Douglas Zochodne

Leading up to World Diabetes Day on November 14, the University of Alberta recognizes the importance of raising awareness about the effects of diabetes on our communities, and the efforts of health professionals to improve patients' lives and find a definitive cure.

Approximately one half of diabetic patients develop polyneuropathy, peripheral nerve damage that can, in some patients, cause pain described as 10 out of 10, 24/7.

"There is numbness in the hands and feet," says Douglas Zochodne, divisional director of neurology at the University of Alberta's Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry and scholar with the Alberta Diabetes Institute. "People notice a lack of dexterity using their hands, loss of balance because they can't tell what their feet are doing." And then there is pain, in some, severe.

The biggest risk of polyneuropathy is that it predisposes people to foot ulcerations and then amputation, says Zochodne. In fact, diabetes is the most common contributing factor to the need for amputation. And while tight control of glucose levels may lower other risks, it has a limited impact on preventing polyneuropathy or its progression.

The impact on patients is profound. Their quality of life diminishes. Their ability to earn a living or to take care of themselves may decline. They may develop depression. One of Zochodne's patients committed suicide when his career in the sport he loved was lost.

"We have a number of people in the clinic who say their lives are wrecked," says Zochodne. "They want you to cut off their hands and feet because of the pain."

He remembers, with frustration, one such case of a man in his 20's who was requesting arm amputation because of severe nerve damage (in his case not due to diabetes). "I thought, the arm is intact, the muscles are there, the skin, everything. If we could just get the nerves to grow back, to allow his arm to work and to help the pain settle so as to give him some function."

That is exactly what Zochodne and his research team is working on by looking at two targets: insulin as a fuel to promote nerve growth, and PTEN, a growth inhibitor that acts like a brake system.

"Insulin is a potent growth factor for nerves," says Zochodne. "We're wondering if part of the problem might be lack of insulin signaling on these nerve cells causing them to degenerate." Nerve cells in a dish or in animals increase growth when you add insulin directly, he says.

Why this research matters

To patients:

More than 100,000 Alberta patients experience the major life disruption of neuropathic pain. New knowledge is their greatest hope.

To Albertans:

Relief of pain for those suffering from peripheral nerve damage, whether through diabetes, diseases such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, or injury means a restored quality of life and the ability to stay productively employed.

To the health care system:

An effective first line treatment for peripheral nerve damage would reduce the need for multiple visits to health professionals including neurologists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Zochodne and his team were the first to discover that nerve cells also have molecules responsible for imposing a degree of restraint on growth. This is necessary, he says, as unrestrained growth might cause epilepsy and, in other cells, cancer.

"As it happens, in diabetes, at least with what we've looked at so far, there are elevated levels of PTEN that limits regeneration and repair. If you lower its levels you increase the growth of nerves, so it's an interesting avenue and we think there are a whole series of molecules like this. The idea is to release the restraints on growth and allow robust recovery."

Zochodne has demonstrated the increase of nerve cell regeneration that results from knocking down the level of PTEN in diabetic pre-clinical models. The challenge is to release the brakes on growth in the nerve cells only and in a way that's temporary in order to prevent side effects.

A new class of drugs called siRNA (Small interfering RNA) may be the key to allowing the precise selection of nerve cell PTEN without altering other molecules and ideally not impacting cell growth in other parts of the body.

Zochodne's lab was among the first in the world to investigate the neurological role of PTEN and the first to publish its impact on peripheral nerves in 2010. While their work has major implications for diabetic polyneuropathy, the understanding gained also has implications for nerve damage from injuries and diseases such as Guillain-Barre syndrome.

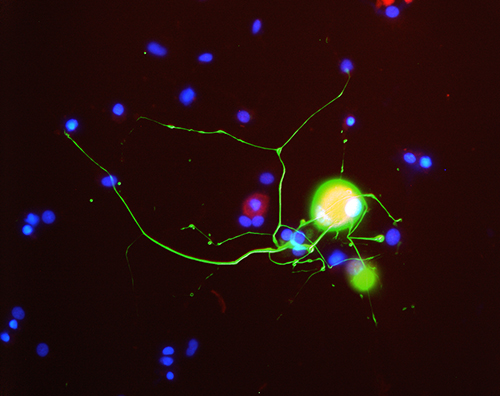

Image of a neuron, courtesy of Zochodne lab

About the U of A's Department of Medicine (DoM):

-

3.5 times each day, DoM researchers publish or present new knowledge to the world.

-

Each year, DoM researchers attract more than $30-million in research funding.

-

Each year, DoM specialists educate more than 600 undergraduate medical students and supervise roughly 90 research trainees and 185 medical residents.

-

Each year, DoM clinical researchers commit their efforts to more than 160 clinical trials, which attract an additional $10-million in funding.