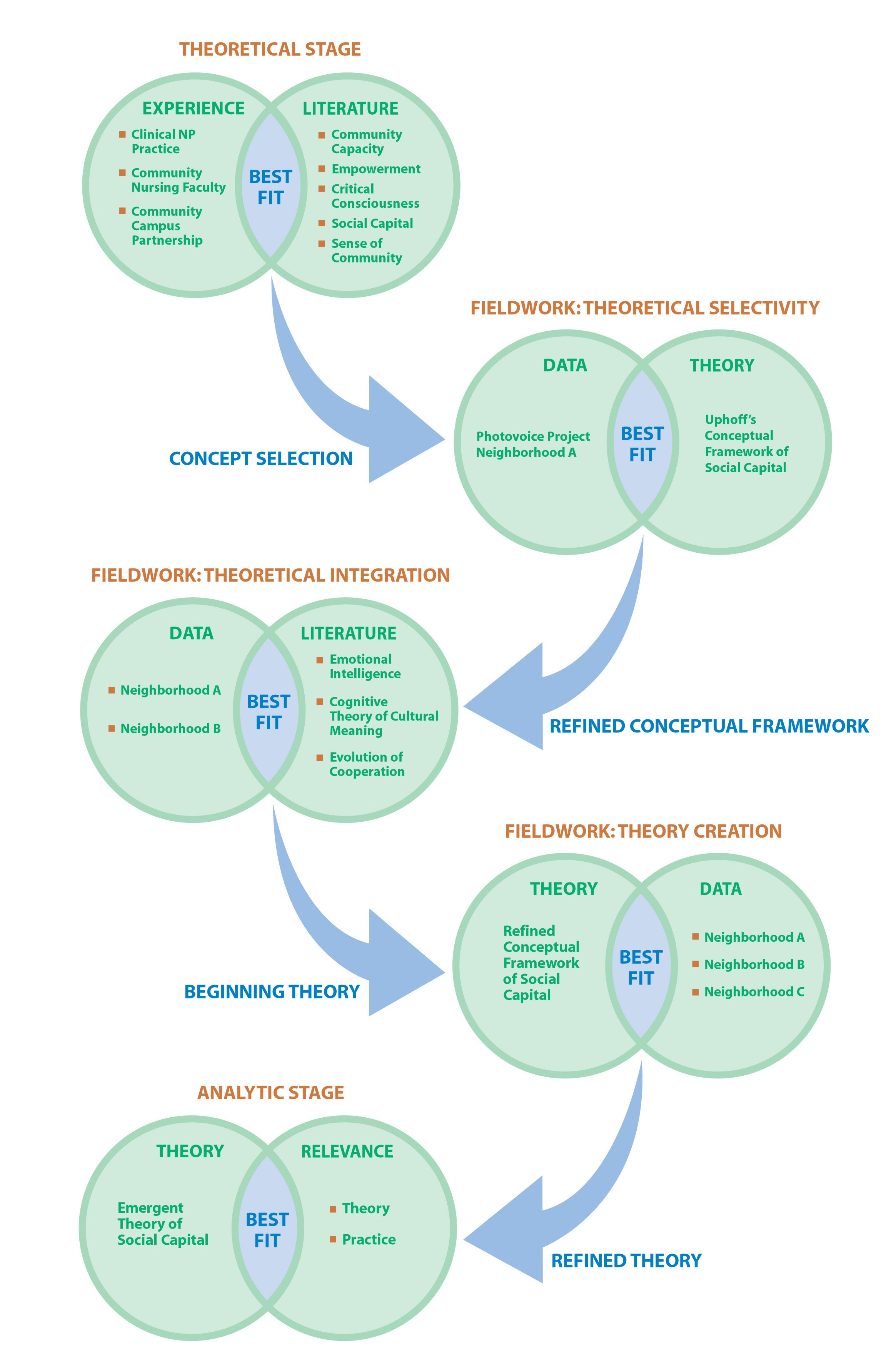

As the methodological framework, the hybrid model progresses through a series of three stages while continuously oriented toward discovery of the theoretical best fit within and between each stage of the research. Figure 1 represents a visual schematic of the stages and strategies of this research trajectory. As the first stage, the theoretical stage is oriented toward investigating existing concepts from the literature for the theoretical best fit with the problem identified through clinical experience. As the second stage, the fieldwork stage is oriented toward data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the findings with the theoretical best fit with existing theories from the literature. As the last stage, the analytical stage is oriented toward the application of the research findings in light of both existing theories and relevance to clinical practice. In other words, the trajectory begins and ends with application to clinical practice and continuously builds on existing literature to move to a more mature conceptualization of the phenomenon under study.

Figure 1. Methodological framework: Overall research trajectory depicting the three stages of the hybrid model and the essential elements within each stage

As such, this research trajectory was a dynamic, iterative, reflexive process that moved through the stages of problem identification, concept selection, concept development, beginning theory, and theoretical refinement. Although we attempt to convey some of the iterative processes and periods of reflection, the presentation of events requires a linear format. Furthermore, although we used the stages and strategies of the hybrid model as a methodological framework, the hybrid model was never intended as a cookbook approach to concept development. Rather, the authors of the hybrid model were attempting to describe the cognitive processes underlying each stage and the options inherent in social science research (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 2000). Similarly, we have attempted not to exemplify a precise method to be followed by others but, rather, to give a sense of the complexity involved and the variety of social science techniques that might be employed. As such, we begin with the presentation of the theoretical stage, an explicit period of time to investigate the theoretical best fit between experience and existing literature.

As such, this research trajectory was a dynamic, iterative, reflexive process that moved through the stages of problem identification, concept selection, concept development, beginning theory, and theoretical refinement. Although we attempt to convey some of the iterative processes and periods of reflection, the presentation of events requires a linear format. Furthermore, although we used the stages and strategies of the hybrid model as a methodological framework, the hybrid model was never intended as a cookbook approach to concept development. Rather, the authors of the hybrid model were attempting to describe the cognitive processes underlying each stage and the options inherent in social science research (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 2000). Similarly, we have attempted not to exemplify a precise method to be followed by others but, rather, to give a sense of the complexity involved and the variety of social science techniques that might be employed. As such, we begin with the presentation of the theoretical stage, an explicit period of time to investigate the theoretical best fit between experience and existing literature.

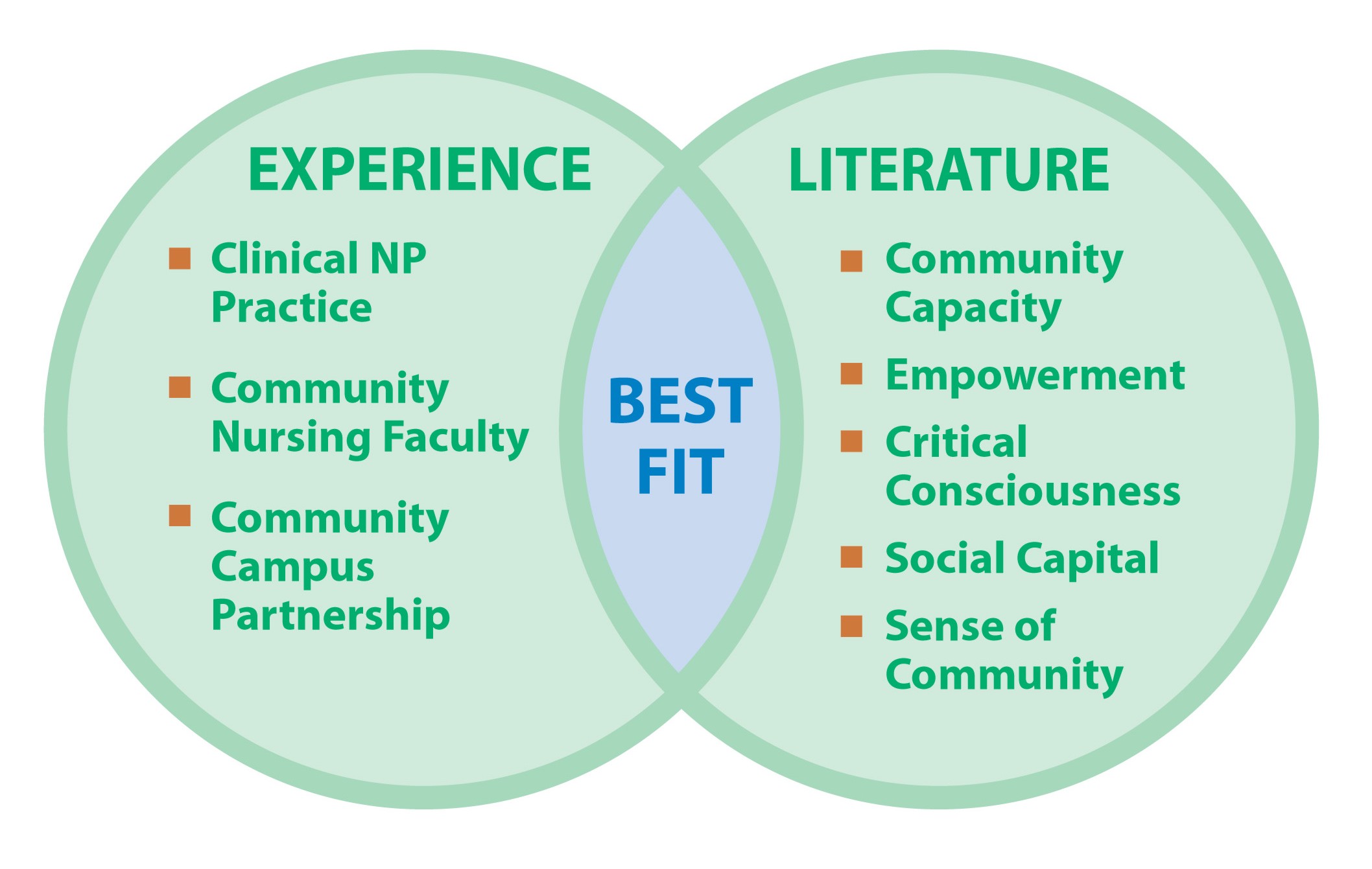

To reiterate, the theoretical stage is oriented toward the investigation of diverse concepts for theoretical best fit with a relevant problem identified through clinical experience. As the first stage in the trajectory, the phenomenon of interest frames the selection of relevant concepts for exploration. As such, this theoretical stage is a time for developing a foundational understanding of the phenomena of interest and a beginning literature search for appropriate concepts (Schwarz-Barcott & Kim, 2000). This requires a broad systematic interdisciplinary search to understand the meanings of the concepts, how they have been used, and how they have been measured. Thus, at this stage, the researcher attempts to find the best fit between experiential knowledge and existing concepts. Figure 2 is a visual representation of this theoretical stage. The end product of this stage is the selection of a concept that best fits experience, along with a loose working definition, for further exploration during the fieldwork stage. In this presentation, the trajectory of experiential events is presented separately from the trajectory of concept exploration, although in reality, these trajectories occurred simultaneously and continually informed one another.

Figure 2: Theoretical stage of the hybrid model: During this stage, issues of concern identified from clinical experience are examined for congruence and best fit with existing concepts drawn from the literature.

As the context for experiential insight, Neighborhood A is a low socioeconomic, African American neighborhood of approximately 38,000, nested within a large metropolitan urban city. In this neighborhood, the effects of concentrated poverty are ubiquitous. For instance, 30% of families live below the national poverty level, 41% of the population is employed in low-paying jobs, and 32% of those over the age of 25 have less than a high school education. Despite the poverty level, the university had initiated a partnership with this particular geographic neighborhood because of the community’s reputation for having a highly organized and politically astute civic infrastructure (Kawachi et al., 1997).

However, after 3 years of working in the community and participating in the community-campus partnership, the first author was increasingly aware of a conundrum. There was a disconnection between the reputation of the community from the university’s perspective and the inability of community leaders to engage residents in civic participation or move forward on community health projects. This disconnection sparked interest in the concept of social capital, a fairly recent concept to the public health literature, as EDC entered a doctoral program in nursing. Social capital, defined in public health literature, encompassed the features of social organization such as norms of trust, reciprocity, and civic participation that facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit and improve quality of life.

In an effort to facilitate interest and participation in participatory research, EDC introduced the idea of a photovoice project to the community-campus partnership. Photovoice is a participatory health promotion strategy of engaging participants in narrating community issues through photographs and stories (Wang & Burris, 1997). The idea is based on the theoretical work of Freire (1970/2000), a Brazilian educator who used participatory strategies to engage adult learners. Freire proposed an approach to learning that engaged the learner and the teacher as cocreators of knowledge through a process of listening, dialogue, action, and reflection. This process is foundational to many public health concepts such as empowerment, critical consciousness, and participatory research.

The community-campus governing board and the neighborhood civic association approved the photovoice project, and the campus institutional review board was consulted for guidance. The goal of the project was to document community health concerns through storytelling and photography. The objective was to engage community residents in a group dialogue process. This dialogue was intended to act as a catalyst to develop a shared vision and prioritized agenda to improve the health of the community. EDC found a group facilitator who had a background in both the dynamics of group process dialogue and the use of storytelling as a communication strategy (Simmons, 1999, 2001). The project was implemented with the empowerment philosophies of community ownership; the citizens’ council and members of the partnership board were consulted for direction, advice, and approval at all stages of project implementation.

In August 2000, we launched the photovoice project with the first of four 8-hour workday sessions. On the first workday, we introduced and practiced the concept of storytelling as a way of discovering knowledge, influencing others, and creating change. During this workday, critical comments from participants reflected the lack of trust and reciprocity within the community. These comments also suggested that the norms of community relationships suffered from low, or even negative, levels of social capital. For example,

Where my brother-in-law lives, people help each other but here, if you do that, people get mad. Me and my brother tried to pick up around the neighbor’s house and people got mad at us.

You see people who want to do something but if you mention it they say, “Why don’t you do it?” but one person can’t do it all by himself.

The group of participants reconvened 5 weeks later for the second 8-hour workday. The workday was intended to engage the group in critical reflection directed at community issues. Each participant brought one or two 8-by-10-inch photographs, and the accompanying stories were presented individually to the group and displayed around the room during the dialogue session. The majority of the photographs and stories reflected the community members’ despair and feelings of being powerless to improve their social conditions. However, the experience of participating in the photovoice project not only engaged individuals but also appeared to influence the level of trust and initiative within the group. There was a new level of enthusiasm observed in both the individuals who participated in the photovoice project and the governing board of the community-campus partnership.

It appeared that the photovoice project had been the catalyst for increasing the community’s stock of social capital by increasing trust and civic participation for collective action. For example, 3 of the photovoice participants joined the community-campus partnership, and the meetings became lively, honest discussions attended by all board members instead of the usual two or three. Two of the participants used Lego building blocks to build a model of their vision for a new community center and presented this to the group. Other participants talked of joining their community civic clubs and of individual intentions to make the community a better place in which to live. Personal reflections indicated a new sense of personal responsibility:

This has been a mirror to see ourselves. Now it is up to us to do the rest.

This has totally changed my life. Now I have a sense of duty, a part to play.

EDC recorded these observations and conversations in a personal journal.

However, the initial burst of enthusiasm, engagement, and participation was still inadequate to move the group forward to a plan of action. In December 2000, arrangements were made for the group facilitator to return for a third workday. This workday helped the group form a vision for a healthy community and a prioritized action plan, yet even with a vision and plan of action, the group was still unable to move forward on implementation. With community approval, the group facilitator was brought back in March 2001 to lead a fourth workshop. This workshop focused on leadership styles, skills, and decision making, but again, the group was unable to move forward with decision making or resource mobilization.

In November 2001, still intent on the philosophy and goals of participatory research, EDC helped make arrangements for a delegation of community residents to visit a community-based program in a distant city. This program appeared to have potential as a vehicle for implementing several community objectives. The program was known as the Living at Home–Block Nurse Program (LAH-BNP) and was based on a philosophy of neighbors helping neighbors. The program had a successful 20-year history in Minnesota and was being expanded to the resident state. The delegation visited the site of one successful program in a community that was demographically similar to theirs: low income, urban, and predominantly African American.

The delegation group felt that the LAH-BNP met several goals for a healthy community and could theoretically enhance the neighborhood’s stock of social capital. Key features included reliance on a volunteer base of neighbors helping neighbors, an umbrella organization that provided technical support, the opportunity to develop organizational skills and capacities, and access to significant start-up funds. The delegation group and community members embarked on plans to implement the program but abandoned the project within a few months. Conflicting interpretations over issues of decision making, responsibility, and communication quickly escalated into an antagonistic environment filled with anxiety, suspicion, and fear. After 6 years of building trust and good working relations, all of the individuals involved discarded any intentions to proceed with the project or participatory research amid accusations of racial insensitivity and exploitation.

During this same period, EDC conducted an extensive literature search in an effort to understand the relationships among community-oriented concepts such as empowerment, critical consciousness, sense of community, community capacity, social capital, and community cohesion. She explored each of these theoretical concepts exhaustively for “theoretical fit” with experiential insights. In fact, a recent symposium of community experts had listed all of these community-oriented concepts, including social capital, as essential attributes for building community capacity (Goodman et al., 1998), yet the list provided no underlying theory of how to put these attributes to work for community change or what to do if these attributes were lacking. In effect, the theoretical investigation had revealed that all of these concepts were poorly defined, conceptually underdeveloped, and inadequate for understanding or explaining the social dynamics occurring in Neighborhood A.

For instance, although the photovoice participants had overwhelmingly expressed a “sense of community,” it was not enough to overcome the despair and apathy of hopelessness. In addition, although the photovoice project had as a purpose to engage and empower community members, this transformation of “empowerment” had unforeseen consequences. In effect, several individuals had transformed to attitudes and behaviors that exemplified domination and control over others. At the same time, the enthusiasm and participation that occurred by raising “critical consciousness” was left dormant by the inability of the group to facilitate effective cooperative action. Thus, the experiential knowledge base had incorporated several lines of theoretical investigation for analysis and best fit, yet none of the community-oriented concepts had the conceptual maturity, boundary delineation, or established empirical support to make them useful for research purposes (Morse, Hupcey, Penrod, & Mitcham, 2002).

Meanwhile, the concept of social capital was increasingly being used as a variable in public health research. However, a literature synthesis during the summer of 2002 revealed that there had still been little effort directed toward concept development (Carlson & Chamberlain, 2003). This deficit had resulted in (a) the lack of distinction on whether social capital was an attribute of a place or an individual, (b) the problematic use of operational variables, and (c) limited theoretical exploration of causal linkages. These deficits had also masked the evidence that might support the hypothesis generated by the photovoice project: that the concept was useful and necessary for public health practice and health disparities research. EDC approached the fieldwork stage with a working definition of social capital as the quality of the social relations embedded within community norms that facilitate cooperative behavior and improve quality of life.

The second stage of the hybrid model, the fieldwork stage, is oriented toward finding the theoretical best fit between the data generated from ethnographic field research and existing theoretical literature. As such, this stage is intended to corroborate and refine the selected concept by moving to fieldwork methods to generate and analyze data. Traditionally, these fieldwork methods were used to study the course of everyday interactions among a group of individuals in their natural environments. Fieldwork methods emphasize participant observation over extended periods of time in the fieldwork setting. Within this fieldwork stage, Schwartz-Barcott, Patterson, and colleagues (2002) have detailed three distinct strategies for linking concept development to theory construction. These three strategies are theoretical selectivity, theoretical integration, and theory creation, and each strategy is focused on the generation and analysis of data toward a specific purpose. In our research design, we used these three strategies in sequence to move from the retrospective analysis of events from Neighborhood A to prospective data collection in both Neighborhood B and Neighborhood C.

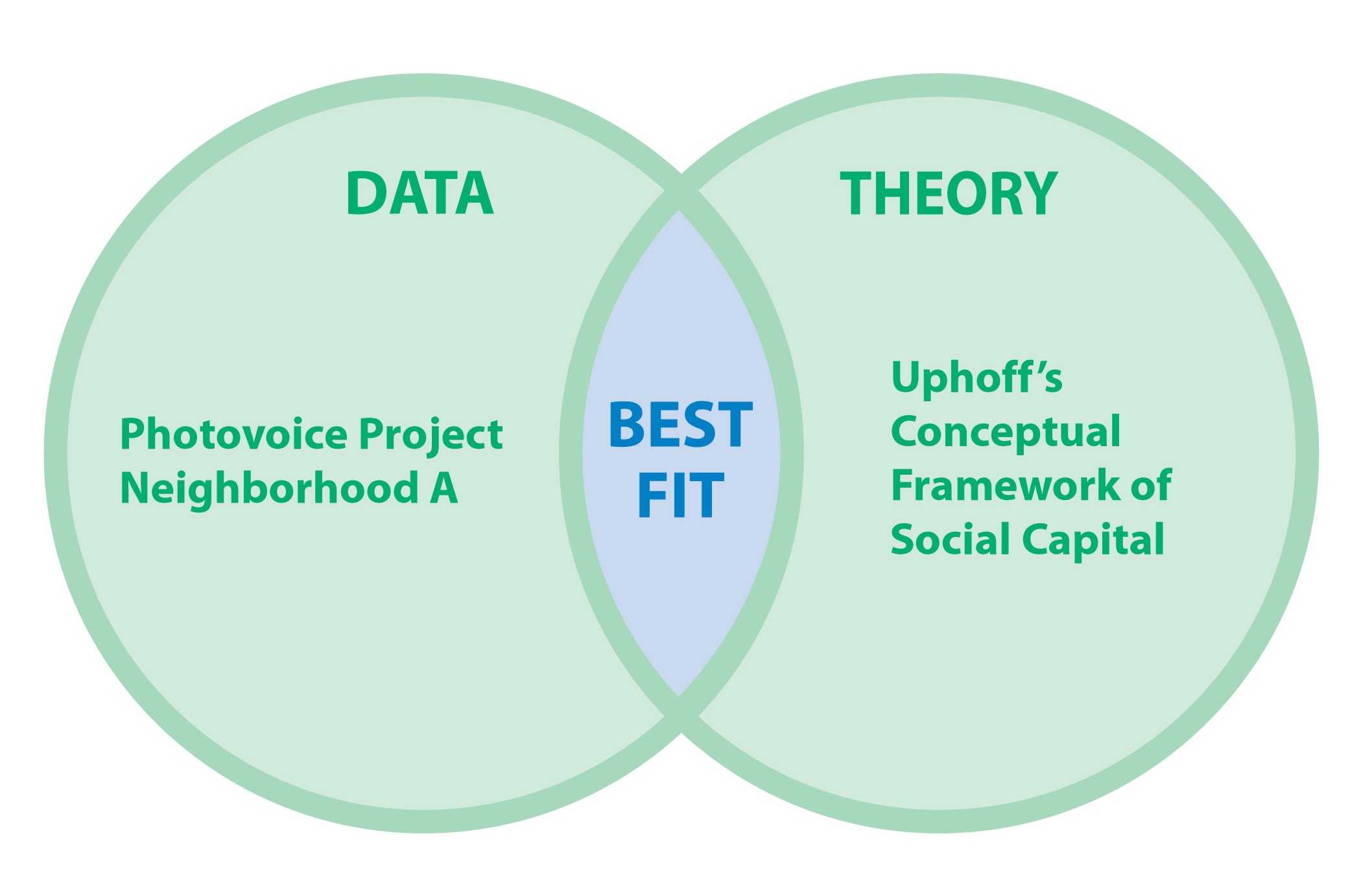

Having tentatively identified social capital as a relevant concept for further development, we moved to the fieldwork stage of the hybrid model and the strategy of theoretical selectivity. The purpose of this strategy is to select the theoretical best fit with an existing conceptual framework drawn from the literature. The end product of this stage is the selection of an analytical lens to shape further data collection and analysis. To accomplish the goals of this stage, we used the existing products from the photovoice project (photographs, stories, journals, and e-mails) for a retrospective qualitative analysis of the content and themes. In this section, we describe how we analyzed the photovoice data and how we selected an existing social capital framework as the best theoretical fit with the findings of the retrospective analysis of Neighborhood A. Figure 3 is a visual representation of the theoretical selectivity strategy.

Figure 3. Theoretical selectivity strategy used during the fieldwork stage of the hybrid model. During this phase, the findings from the retrospective analysis of the photovoice experience are examined for congruence and best fit with an existing conceptual framework of social capital that has been drawn from the literature.

During the spring of 2002, EDC used the data generated through the photovoice project for a pilot study. This ethnographic pilot study included as data the (a) photographs and stories from community participants, (b) dialogue notes from the group sessions, and (c) journal entries from EDC and the group facilitator, as well as all e-mail correspondence between the two. Although we approached the data with an analytic lens attuned to the concept of social capital, we oriented the thematic analysis toward inductively summarizing data into categories and themes. One thematic category exemplified the disconnection between community aspirations and the behaviors that inhibited their inability to improve the community. This category of findings was labeled cognitive-behavioral disconnection.

Returning to the literature, EDC found a conceptual framework of social capital that also identified cognitive and behavioral domains (Uphoff, 2000). Uphoff, a professor of government at Cornell University and director of the Rural Development Participation Project from 1977 to 1985, had written extensively about his experiences with 69 villages in rural India. As a result of these experiences, he had analyzed what did and did not work with regard to participatory development efforts (Uphoff, Esman, & Krishna, 1998). His interest in the concept of social capital came from his observations that there was an association between desirable community development outcomes and certain kinds of values and norms. His insights resulted in an expanded conceptual framework of social capital that moved beyond the concepts of trust, reciprocity, and participation. Although Uphoff’s framework had been tested empirically, the survey instrument was specific to the cultural features of rural India villages and inappropriate for the United States (Krishna & Uphoff, 1999). However, the theoretical appeal of the framework came from the distinction between a cognitive and structural domain that fit with the analysis of the pilot data.

For instance, in Uphoff’s (2000) framework, the cognitive domain encompassed the values, norms, attitudes, and beliefs surrounding the attributes of trust, reciprocity, solidarity, cooperation, and generosity. Uphoff suggested that although these values, norms, attitudes, and beliefs always reside in individual thought processes, there is also a significant collective component. In contrast, the structural domain encompassed observable group behaviors that supported collective action such as decision making, communication patterns, resource mobilization, and conflict management. Uphoff suggested that the cognitive and structural domains were connected by expectations and resulted in the outcome variable for social capital: mutually beneficial collective action (MBCA). EDC began work to develop a dissertation proposal with the intended purpose of refining the concept of social capital for scientific investigation. The specific aim was to explore the social dynamics of a community that had successfully demonstrated their ability to mobilize MBCA using Uphoff’s social capital framework as an analytical lens.

EDC developed a codebook that represented all of the categorical elements of Uphoff’s (2000) framework. However, Uphoff used terms such as norm, value, attitude, and belief without defining exactly what he meant by these. Because a codebook must contain terms that are defined precisely in a mutually exclusive manner, EDC adopted definitions for these terms from the American Heritage College Dictionary (American Heritage Dictionaries, 1997). Each element of the social capital framework was delineated, defined, and visually displayed as a schematic coding system. In addition to coding categories, it was necessary to define how the textual data would be reduced. The decision was made to adopt a cognitive meaning approach to textual data reduction (Lofland & Lofland, 1995). This entailed selecting a phrase, sentence, or paragraph (i.e., a portion of text) that defined, interpreted, or justified an individual’s view of reality. These units of analysis were further delineated, based on relevant literature (Watts, Griffith, & Abdul-Adil, 1999), as perceptions, interpretations, inferences, or justifications. Because behavioral and affective changes were seen in the aftermath of the photovoice project, behavior and affect were designated as secondary units of analysis. These were designated as secondary units because some initial experimentation with the coding system showed that behavior and affect were always embedded within the primary cognitive unit of analysis. As a next step, the photovoice data were then reanalyzed using the codebook.

The results of this analysis provided new insights into the social dynamics operating in the community. However, the development of a poster presentation revealed some conceptual problems. For instance, although Uphoff (2000) placed trust and reciprocity into one category under the cognitive domain, analysis of the photovoice data revealed that it was the high level of distrust that was destructive to all the other elements needed for cooperative behavior. Although Uphoff’s model had designated values, attitudes, beliefs, and norms as variables of each attribute category, there was a disjunction within category types. For example, cooperation was valued by community members but seldom seen in their attitudes, beliefs, or norms. Generosity was valued, but the pervasive distrust undermined generous behavior by keeping residents isolated out of fear. Solidarity was valued but acted on only when there seemed to be an external threat. Furthermore, this type of solidarity produced a destructive “us against them” stance that further isolated the community from the resources of the larger society. In addition, although communication patterns were characterized as didactic (talking at each other with little listening), these communication patterns affected decision making, resource mobilization, and conflict management strategies. Consequently, EDC was redirected back to the literature to make sense of these discrepancies before moving on to the next phase of fieldwork in a different contextual setting.

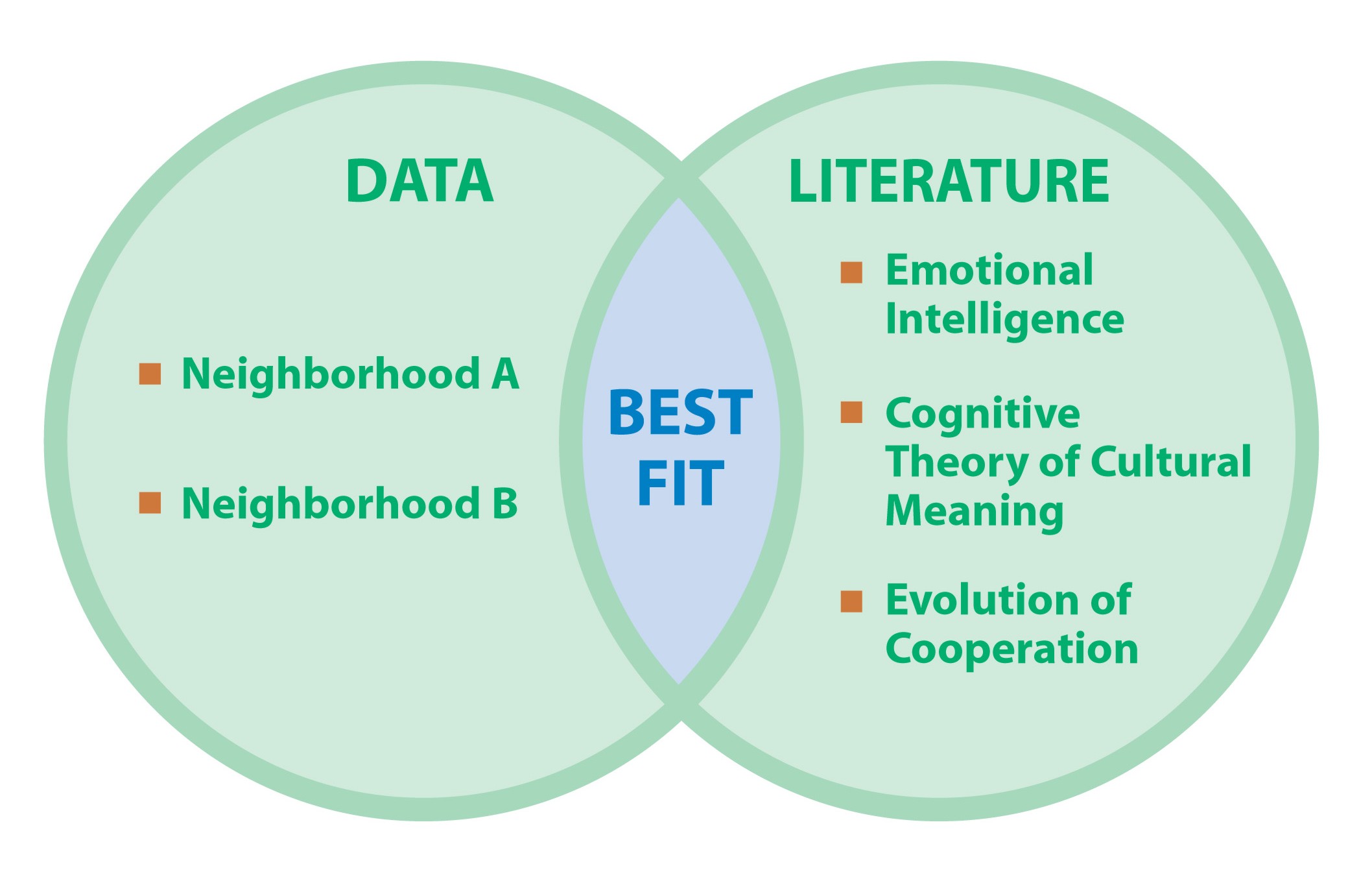

As another fieldwork strategy, theoretical integration has as its purpose to search for the theoretical best fit between findings generated through fieldwork investigation and insights gleaned from the literature. The purpose of this strategy is to explore and evaluate the adequacy of the selected analytical framework against data generated in a different fieldwork setting. In addition, these findings are interfaced with existing literature for theoretical best fit and explanatory understanding. During this phase, the research shifts to issues of how and why, and the inquiry moves to deeper questions of explanation. The end product of this stage is a beginning theory and new analytical lenses. Figure 4 is a visual representation of the theoretical integration phase of our research trajectory.

Figure 4. Theoretical integration strategy used during the fieldwork stage of the hybrid model. During this phase, data generated from both neighborhood settings are examined for congruence and best fit with existing theories of explanation that have been drawn from the literature.

For the next stage of fieldwork, we chose a setting based on a strategy of selecting a contrasting case to Neighborhood A: a community that had successfully demonstrated its ability to mobilize MBCA. For the purposes of the study, MBCA was defined as the ability to implement and sustain a Living at Home–Block Nurse Program. This was in contrast to the unsuccessful attempt to implement an LAH-BNP by Neighborhood A. The same African American community that the Neighborhood A delegation had visited was chosen as an appropriate site. Although this community had a smaller population (approximately 14,000), it also encompassed approximately 5 square miles of an urban geography and was predominantly African American (93%), with more than 33% of the households living below the poverty level. EDC began to negotiate entry into the field site through the umbrella organization of the LAH-BNP.

However, while we were negotiating entry and obtaining institutional approval, it became increasingly apparent to us that Neighborhood B had little investment in the LAH-BNP except as service recipients. Although all board members, staff, and volunteers were African American, they came from outside the community, and the White community coach had obtained all program funding. In essence, the program’s success was dependent on outside facilitators, and there had been little community capacity developed. In addition, as the nation’s economy slumped and financial resources diminished, relationships between the African American board and the White umbrella organization became increasingly volatile and hostile. Again, conflicting interpretations over issues of decision making, responsibility, and communication quickly escalated into an environment filled with suspicion, fear, and hostility. The African American LAH-BNP board terminated all relationships with the umbrella organization with threats of legal action and accusations of racial exploitation. Fieldwork would be impossible and inappropriate to conduct in this environment.

However, the similarities between the Black-White relationships in Neighborhood A and those in Neighborhood B were too great to dismiss as coincidental. Both had histories of 5 or 6 years of productive Black-White relationships, but both had quickly erupted into hostile environments of racial conflict over misunderstandings, unsubstantiated assumptions, and issues of distrust. The interpretations of events from both perspectives—in both communities—indicated that there had to be a strong cultural component at work. EDC delved back into theoretical literature to look for new insight and theoretical linkages to understand the implications of culture (Carlson & Chamberlain, 2004). In addition, this theoretical immersion produced several new lines of investigation.

For instance, Brown (1998) provided a relevant definition of culture as the characteristic patterns of thought and behavior among a group based on shared social experiences. Understood in this way, Uphoff’s (2000) norms could be characterized as cultural patterns of thought (cognitive domain) and behavior (structural domain). Exploration of the cultural phenomenon led to Strauss and Quinn’s (1997) theories of cognition and cultural meaning. Along these same lines, EDC explored social identity theory to understand solidarity and group behavior (Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 1999). Although social identity theory provided a useful explanation of the us-against-them phenomenon, the literature on organizational theory provided a better explanation of effective and ineffective group functioning (Druskat & Wolff, 2001). An exploration of cooperation as an evolutionary trait was examined for relevance (Ridley, 1996). This literature suggested that the most productive approach to cooperation anticipated human errors and required forgiveness as an essential ingredient. In addition, an in-depth analysis of trust (Hupcey, Penrod, Morse, & Mitcham, 2001) provided a refined framework for understanding this attribute of social capital. We incorporated all of these theoretical lenses as we reconfigured the conceptual model.

The visual reconfiguration started with the cognitive domain, which was reaggregated around the more abstract categories of values, attitudes, and beliefs. Under each of these, Uphoff’s (2000) concepts of trust, reciprocity, solidarity, generosity, and cooperation were retained. However, by doing this visual reconfiguration, we distinguished trust as a concept separate from trustworthiness and moved it to a central position. Assumptions embedded in the norms of trustworthiness, solidarity, generosity, and cooperation were now placed as antecedent, or preceding, contributors to the concept called trust. In the same manner, the structural domain was reconfigured around bonding-level, group-level, and bridging-level interactions based on organizational theory that aligned well with the social capital literature (Druskat & Wolff, 2001; Saegert, Thompson, & Warren, 2001).

We developed a table matrix for each level of social interaction that dichotomized a measurement variable of either constructive or destructive manifestations. For instance, we outlined norms of communication according to whether they were constructive or destructive to the development of trust. Thus, this construction of a measurement variable was congruent with the analytical strategy of developing theoretical polar opposites (Lofland & Lofland, 1995). Although these polar opposites represented hypothetical extremes on a measurement continuum, they provided a basis for analyzing the fittingness of the emerging theory with the fieldwork data to be collected. In addition, the outcome indicator of social capital was now changed to the efficacy of MBCA. This theoretical change moved MBCA from a dichotomized measure to a continuum of group effectiveness in achieving goals and objectives.

The visual rearrangement became the basis for revisions to the codebook. These revisions helped clarify why the original primary and secondary units of analysis had not functioned well during analysis of the photovoice data. For example, it had been difficult to distinguish between perceptions, interpretations, inferences, and justifications. However, by incorporating the ideas of culture and interpretation of meaning, it became evident that there was no individual perception without interpretation of meaning, no individual inference without an interpretation of meaning; and no individual justification that was not an interpretation of meaning (Strauss & Quinn, 1997). Furthermore, the reason that the secondary units of analysis—behavior and affect—were always embedded in the cognitive meaning also became evident. Behavior and affect were responses to the internal and external stimuli created by an individual’s interpretation of meaning. Consequently, the unit of analysis was reduced to a linguistic unit of text that made up an individual’s interpretation of reality. We then redirected the research question toward exploring the fittingness of the new conceptual framework with data from a new fieldwork setting.

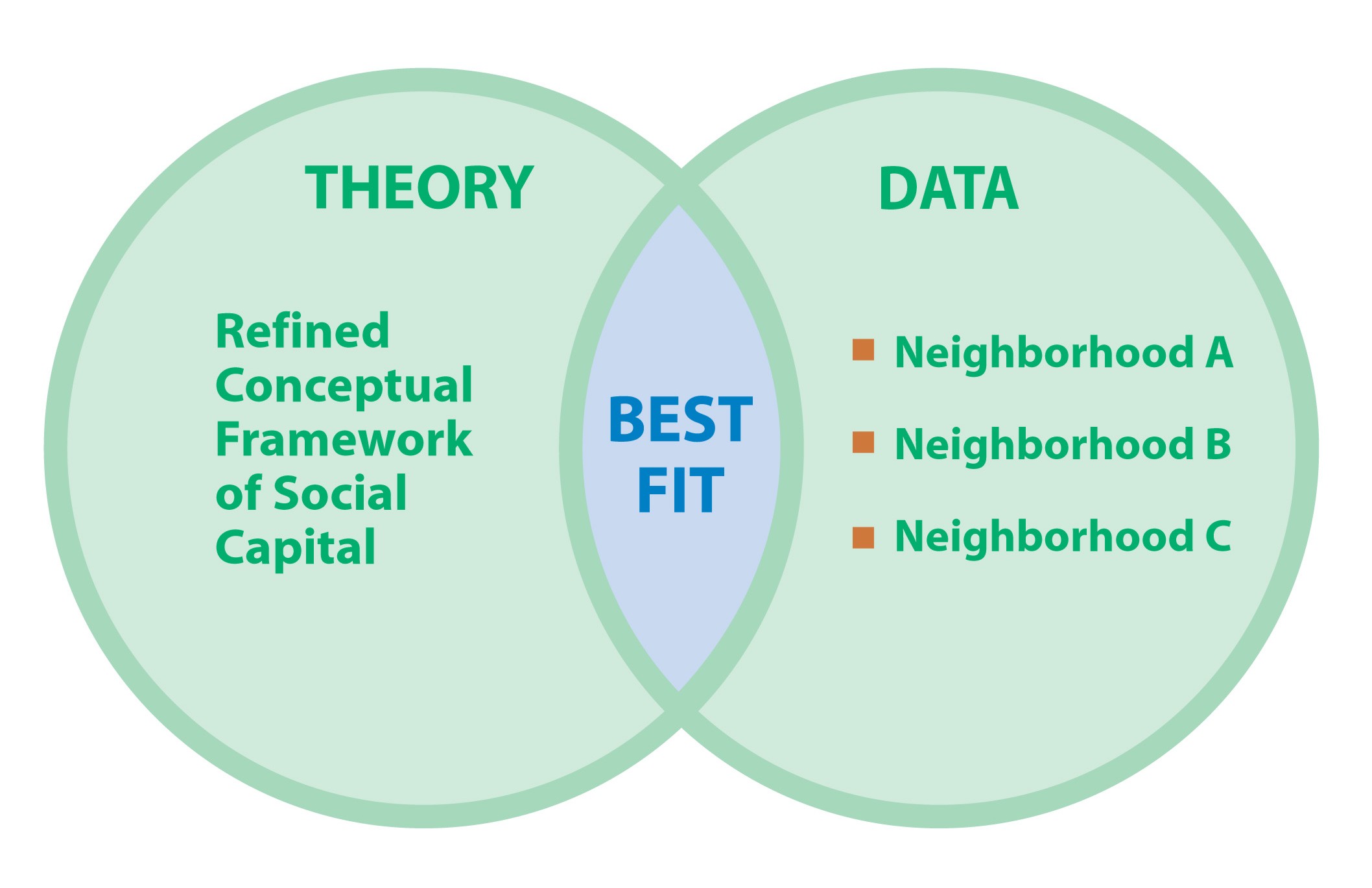

We adopted the theory creation strategy as the final phase of fieldwork. The purpose of the theory creation strategy is to continue to develop the theoretical best fit between the emergent theory and findings from the data. The focus of this strategy is on describing the essence of the phenomenon, identifying influencing factors, and creating relational statements (Schwartz-Barcott, Patterson, et al., 2002). At this point, the research project has gone through several phases, and the conceptual model has already moved through many refinements. The end product of this stage is a refined theory of the phenomenon of study. Figure 5 is a visual representation of how we incorporated the theory creation strategy into the research trajectory.

Figure 5. Theory creation strategy used during the fieldwork stage of the hybrid model. During this phase, the refined conceptual framework of social capital is examined for congruence and best fit with the convergence of data generated from all three neighborhood settings.

A third site was selected for fieldwork, again based on the strategy of a investigating a contrasting case. Once more, we selected a contrasting community based on its ability to mobilize MBCA by implementing and sustaining the LAH-BNP. The selected fieldwork site was rural and predominantly White, with a population of approximately 10,000 within the city boundaries. However, the program served a much larger geographic area encompassing 200 square miles (5,180 square km) and approximately 40,000 individuals. Although the overall poverty rate for the town was only 7%, the poverty rate rose to 23% for adults over the age of 65 who lived within the larger program boundaries. Unlike the LAH-BNP in neighborhood B, all staff, board members, and volunteers lived in the community, and their funding came through the direct efforts of the board members. A sampling plan was used to identify purposefully participants within the community who could comment thoughtfully on the community at large, the efficacy of the LAH-BNP, and the efficacy of various organizational groups within the community. As such, we also used this sampling strategy to search for contrasting examples of group efficacy within the community.

As an ethnographic participant observer, EDC lived in Neighborhood C for 2 weeks during the summer of 2003. Ethnographic data collection consisted of field notes of observations, formal and informal interviews, and investigation of public documents and artifacts. As the data were collected, transcribed, coded, and analyzed, theoretical fittingness with the reconfigured model emerged. The analysis was directed at identifying influential factors, creating relational statements, and checking and validating interpretations in light of the emerging data and previous phases of research. As we analyzed the data, it was evident that the reconfigured model could define and account for all elements of the model and the relationships among them. EDC discussed the fit and relevance of the emergent theory with members of Neighborhood C, with an expert in emotional intelligence, and with faculty advisors who represented the disciplines of anthropology, sociology, public health, and community health nursing. In the final analysis, it was necessary to make only one conceptual change to the model. The concept of solidarity as a function of group membership was replaced with the concept of unity as a function of respect and responsibility for self, others, and the environment that sustains all.

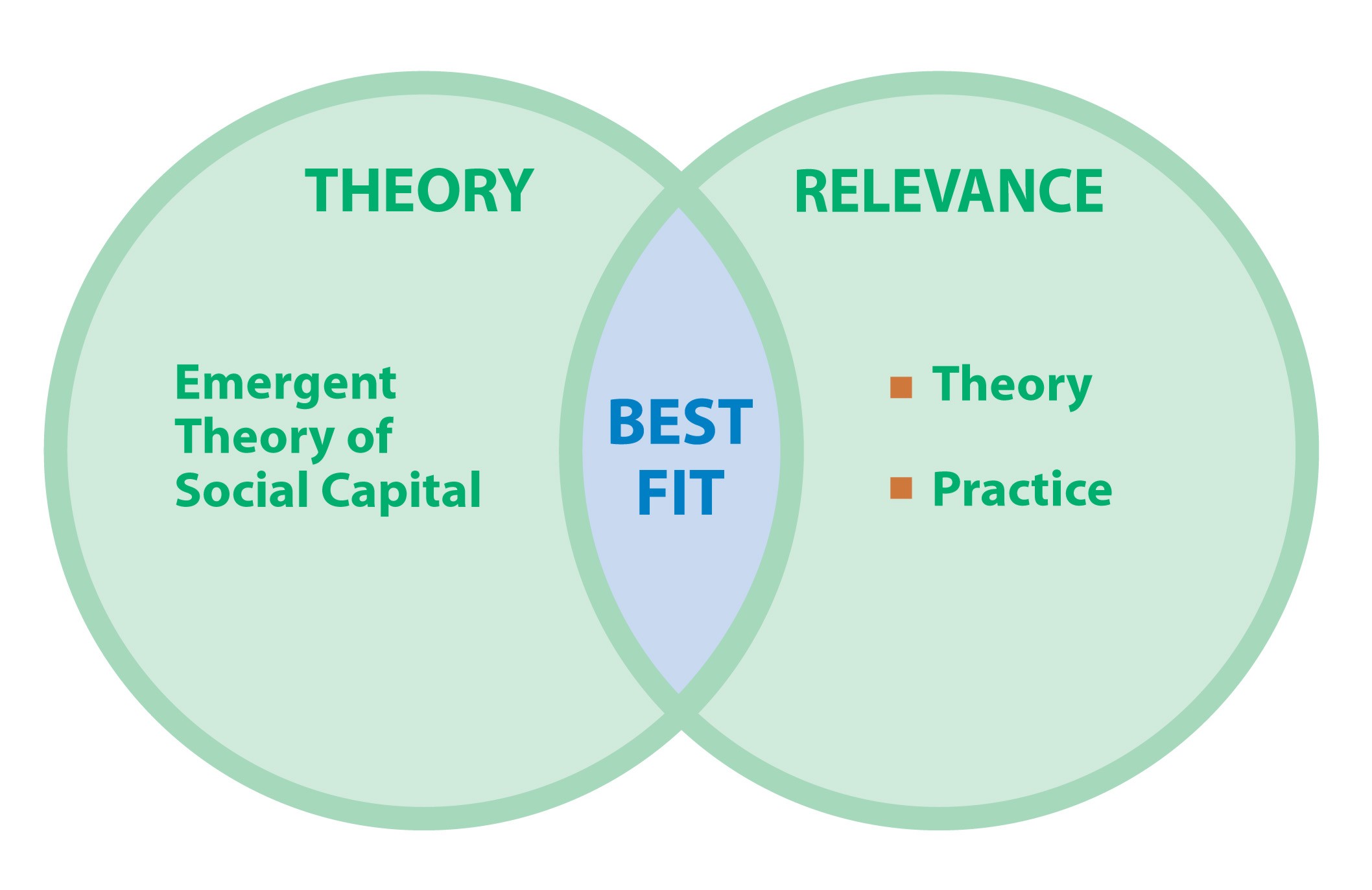

As the final stage of the hybrid model, the analytic stage is meant as a time for reflection after fieldwork is finished. During this time, the researcher can review the findings of the study within the context of past and future theory development and the within the context of research and practice agendas. Thus, specifying this period as a distinct stage provides an opportunity to make explicit the implications of the findings for closing existing gaps between theory and practice. However, because our focus here is on the process of discovery, not the emergent theory as product, an in-depth discussion of the emergent theory is beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, we attempt to provide a brief overview of potential implications in an effort to continue the focus on the process of discovery outlined by the hybrid model. The end products of this stage are the implications for future research and hypothesis testing. Figure 6 is a visual representation of how we incorporated the analytic stage into our research trajectory.

Figure 6. Analytic stage of the hybrid model of concept development: During this stage, the findings from the study are examined for congruence and best fit in relationship to existing theories and application to disciplinary practice.

A major stumbling block to community-based work has been the lack of a well-articulated and comprehensive theory to guide the implementation of interventions and the evaluation of outcomes (Kubisch et al., 2002; Merzel & D’Afflitti, 2003). The emergent theory appeared to fill many of these theoretical gaps by providing an explanation that holds practical relevance for social change efforts. In particular, the emergent theory was able to clarify the position of often-used community concepts (empowerment, critical consciousness, and sense of community) and their relationship to the efficacy of collective action. In this way, the emergent theory did not replicate, displace, or discount these established concepts but provided a unifying framework with the potential for predictive validity. As a result of the research strategies, the emergent theory had reached a level of abstraction that showed potential to move across social contexts and cross-cultural settings. Situated in this manner, the emergent theory was now at a level of maturity, meaning the degree to which the concept is suitable for research purposes, where hypothesis testing was possible.

At the same time, the emergent theory was defined sufficiently to provide a basis for exploring measurement issues, the physiological association between social capital and health, and the macro-level social forces that create or destroy social capital within a social setting. The emergent theory also appeared to capture the anecdotal accounts of community practitioners and address the theory-practice gaps from that perspective (Bopp & Bopp, 2001; Campbell & MacPhail, 2002). In addition, the theory’s domains and attributes were conceptually congruent with international efforts to measure social capital (Grootaert & van Bastelaer, 2002). However, the theory went beyond these measurement efforts by suggesting a more parsimonious and unified framework for understanding how social capital is created and why it is weak or strong in certain communities. As a result, the emergent theory provides a framework for understanding why and how community-based participatory research efforts can be leveraged to increase community capacity for social change.

In summary, the purpose of this article was to provide a case study of moving through the methodological trajectory of problem identification, concept selection, concept refinement, and theory development suggested by the stages and strategies of the hybrid model (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 2000; Schwartz-Barcott, Patterson, et al., 2002). We used the case study approach both as an exemplar of the process of theory development and as an expression of the “craftsmanship” required in qualitative inquiry (Kvale, 1995). Although neither the hybrid model nor this case study is presented as an explicit instructional approach to theory development, both are presented as a guide to a sequential program of research that links the pragmatic demands of practice with relevant theoretical development. Throughout the trajectory is a theme of searching for the theoretical “best fit” with which to move forward to the next phase of research. In this way, problem identification in clinical practice is intimately intertwined with research and literature to produce theory with practical application and relevance for the clinical setting. The trajectory begins and ends situated in the context of disciplinary practice. Figure 7 provides a final visual representation of this methodological trajectory and the products of inquiry produced in each phase.

Figure 7. Overall methodological trajectory and the outcome produced at each stage and strategy

More important, because the purpose of this article was to focus on the methodological trajectory as process, this section provides an opportunity to discuss what constitutes the findings in this type of qualitative research. Sandelowski and Barroso (2002, 2003) have suggested that “finding the findings” in a qualitative report has proven to be extremely challenging. These authors discovered that too often, findings presented are actually raw data, the visual display of the data reduction strategies, or merely the identification of topics or themes without any interpretation of meaning. This misrepresentation can occur because qualitative researchers are at a loss as to how to present or what to present as their findings for a research report. Many are often unclear concerning the distinction between qualitative data, analysis categories, and research findings. However, we found that the stages and strategies of the hybrid model helped to define both the process and the products of the inquiry.

In the final stages, it was evident that the end product was not the quotes from the interviews, the visual schematic representations of the codebook, or even the findings particular to any one neighborhood. The end product of the inquiry was the theory of social capital that emerged as the study progressed. The data exemplars from each stage of the research project provided a representative description of the findings but, by themselves, were not the findings of the research study. Yet, each successive stage of the process produced important findings and a significant research product on its own. The stages and strategies of the hybrid model were the means to guide and clarify those findings.

In this article, I have presented a case study of a systematic research methodology that resulted in a refined theory of social capital. Although the sequential phases of the methodological trajectory were time consuming, entailing more than 3 years of research effort, the theory of social capital that emerged offers a significant contribution to health disparities research and community-based practice. The emergent theory suggests a new framework to explore racial and ethnic health disparities across a wide range of health outcomes and geographic settings. The theory also provides a framework that suggests appropriate intervention strategies. The purpose of this article was to demonstrate how the stages and strategies of the hybrid model of concept development were extended to form a systematic research trajectory that produced this emergent theory of social capital.

American Heritage Dictionaries (Ed.). (1997). American Heritage College Dictionary (3rd. ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Bachrach, C. A., & Abeles, R. P. (2004). Social science and health research: Growth at the National Institutes of Health. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 22-28.

Bopp, M., & Bopp, J. (2001). Recreating the world: A practical guide to building sustainable communities. Calgary, Canada: Four Worlds.

Brown, P. J. (1998). Understanding and applying medical anthropology. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Campbell, C., & MacPhail, C. (2002). Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 331-345.

Carlson, E. D., & Chamberlain, R. M. (2003). Social capital, health, and health disparities. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 35, 325-331.

Carlson, E. D., & Chamberlain, R. M. (2004). The Black-White perception gap and health disparities research. Public Health Nursing, 21, 372-379.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Drevdahl, D., Kneipp, S., Canales, M. K., & Dorcy, K. S. (2001). Reinvesting in social capital: A capital idea for public health nursing? Advances in Nursing Science, 24(2), 19-31.

Druskat, V. U., & Wolff, S. B. (2001). Group emotional intelligence and its influence on group effectiveness. In C. Cherniss & D. Goleman (Eds.), The emotionally intelligent workplace (pp. 132-155). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (Eds.). (1999). Social identity. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Emmons, K. M. (2000). Health behaviors in a social context. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social epidemiology (pp. 242-266). New York: Oxford University Press.

Forbes A., & Wainwright, S. P. (2001). On the methodological, theoretical and philosophical context of health inequalities research: A critique. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 801-816.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1970)

Goodman, R. M., Speers, M. A., McLeroy, K., Fawcett, S., Keglelr, M., Parker, E., et al. (1998). Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Education & Behavior, 25, 258-278.

Grootaert, C., & van Bastelaer, T. (2002). Understanding and measuring social capital: A multidisciplinary tool for practitioners. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hupcey, J. E., Penrod, J., Morse, J. M., & Mitcham, C. (2001). An exploration and advancement of the concept of trust. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36, 282-293.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. (2003). Introduction. In I. Kawachi & L. F. Berkman (Eds), Neighborhoods and health, (pp. 1-19). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., & Glass, R. (1999). Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1187-1193.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., Lochner, K., & Prothrow-Stith, D. (1997). Social capital, income inequality and mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1491-1498.

Krishna, A. (2002). Active social capital: Tracing the roots of development and democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Krishna, A., & Uphoff, N. (1999). Mapping and measuring social capital: A conceptual and empirical study of collective action for conserving and developing watersheds in Rajasthan, India (Social Capital Working Paper No. 13). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Kubisch, A. C., Auspos, P., Brown, P., Chaskin, R., Fulbright-Anderson, K., & Hamilton, R. (2002). Voices from the field II: Reflections on comprehensive community change. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute.

Kvale, S. (1995). The social construction of validity. Qualitative Inquiry, 1, 19-40.

Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. H. (1995). Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Lynch, J., Due, P., Muntaner, C., & Smith, G. D. (2000). Social capital—Is it a good investment strategy for public health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 54, 404-408.

Merzel, C., & D’ Afflitti, J. (2003). Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 557-574.

Morse, J. M. (2004). Constructing qualitatively derived theory: Concept construction and concept typologies. Qualitative Health Research, 14, 1387-1395.

Morse, J. M., Hupcey, J. E., Penrod, J., & Mitcham, C. (2002). Integrating concepts for the development of qualitatively-derived theory. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 16, 5-18.

Oakes, J. M. (2004). The (mis) estimation of neighborhood effects: Causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1929-1952.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ridley, M. (1996). The origins of virtue: Human instincts and the evolution of cooperation. New York: Penguin.

Saegert, S., Thompson, J. P., & Warren, M. R. (Eds.). (2001). Social capital and poor communities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2002). Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 34, 213-219.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 905-923.

Schwartz-Barcott, D., & Kim, H. S. (1986). A hybrid model for concept development. In P. L. Chinn (Ed.), Nursing research methodology: Issues and implementations (pp. 107-133). Rockville, MD: Aspen.

Schwartz-Barcott, D., & Kim, H. S. (2000). An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid model of concept development. In B. L. Rodgers & K. A. Knafl (Eds.). Concept development in nursing (2nd ed., pp. 129-159). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Schwartz-Barcott, D., Patterson, B. J., Lusardi, P., & Farmer, B. C. (2002). From practice to theory: Tightening the link via three fieldwork strategies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39, 281-289.

Simmons, A. (1999). A safe place for dangerous truths. New York: Amacom.

Simmons, A. (2001). The story factor: Inspiration, influence, and persuasion through the art of storytelling. Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., Nelson, A. R. (Eds.). (2002). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Smedley, B. D., & Syme, S. L. (Eds.). (2000). Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Strauss, C., & Quinn, N. (1997). A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Subramanian, S. V., Kim, D. J., & Kawachi, I. (2002). Social trust and self-rated health in U. S. communities: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 79(Suppl. 1), S21-S34.

Uphoff, N. (2000). Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. In P. Dasgupta & I. Serageldin (Eds.), Social capital: A multifaceted perspective (pp. 215-249). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Uphoff, N., Esman, M. J., & Krishna, A. (1998). Reasons for success: Learning from instructive experiences in rural development. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24, 369-387.

Ward, E., Jemal, A., Cokkinides, V., Singh, G. K., Cardinez, C. C., Ghafoor, A., et al. (2004). Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Cancer: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 54, 78-93.

Watts, R. J., Griffith, D. M., & Abdul-Adil, J. (1999). Sociopolitical development as an antidote for oppression. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 255-271.

| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (3) September 2005 |