September 7, 2007 | |

King me: Schaeffer solves checkers, then challenges poker champsConcrete achievements in artificial intelligence research | |

by Richard Cairney

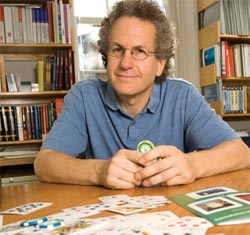

Jonathan Schaeffer returned from a vacation in late August and began preparing to teach a fourth-year computing science class. Typical. But Schaeffer's summer was anything but ordinary. "I've had media attention before, but this summer was ridiculous. It went on for a whole week, from nine to five, skipping lunches and even doing interviews in the evening," he said. "I don't know how celebrities handle it. I now have some sympathy for the Brad Pitts of the world." Schaeffer was involved in two high-profile research projects which broke within a week of each other in July. The first was the culmination of an 18-year research project in which Schaeffer solved the game of checkers. After sifting through 500,000,000,000,000,000,000 (500 billion billion) checkers positions, Schaeffer and his colleagues built a checkers-playing computer program that cannot be beaten. Completed in late April, the Chinook program may be played to a draw but will never be defeated. Results of the research appeared in the July edition of the academic journal Science. "I think we've raised the bar - and raised it quite a bit - in terms of what can be achieved in computer technology and artificial intelligence," said Schaeffer, chair of the U of A Department of Computing Science. Checkers is the largest non-trivial game of skill to be solved - it is more than one million times bigger than Connect Four and Awari, the previously biggest games that have been solved, Schaeffer added. Solving checkers "is more than a million times bigger than what had been solved before - a million times. When you look at scientific research most of it is in incremental advances. Someone will improve an algorithm by 10 per cent. That is the norm," said Schaeffer. "I foolishly committed myself to doing something that, circa 2007, was more than a million times bigger than anything anyone had done before. And when I started in 1989, it was a trillion times bigger. Now I look back on it and say I was just naieve. No one in their right mind would have done this because it was just too big of a problem." Schaeffer created Chinook to exploit the superior processing and memory capabilities of computers and determine the best way to incorporate artificial intelligence principles in order to play checkers. With the help of some top-level players, Schaeffer programmed heuristics ("rules of thumb") into software that captured knowledge of successful and unsuccessful checkers moves. Then he and his team let the program run, while they painstakingly monitored, tweaked and updated it as it went. An average of 50 computers - with more than 200 running at peak times - were used every day to compute the knowledge necessary to complete Chinook. Now that it is complete, the program no longer needs heuristics - it has become a database of information that "knows" the best move to play in every situation of a game. If Chinook's opponent also plays perfectly the game would end in a draw. "We've taken the knowledge used in artificial intelligence applications to the extreme by replacing human-understandable heuristics with perfect knowledge," Schaffer said. "It's an exciting demonstration of the possibilities that software and hardware are now capable of achieving." Schaeffer started the Chinook project in 1989, with the initial goal of winning the human world checkers championship. In 1990 it earned the right to play for the championship. The program went on to lose in the championship match in 1992, but won it in 1994, becoming the first computer program to win a human world championship in any game -a feat recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records. Chinook remained undefeated until the program was retired in 1997. With his sights set on developing it into the perfect checkers program, Schaeffer restarted the project in 2001. "I'm thrilled with this achievement," he said. "Solving checkers has been something of an obsession of mine for nearly two decades, and it's really satisfying to see it through to its conclusion." "I'm also really proud of the artificial intelligence program that we've built at the University of Alberta," he added. "We've built up the premier games group in the world, definitely second-to-none. And we've built up a strong, international, truly world-class reputation, and I'm very proud of that." Schaeffer's second big project was to pit his research team's computer poker program Polaris, against two of the world's top poker players, Phil 'the unabomber' Laak and Ali Eslami. The match up took place over two days at the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence's annual conference in Vancouver, B.C. Schaeffer, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Artificial Intelligence, said the event was a natural evolution of the 1994 match between IBM's Deep Blue chess program and then-world chess champion Gary Kasparov. "The difference is that chess is a game of perfect knowledge, meaning there is nothing hidden from the players. In poker you can't see your opponent's hand, and you don't know what cards will be dealt. This makes poker a much harder challenge for computer scientists from an artificial intelligence perspective," Schaeffer said. The competition featured four Texas Hold 'Em matches between Polaris and the two poker professionals. The tournament was designed to eliminate luck and focus on skill. In each match, Laak and Eslami played simultaneously against Polaris in separate rooms. At the end of each match, Laak and Eslami combined their chip totals and compared them against Polaris' combined total. In the end, Laak and Eslami won three of the four matches. "The final result was kind of arbitrary in that the only reason they won more than us was that was the match boundary, that after 500 hands we would stop playing," said Schaeffer. "Our programs played extremely well we are thrilled with the result and it only whetted our appetite to do it again." "I think the humans had better be wary." In poker, anyways. Schaeffer cites a lengthy list of applications in which artificial intelligence helps in our day to day lives, from scheduling airline flights so that goods and pilots are moved around in the most efficient ways possible, to programs that monitor your our habits in order to detect credit card fraud. Even now, as he was preparing for fall classes, Schaeffer was still doing interviews about the checkers breakthrough, although requests have slowed to a trickle. And he's happy to be getting back into a regular routine. "It is nice to being back to being a mere mortal." |