January 24, 2003 |

Good fish, bad fish? | |

|

by

Richard Cairney

Folio Staff

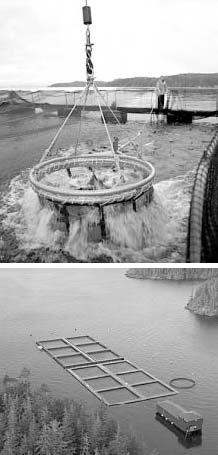

Fish is a part of any healthy diet, right? Not necessarily, says University of Alberta fisheries ecologist Dr. John Volpe, who believes the farmed salmon found on supermarket shelves represent a major environmental threat and probably aren't good for you. It isn't widely known on the Prairies, but almost all of the fresh salmon sold at supermarkets and served at restaurants is grown in one of approximately 100 ocean-based salmon farms that dot the waters off the British Columbia West Coast. The salmon, Volpe says, have high concentrations of toxins because of their diet - the salmon farming industry feeds their stocks a high-fat diet, he says. The fat in that diet comes from fish like mackerel and anchovies harvested from southern oceans. When the catch is processed, its fatty content is separated and forms a major ingredient in the food fed to farmed salmon - along with antibiotics and a synthesized chemical, which gives the fish a healthy-looking, pink glow. The trouble with that diet, says Volpe, is that fat is where toxins, like dioxins and PCBs, are stored. By feeding their captive fish high-fat diets, farmers are also multiplying the amount of toxins they'd ingest in the wild. At the same time, he observes, South American fisheries are being depleted in order to feed farmed fish, which are grown to compensate for the collapse of North American fisheries. It gets worse. According to Volpe, a salmon absorbs only 15 to 17 per cent of the nutrients it eats - the rest of it is excreted and falls to the ocean floor along with food that isn't even consumed in the first place. The fish are hemmed in nets and farmed in close, crowded conditions; Atlantic salmon are farmed because they survive such conditions better than Pacific salmon do. But farm fish escape when animals or boats rip holes in the enclosures. Last year, Volpe published a report that showed escaped Atlantic salmon are surviving and spawning in Pacific salmon territory, and he fears the more aggressive breed may muscle the docile B.C. fish out of its own territory. If that doesn't happen, Volpe fears, disease spread from the fish farms will further decimate Pacific salmon, which are already vanishing at an alarming rate. At the Broughton Archipelligo on the West Coast last year, fishers were expecting four million Chinook salmon to return to freshwater rivers to spawn - an estimated 50,000 showed up. "We are witnessing the complete collapse of Pacific salmon populations," Volpe said, adding that disease from the farmed fish may just finish the job. Sea lice are a common parasite that prey on salmon. But when there is an outbreak of sea lice at a salmon farm, antibiotics used to battle the infestation don't affect the sea lice that float beyond the enclosure. "You've got these farms producing, literally, clouds of sea lice in the water, and these farms are located in the belly of bays - where salmon rivers flow into the ocean," said Volpe. "The smaller salmon that leave those rivers are going to have to swim through those clouds of sea lice - and two lice will kill them." Farmed fish, Volpe says, are unhealthy - and he characterizes the fish farming industry as an ecological menace. But government and the industry itself dispute findings by scientists like Volpe and claims made by groups like The David Suzuki Foundation and The Friends of Clayquot Sound, which are highly critical of fish farms, comparing them to ocean-bound feedlots. For years, aboriginal groups and environmentalists have been at odds with fish farmers. Last summer, anti-fish farm protesters dumped a rotting salmon at the B.C. legislature. Native groups have long demanded that the province stop expansion of the industry. But the B.C. government has just lifted a seven-year moratorium on the number of allowed fish farms in response to concerns about the impact the operations have on the environment. For consumers, though, the first question is one of safety - is it OK to eat farmed salmon? Klaus Schallie, an aquaculture and shellfish specialist with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in Vancouver, says it is. "This is one of these issues where the science is beyond the ken of a large percentage of the public, so you've got a lot of conflicting information," Schallie said. The fish farming industry conducts its own tests for toxins and levels of antibiotics and the agency follows up on that self-regulation with "statistically significant spot checks," Schallie said. "We test farmed salmon and wild salmon - we test pretty well every kind of seafood on the market in Canada - for chemicals of concern. And farmed salmon is a perfectly safe food," he said. "There are no harmful levels of contaminants." But even if the product is healthy, environmental concerns abound. Environmentally responsible consumers may not want to purchase a product if it pollutes the oceans and exploits southern fish stocks as a food source to prop up an industry that is growing only because we've overfished our own fish stocks. Brad Hicks has been involved in salmon fish farming as an owner and employee since the early 1970s. A veterinarian and board member of the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association, Hicks says criticisms of the industry are unfounded. In terms of environmental impact, he says estimates of fish farming's dismal return on investment in terms of energy use and recovery are inaccurate. Fish farming is more efficient than harvesting wild salmon, he says, because a higher percentage of farmed fish - about 97 per cent -makes it to market. Only 60 or 70 per cent of wild salmon make it to market because of bruising and spoilage. The use of fish like anchovies and mackerel harvested from southern oceans and used to produce food for the fish farms represents a transfer of those southern fish stocks and not an increase in those harvests, he noted. Once, poultry and pork producers used those southern fish stocks as animal feed and now fish farmers use it. "It's a reallocation of fishmeal to fish farmers, and it has come from primarily poultry and pig farmers because we can afford to pay for it and they can't," he said. Excrement from pens containing hundreds of thousands of fish in crowded conditions can have a tremendous environmental impact, causing plankton blooms and possibly destroying shellfish beds. But Hicks says provincial government regulations ensure fish farms don't foul their surrounding environment. Regulators ensure the environment surrounding a farm site is capable of naturally absorbing the amount of excrement the farmed fish will produce. And on the topic of farmed fish escaping, he says farms are neither to blame nor are they the biggest culprits. Governments of Alaska, B.C., Russia, and the U.S. have been breeding and releasing salmon stock for years. "When you get into arguments about genetic pollution and blah, blah, blah, you can't pick on farmers . . . that has occurred for a long time and has absolutely nothing to do with fish farmers," he said. "The horse has already escaped from the barn if that is even an issue." Volpe insists it is. "Hatcheries produce fish for the purpose of supplementing sport fishing because a fish is a fish is a fish, (but) that has been demonstrated to be categorically wrong," he said. Salmon populations return generation after generation to the same spawning grounds and after thousands of years "tailor themselves" to the specific characteristics of that river system. Fish stock A from one river will be different than fish stock B from another river, he says. "If you then say 'a salmon is a salmon is a salmon' and rear stock C in a hatchery ... and allow C to breed with A and B, we now have a coast-wide homogenous single mongrel stock with none of the requisite characteristics that allowed stock A to exploit the resources in its environment." In fact, Volpe suspects a Department of Fisheries doesn't get accurate reports from B.C. fishers about the number of escaped Atlantic salmon they catch. He has just created a 1-800 line, asking those fishers to report escaped salmon they've captured. Given the conflicting views, it's difficult to know whether farmed fish are good or bad. Hicks has a financial interest in the industry - why should he be believed? "The overlying issue here is whether or not we are going to privatize the last commons," he said. "That is what is really underlying the debate. The reason you see all this other stuff that doesn't make a whole lot of sense . . . why are they describing us as a threat rather than as we are? Because they can regulate us, which gives them power when it comes to developing public policy. The issues aren't environmental issues per se." And for his part, Volpe asks only that people consider scientific evidence. "I would ask, 'Where is the data?' The difference is that there is a mounting pile of peer reviewed independent research all pointing in the same direction. It's countered from the industry and government with a lot of misdirection and smoke and mirrors. 'Don't worry, be happy.' I say let the weight of the evidence speak for itself."

FURTHER READING

| ||