COMMENTARY: Anti-BIack racism and difficult conversations

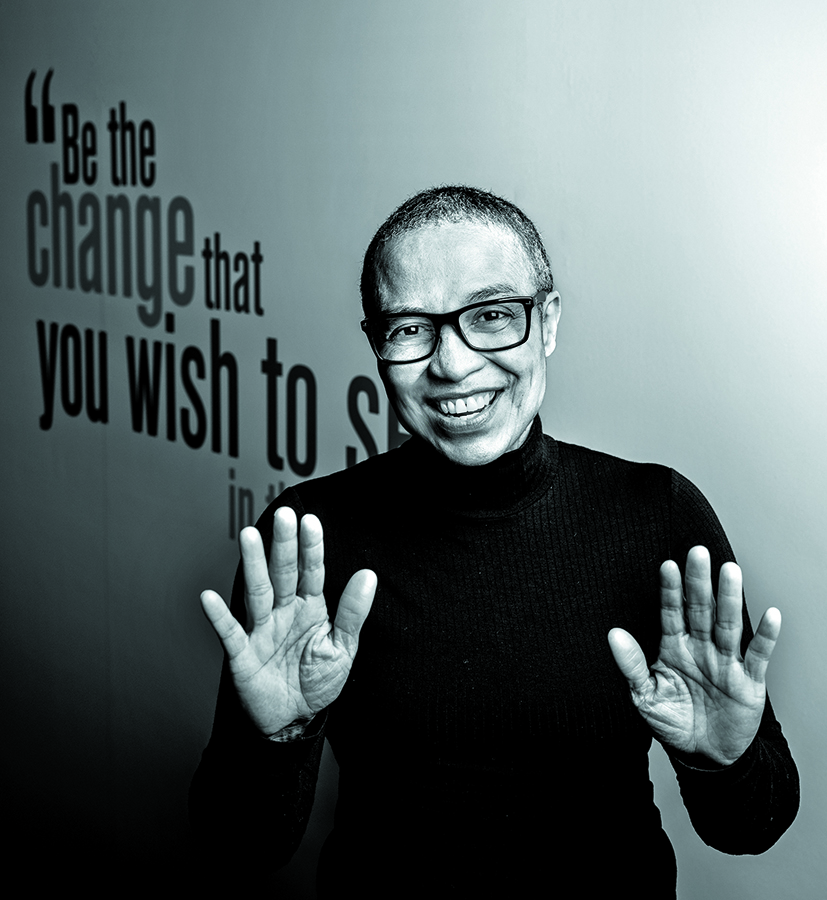

Shirley Anne Tate - 24 February 2021

Fifty-two years ago, there was a student-led anti-racist protest at Sir George Williams University (now part of Concordia University) in Montreal. Protest began after complaints by Black Caribbean students to the university administration that they experienced unfair marking practices and racial discrimination from Professor Perry Anderson of the biology department.

Perry said that as ‘affirmative action’ students, Black Caribbean students could not grasp course material. He gave them lower grades for work that was comparable to that of white students who got higher grades. The students asked the university to set up a committee to look into their complaint in 1968. The complaint was dismissed on January 29, 1969.

The complainants and about 200 other students peacefully occupied the Computer Centre in Henry F. Hall Building in protest. February 10, 1969 negotiations failed and students barricaded themselves inside the building. The police arrived on February 11 and 97 students, Black and white, were arrested.

Perry was reinstated the next day and the complaint of racism against him dropped. Roosevelt ‘Rosie’ Douglas, a McGill student who was identified as the ringleader, served two years in prison and was deported back to Dominica in 1975. Anne Cools from Barbados, sentenced to four months in prison, was pardoned. She moved to Toronto in 1974, founded Women in Transition Inc for abused women, and later became the first Black person appointed as a Canadian senator.

Changes were made to student representation in decision-making, a new set of regulations/rights were adopted by the university, an Ombudsman’s office to hear student concerns was set up, and there was a wider discussion on racism in Canada. In 2000, when Roosevelt Douglas came back to Canada, he said that the uprising was about Black people having equality and they had just wanted justice.

Racial justice was taken-up by universities in 2020/21, not because of Black Canadian history but George Floyd’s death and global Black Lives Matter protests. This spoke in an unprecedented way to continuing systemic institutionalized anti-IBPOC (Indigenous, Black and People of Color) racism’s violence and death on Turtle Island. Universities’ calls to action for racial social justice took the form of solidarity statements following BLM 2020 like that from U of A past President and Vice Chancellor, David Turpin, which I will summarize below. Read the full statement here.

The need to build an anti-racist university as a space in which IBPOC students, faculty and staff can thrive is urgent. In BHM, I would like to dwell on a few aspects of the call to action that I have italicized below because of the difficult conversations they ask us to have institutionally and individually and how they resonated with me by speaking about the systemic lack of progress on racial social justice.

The UoA is committed to uplifting the whole people. We condemn anti-Black racism and stand with Black communities in demanding justice and progress on equity for racialized members of our society. It has been 52 years since the SGWU uprising and there is still a need for this demand for social justice even after decades of EDI work in universities. The demand for social justice is still necessary because of continuing white settler coloniality. As Black people, we still experience ‘thingification’[1] as ‘bodies out of place’[2], as not HuMan[3], therefore, we are placed outside ‘the whole people’ being uplifted.

Drawing on Fanon, Wynter, and Tuck and Wang’s[4] insistence that ‘decolonization is a not a metaphor’ means that we have to remember the entanglement of decolonial and anti-racist social justice transformation initiatives. They cannot be separate because in Turtle Island and elsewhere decolonization and antiracism are integral to each other. Nor can we have a position that says that different forms of racism have precedence over others. All forms of racism cause harm.

Equity remains difficult because of the rise in university audit cultures with no clear resulting changes, the anti-IBPOC racist institutional culture that enables injustice to remain unchallenged and thrive, and the knowledge reparations that are still unfulfilled. Although we need good race based data for policy and practice development, we should not let audit cultures get in the way of thinking about how race, race-thinking and anti-IBPOC racism are maintained in our knowledge systems, institutional processes/practices/cultures/interactions.

For example, the prevalent idea that theory generated by IBPOC scholars is not-theory because it is too particularistic, incapable of being universal like white scholars’ work. We have to decide what the contours of antiracist decolonial education in terms of curriculum, pedagogy and teaching/learning environment should look like to produce racial social justice transformation and knowledge reparations.

To ‘stand with Black communities’, members of the community racialized as white must end their complicity in white supremacy, refuse ‘white fragility’[5], and recognize/ act against white privilege. There is no room for sitting on the fence, or for saying ‘that is a history long past which I had nothing to do with’. We take sides in social justice transformation. No one can sit it out and just wait to see what happens.

The acknowledgement of the pain, grief, anger and fear of our students, faculty, and staff is important. Anti-IBPOC racism has affective consequences. The affective life of racism in universities has meant that antiracist decolonial efforts stall as BIack students, faculty and staff continue to experience a cold climate with experiences ranging from micro-aggressions to outright violence. I want to say here that micro-aggressions are outright violence too, without diminishing IBPOC death and physical harm. Pain, grief, anger and fear impact, how we learn and work, how we intimately feel we belong, and how we can attach to institutions, colleagues and peers. The pain, grief, anger and fear experienced on a daily basis will produce distancing as we enable ourselves to have livable lives as students, staff and faculty. I will illustrate this through looking briefly at the distancing pain of anti-BIack racism[6].

Speaking of torture, Elaine Scarry (1985:52)[7] writes about the distancing of pain as essentially being about, ‘aversiveness’, ‘a pure physical experience of negation’, ‘something being against one and of something one must be against’. To me this describes the impact of the institutional pain of anti-BIack racism originating from white settler colonial supremacy. Starting from an analytics of anti-BIack racism is how I get through the grief, anger and fear on a daily basis. We need to move past acknowledgement of pain, grief, anger and fear to anti-racist action at the UoA.

It is necessary to support important research on intersectionality to understand and remove barriers. True. Yet, we are now in the midst of the Intersectionality and Critical Race Theory culture wars in the US and UK. What interests me here is how theory that speaks to Black experience/politics, white supremacy and anti-Black racism became a target in BLM 2020/21 protests and the continuing Covid pandemic crisis where IBPOC communities have been disproportionately affected. CRT and Intersectionality are key aspects of Black anti-racist and Black feminist thought that have revolutionized how we see race and racism operating societally and institutionally. They have given us analytics of white supremacy and racial subjection and a door to the possibility of Black liberation. They are academic interventions linked to political struggle that have made a difference. Attacks on CRT and Intersectionality are craven attempts to shut down debate on systemic racial inequality, institutional racism and continuing white supremacist privilege. This is a reminder to us of the urgency of the work needed to eliminate systemic and societal racism.

As we see from the 52 years between us, and the SGWU student protests, everything will remain familiarly the racist same without concerted anti-racist action. We must begin those difficult conversations.

[1] Frantz Fanon (1986) Black Skins, Black Masks

[2] Nirmal Puwar (2004) Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place; Shirley Anne Tate (2013) Racial affective economies, disalienation and “race” made ordinary

[3] Sylvia Wynter (2003) Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/ truth/freedom

[4] Eve Tuck and K.W Yang (2012) Decolonization is not a metaphor.

[5] Robin DiAngelo (2019) White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Race

[6] Shirley Anne Tate (2020) On brick walls and other Black decolonial feminist dilemmas: Anger and rcail diversity in universities

[7] Elaine Scarry (1985) The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World; Shirley Anne Tate and Azrini Wahidin (2013) Extraneare: Pain, loneliness and the incarcerated female body