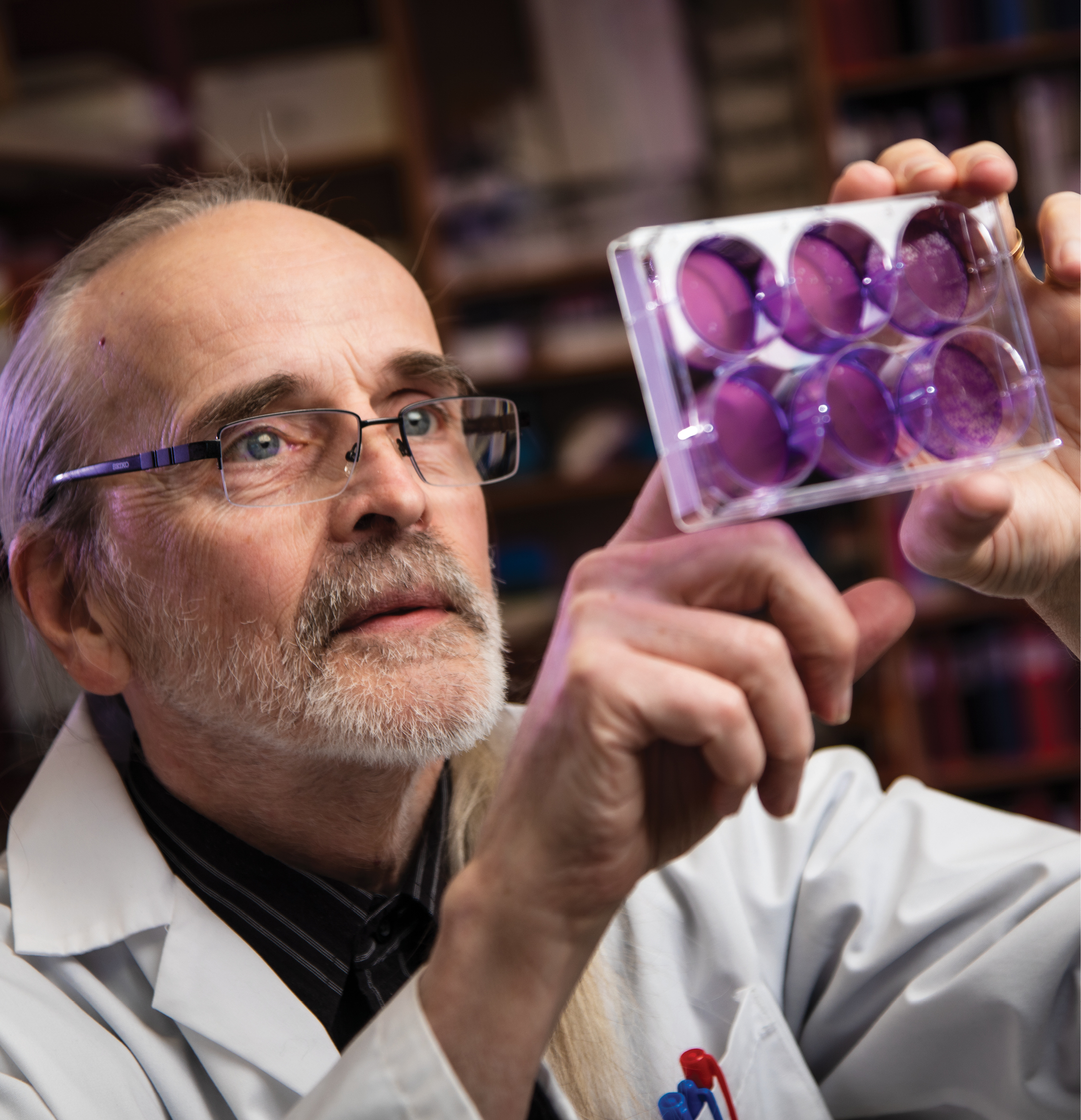

Sixty-six-year-old Powel Crosley obtained a master's degree in oncology last fall, inspired by his late wife's battle with ovarian cancer.

Photo: Laughing Dog Photography

When his wife died of a rare ovarian cancer 10 years ago, Powel Crosley, '19 MSc, vowed to find a cure.

Despite a lack of scientific training at the time, he is now within sight of a potential clinical trial for a treatment.

The 66-year-old graduated in November with a master's degree in oncology from the University of Alberta. In the near future, his work could be the basis for a clinical trial of a new treatment for granulosa cell tumour (GCT).

"When you sit down and start looking back at everything, so much is just serendipity," Crosley says. "It just happened. Crazy."

Learning inspired by loss

Sladjana Crosley died in 2009 after a 13-year battle with a dire prognosis.

Of the 225 Canadian women diagnosed with GCT this year, roughly one in three will see the cancer return. Barring advances, four out of five of those women will die.

Throughout her recurring illness, Sladjana refused to accept the odds. A chemical engineer by training, in 2004 she founded the Granulosa Cell Tumour Research Foundation (GCTRF) and gathered an online community of women facing a similarly grim future.

Without major funds or established connections to research laboratories, progress remained elusive. For Sladjana, the surgeries became more aggressive, more frequent and less effective. The cancer continued down its inevitable path while scar tissue eventually made it too risky to go under the knife again.

After Sladjana died, Powel vowed to continue leading the foundation she started. He started running marathons to raise money for research and enrolled at the U of A, taking chemistry, biology and genetics courses to better understand the disease.

Turning point

Under Crosley's leadership, the GCTRF has raised more than $300,000 for research, a series of small grants dispersed in labs around the world. And after an upper-level oncology class with Mary Hitt, PhD, Crosley began conducting experiments in her lab and soon became a permanent fixture there, working long hours seven days a week.

Hitt says having him in the lab has meant young researchers get a chance to work with a role model who treats science as more than just theory.

"To have him in the lab right there, it's in your face, 'There are people dying of cancer and we have to do something about it,'" says Hitt, who is a member of the Cancer Research Institute of Northern Alberta. "It's not just playing around with cool toys in the lab."

Crosley eventually moved on to testing PAC-1-a drug Sladjana had spotted years earlier in an academic journal-and eventually decided to carry on into a master's degree.

Building toward a cure

Crosley's project has also added TRAIL, a natural protein that was hailed in the 1990s for its promising ability to cause 'suicide' in cancer cells, but has since proven unstable and prone to resistance.

The early lab results combining PAC-1 and TRAIL have shown they could work well together. Through the foundation, Crosley has been in touch with Paul Hergenrother, the University of Illinois chemist who created PAC-1 and is conducting a clinical trial of the drug. Crosley believes the trial could be expanded to include TRAIL, which would be a dramatic step toward a potential treatment for GCT.

Crosley has also worked with Hitt to modify a virus that could potentially "trick" GCT cells to produce TRAIL on their own, which could help move toward a more targeted treatment.

For the next two years, he'll remain a researcher in Hitt's lab. Thanks to a research proposal drafted largely by Crosley, Hitt has received a $120,000 grant to try out the combination therapy in animal trials.

The grant, awarded by the Cancer Research Society, matched a $60,000 fundraising campaign spearheaded by the GCTRF, the organization Sladjana founded. It's just another touch of serendipity, Crosley says, a reminder of his wife's tireless efforts to help thousands of women find a better prognosis.

"I feel a sense of responsibility. I see how much hope these women have invested in this," says Crosley. "I think Sladjana would be pretty excited by the science."