I am largely indifferent to the Nobel organization, especially with respect to its literary awards. As many critics have observed, these awards are problematic. Typically, the Nobel award for literature generates controversy by either going to an utterly unknown author or poet, or by going to a well-known author or poet: whatever the case, some sort of debate on the issue of artistic merit versus popularity usually follows.

I am largely indifferent to the Nobel organization, especially with respect to its literary awards. As many critics have observed, these awards are problematic. Typically, the Nobel award for literature generates controversy by either going to an utterly unknown author or poet, or by going to a well-known author or poet: whatever the case, some sort of debate on the issue of artistic merit versus popularity usually follows.

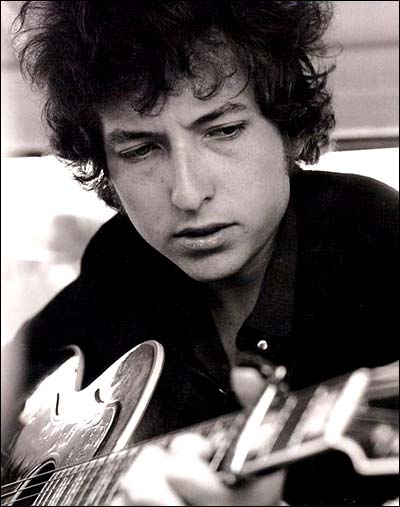

The case of Bob Dylan, our newest Nobel laureate, is slightly different. As Ryu Spaeth has recently observed in the New Republic, awarding Dylan the Nobel prize for literature is a "category error": that is, Dylan is a musician and songwriter, not an author or poet. Of course, there are many who would reject this argument, and insist vociferously that Dylan is a poet, that his lyrics are poetic, and that they can and should be read as poetry.

The pop music scholar Dai Griffiths has already made what I consider to be a very convincing case about song lyrics, identifying in them what he calls a "lyric" or "anti-lyric" impulse: song lyrics can be more "like poetry" or they can be more "like prose," but in the end are neither. Song lyrics should be heard and interpreted, in Griffiths' view, in terms of the relationship between "verbal space" and "musical space": in songs, words joined together to form lyrics occupy the space between the structural pillars set in place by harmonic rhythm, beat, phrase structure and other sonic parameters. Poetry does not share this landscape.

Poetry is rhythmic, even musical, but it does not do what song lyrics do, namely work synergistically with the primary elements of music: melody, harmony, rhythm and form. Critics of the decision to award Dylan the Nobel Prize have suggested that it is, in a sense, unfair to equate song lyrics and poetry, since a musician-songwriter enjoys the ability to join his words to music: in song, words are given extra expressive force and extra emotional depth in combination with musical sound. From this perspective, Dylan's Nobel Prize is less a revolution, less a triumph of the popular over the highbrow or an opening up of the field of literature, and more the outcome of an un-level playing field.

None of this is necessarily to disparage Bob Dylan as a song writer, popular icon, or important figure in the history of popular music. It is just to say that song lyrics are not poetry, nor should they be. Consider Leonard Cohen, perhaps the only other similar writer-performer in Dylan's league. Cohen is a poet. His poetry and his song lyrics are not the same. They do different things; they live in different worlds. Cohen's poetry is often powerful, moving, sublime; his songs, in my view, seem to uncomfortably straddle the fence of song and spoken word poetry and don't really work as songs. To my ears, they are musically shallow and overproduced, creating a stark disconnect and sense of alienation between singer, words, and music.

In contrast, Dylan's songs most certainly work as songs, rooted as they are in the American folk and pop music traditions, but I have spent the last few days seeking poetic profundity in Dylan's lyrics, to no avail. I find them trite, naïve, sometime pretentious and often boring. I don't mind listening to the songs as such-though, to be honest, I have never been a fan and have never fully understood the veneration of Dylan-but I would never make the mistake of thinking I was listening to poetry with musical accompaniment, or to an art song-like imbrication of deep poetic meaning and musical gesture.

It troubles me a little to think of Bob Dylan at the same table as other Nobel Laureates in the field of literature: picture Dylan in the company of T. S. Eliot, William Butler Yeats, or Alexander Solzhenitzen, if you can. On the one hand, I see Dylan receiving the Nobel Prize for literature as a symptom of a floundering and decadent culture: a culture with increasingly fluid standards, divorced from tradition, unmoored from its foundations. On the other hand, I console myself with the knowledge that Dylan was likely simply a nostalgic or legacy choice for the Nobel Committee-and perhaps part of its cynical attempt at appearing relevant by courting controversy.

In the end, literary prizes are usually viewed with considerable skepticism. After all, in its absurdly checkered history, the Nobel Committee rejected Tolstoy, Proust, Joyce, and Nabakov, to name a few. The addition of Bob Dylan as a Nobel Laureate, in light of such silliness, perhaps makes sense.

Alexander Carpenter, Music, Augustana Campus, University of Alberta. This column originally appeared in the Camrose Booster on November 22nd, 2016.