June 18, 1999

A century of living with Treaty 8

School of Native Studies

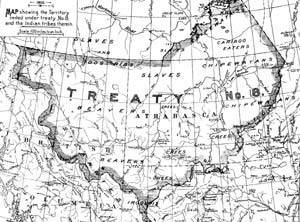

Map showing territory ceded under Treaty 8 |

The treaties have been enormously influential in structuring many aspects of aboriginal life, affecting even personal and community identities. Once aboriginal leaders had signed each treaty, legal "Indian bands" were constructed and their members were listed in the Indian Registry. They became "Indians" as defined by the Indian Act, whose provisions thereafter governed their affairs. Today, the meanings of the treaties are argued in court cases and involve not only the formal, written texts and commissioners' reports, but also the oral traditions told by elders.

Its history

Treaty 8 was negotiated in the summer of 1899 as the first northern treaty. Although a treaty had been proposed for several years, it was finally precipitated by the invasion of aboriginal territory by hopeful prospectors on overland routes to the Klondike gold fields. (Ironically, no treaty was ever negotiated in the Yukon itself, although Chief Jim Boss requested one in the Whitehorse area as early as 1903.)

The members of the Treaty Commission traveled the fur trade transport routes that had been re-shaped after Confederation by railway connections from eastern Canada to Fort Edmonton. They took overland trails to Athabasca Landing and Peace River Crossing. In short, the lands that were officially ceded under Treaty 8 were those comprising Edmonton's economic hinterland. They included vast amounts of Canadian real estate-those portions of the Northwest Territories that would later become northern Alberta, northeastern British Columbia, the southern Northwest Territories and northwestern Saskatchewan.

The treaty party began its work at Lesser Slave Lake Settlement (present-day Grouard), where the treaty was first signed on June 21, 1899. The signing was followed immediately by the work of the Half-breed Scrip Commission, which negotiated with Métis about the form Métis scrip should take, and then heard claims for Métis scrip (scrips were coupons which could be exchanged for land or cash).

Because these aboriginals lived in small, widely scattered bands, members of the two commissions visited several communities, ending the season's work at Smith Landing (now Fort Fitzgerald). In 1900, a second commission traveled as far north as Fort Resolution, taking adhesions to the treaty and hearing additional applications for scrip.

Its impact

Although Treaty 8 was similar to the other numbered treaties, as a northern treaty its negotiation and impacts were significantly different than in the south. For example, signatories to Treaties 6 and 7 knew their bison-based economy was ending, and they were eager to explore new sources of livelihood. In the north, the mixed economy based on land-based resources for both subsistence use and exchange, coupled with wage labor, was thriving. Northern peoples wanted assurances that signing the treaty would not interfere with their ability to support themselves.

In the south, status Indians quickly found themselves confined to reserves, with much of their economic activity administered for them by the local Indian agent. In the north, it was clear Aboriginal Peoples would not sign Treaty 8 unless they were reassured they would not have to live on reserves. And, with much of Treaty 8 situated within the boreal forest and unsuitable for agrarian activities, subsequent reserve life was often different from that in the south. Reserves were not established everywhere in the Treaty 8 region. Where they were created, their members continued to utilize the resources of the bush and did not commit to agriculture. As a result, Indian agents never enjoyed the kind of power over those members as they had in the south.

Neither treaty nor scrip brought the expected benefits to aboriginals. Thanks to the complexities involved in redeeming scrip, Métis were willing to sell their benefits to the scrip buyers who accompanied the commissions, purchasing scrip at a greatly depreciated rate. Many Métis realized only a short-term cash value.

The years that followed the signing of the treaty were characterized by expanding regulatory structures imposed by federal and provincial jurisdictions. These interfered with the ability of all Aboriginal Peoples to support themselves from land-based resources and encouraged competing land uses by non-aboriginals. Treaty Indians considered most of these measures to be direct violations of treaty promises, yet had little recourse until recent decades.

They would meet annually with the Indian Affairs representative to receive their annuities and discuss the year's occurrences and difficulties. These meetings typically occurred in the early summer at the major trading posts where the treaty had been signed. They were serious business and on several occasions the leaders refused to receive the annuities until their concerns were addressed. Today, the negotiations that once occurred in the communities take place in courtrooms and in provincial and federal capitals between band officials and senior government officials, while the community meetings have evolved into festive "treaty days," or contemporary community celebrations.

In this anniversary year, Treaty 8 communities are commemorating-though not celebrating-the 100th anniversary of this signal event. Treaty Days observances will simultaneously evoke the long history of the past and attest to the persistence of the government-to-government alliance established by the treaty. To the re-vitalized First Nations communities of the Treaty 8 region, the treaty is a key charter document, and they insist on the fulfillment of its terms by the federal government.