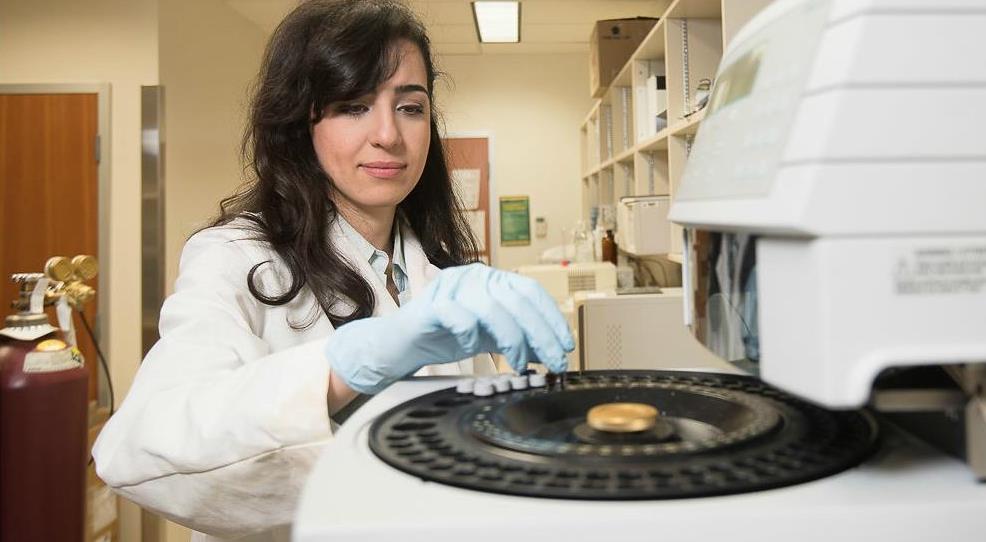

Graduate student Hoda Soleymani always knew she wanted to work in health sciences. She excelled in sciences at an early age and is now researching delivery platforms for cancer drugs.

Even from an early age growing up in her native Iran, graduate student Hoda Soleymani seemed destined to study pharmaceutical sciences.

Her favourite secondary school teachers taught chemistry and physics.

She was among the top 400 chosen from 600,000 students to attend one of the top schools in Tehran. "I had a soft spot for those science topics," says Soleymani, who grew up in Tehran, Iran's capital city. "That's what really drew me to want to pursue a pharmacy degree."

After being accepted into the second best pharmacy school in Tehran, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, she spent the next seven years completing her undergraduate and PharmD degree.

"The program is a combined undergraduate and PharmD program, which is different than Canada or the US," says Soleymani.

In exchange for free tuition, Soleymani committed to working in an impoverished area of Iran after her graduation in 2008. Her two-year experience in a community hospital in a small town convinced her she needed more education.

"I came away with a realization that I needed to learn more to help people," she says. "The patients had a hard time with drug side effects and so, I knew I had to educate myself further and be more up to date on the science of medications."

After researching Canadian and US universities, she decided on the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences to continue her education in 2011. The choice was partly because of the great reputation the University of Alberta enjoyed and a bit of networking.

"My supervisor in Tehran knew Dr. Lavasanifar (Soleymani's supervisor at UAlberta), so that connection was very helpful and the faculty has a great reputation worldwide when it comes to graduate education in pharmaceutical sciences," she says.

She spent the next five-and-a-half years completing her PhD. For her PhD thesis, Soleymani focused on the topic of overcoming drug resistance in breast cancer tumours. "One of the main problems with cancer treatments in general is that patients start to develop a resistance to the chemotherapy," says Soleymani.

She says there are three main reasons for this: in general, people don't get a high concentration of drug inside the tumour, cells by nature are resistant to drugs and some areas of a tumour don't receive enough oxygen and are resistant to cancer drugs.

"The problem is that when you inject a drug into your circulation system, it can go anywhere including healthy tissues, which leads to side effects," she says. "Only a small portion of the treatment drug will reach a tumour, so you won't get a very effective treatment." Soleymani says her research will look at resolving this issue by developing an improved platform to deliver drugs and other genetic material to a targeted area.

"A specific delivery platform will limit the distribution of the drug to just the diseased portion and wouldn't impact health organs reducing side effects," she says. From her early school years in Iran, Soleymani says she has had a several influential people in her life to help her attain her education goals. She believes people can be inspired by anyone in their life.

One of her inspirations is her current supervisor, Afsaneh Lavasanifar. "As a woman in pharmaceutical sciences, I couldn't ask for a better role model. She is very successful but she does it with such grace without being too harsh on the students. Students are willing to meet her high expectations in the lab because there is such a mutual respect between her and her students. She is very supportive of the students."

For Lavasanifar, the respect is mutual. She says Soleymani's strengths include her work habits, her motivation and her curiosity in research. "Hoda has been one of my best graduate students, among the top five per cent in a group of close to 100 students I have encountered during the 15 years of my work as a graduate student supervisor and mentor," says Lavasanifar. "I witnessed Hoda's progress in intellectual, academic and scholarly activities at a fast pace."

When she's not in school, you can find Soleymani practicing her new found sport-kickboxing. She took up the martial art in the last year and approaches it in a scientific way. "I'm not normally a sports person," she says. "The most enticing part for doing martial arts is you are building muscle memory and doing everything in co-ordination and that's very fun for me."

Solyemani successfully defended her PhD in April and her future plans include continuing to research delivery platforms for cancer drugs. After her time at the University of Alberta, she says she plans to complete a two-year post-doctoral fellowship in Montreal.

How did she choose Montreal? "Someone told me when visiting a city, ask yourself, Can I see myself living here?," says Soleymani. "Last time, I visited Montreal, I saw myself living there, so I think it was fate. Sometimes, you want something but the opportunity is not there, so it has to be the right opportunity."