Sergio Serrano, Visual Artist (BDes '09) came to Edmonton in 2003 to begin his studies at UAlberta.

Sergio Serrano, the 33-year-old Edmonton visual artist who has already become a talent people know, if not by name, with works on display in several public spaces, recently took his friend to see Roma, the first Netflix film to spill over into Hollywood's turf with its Academy Award nomination for best picture. The film, by Mexican writer and director Alfonso Cuaron, is set in 1970s Mexico and is effectively a semi-autobiographical exploration of Cuaron's own nostalgia and memory.

Afterward, as he and his friend discussed the movie, Serrano says he translated the many small details that required a lived memory to understand. "I was telling him all of the things he missed just because he's not from Mexico. Like, there's the scene where there's this guy on a bike, playing a whistle. That guy sharpens knives and I know that because I know the sound of that whistle. My grandma would hear it and be like, 'Oh the knife sharpener is here, get all the knives.'"

The conversation was a natural one for Serrano to have. As someone working in a second language and an adopted culture, his work focuses on ideas of translation and communication. What allows us to communicate or prevents us? What meanings do we assign to otherwise meaningless objects, like, say, a whistle, that are actually about us rather than the objects? You can see this thinking working away in Serrano's 'zines, graphic design and holograms, and, shortly, even his 13 sculpted objects, which he's making with frequent collaborator Alexander Stewart and hanging from the ceiling of the Capilano branch of the Edmonton Public Library. All communicate something, often broken or warbled, about communication and meaning itself.

But let's back up. In 2003, Serrano left Coahuila, in northern Mexico, and arrived in Edmonton. He was 17. His dad had suggested he come to Edmonton because, Serrano says, as geologist he had contacts in Alberta in the oil business. "I think he was hoping I would follow his footsteps." That didn't happen. Instead, after taking a year of English courses, Serrano pursued his passion for art and enrolled in the bachelor of design program at the University of Alberta. And he excelled.

One of the people he first encountered was Sean Caulfield. "I saw right away how talented he was," Caulfield, a Centennial Professor, Fine Arts, at UAlberta, says. He first met Serrano in one of his printmaking classes, in 2011. Ever since then, every year, the two have collaborated on a project. "It's been a great ongoing collaboration. He's been a great energy for the whole Edmonton artistic community. He collaborates with all sorts of people, he's come from another culture and that meeting of perspectives is why he's had such a positive impact."

Serrano graduated from UAlberta in 2009 and immediately started making waves. First he made a name for himself as a graphic designer for hire with impressive flair. Next as an artist. By 2015, his personal work was featured in the Alberta Biennial, and then he collaborated with Stewart at Latitude 53. As they described it, the project was like "a game of broken telephone," where one would create an object to communicate something, and the other would respond with their own object. Though it examined communications barriers in a fog of information it was also somehow cheeky and fun, a Serrano quality.

"I feel a common thing [in my work] is - it's related to what I do as a designer as well - which is to do with communication," Serrano says. "In my design job, what I do is I try to communicate something as efficiently as possible, whereas the things I do that are more personal projects, I like to explore ways in which sometimes that's not always the case or possible, and instances where that communication breaks down because of differences in experience or language."

This focus is subtly influenced by Serrano's own experience. To this day, he says the biggest challenge for him is working in another language and with another set of cultural signifiers. Nevertheless, his decision to stay rather than return after school, or attempt to spread his wings in an even larger city, has been a relatively easy one. He says he quickly found a community here and says the city supports those who work in different artistic practices. And he says the U of A's intricate connection to many these communities also helps.

Soon, Serrano will stay in Edmonton in a more material sense, too, by adding more public art to his (and Stewart's) 2015 'Brother Mountain' lenticular mural, at Castle Downs Park. This one will be at Capilano Library and is focused on meaning and communication.

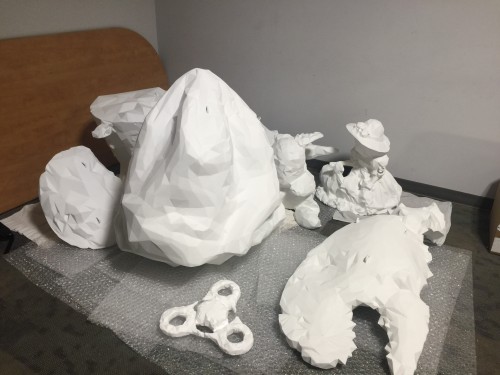

Serrano is proud of the long thinking and execution that have gone into it all. Over the past two years, Serrano and Stewart have held workshops with local residents, who bring in objects for the artists to 3D scan, and then tell them what these objects mean to them. Serrano's favourite is of a dog. "At one event, we had this lady talk to us and she was like, 'I'll go home and bring something.' She went home and asked her kids what they wanted to submit and she came back with a dog. So we were trying to 3D scan this dog. The face is all blurry. But then she was saying how the dog was sick and that it was going to pass soon, and everyone was really emotional."

The dog was one of the almost 200 objects Serrano and Stewart scanned during the community engagement process, of which 13 objects turned into sculptures made out of foam. "This is kind of part what the project is about," Serrano says, talking of an eventual sculpture of a dog that the viewer will not fully understand when looking at it. "Finding objects and not knowing the history somebody has assigned to that object, and not being able to access the emotional value that object may have for people individually."