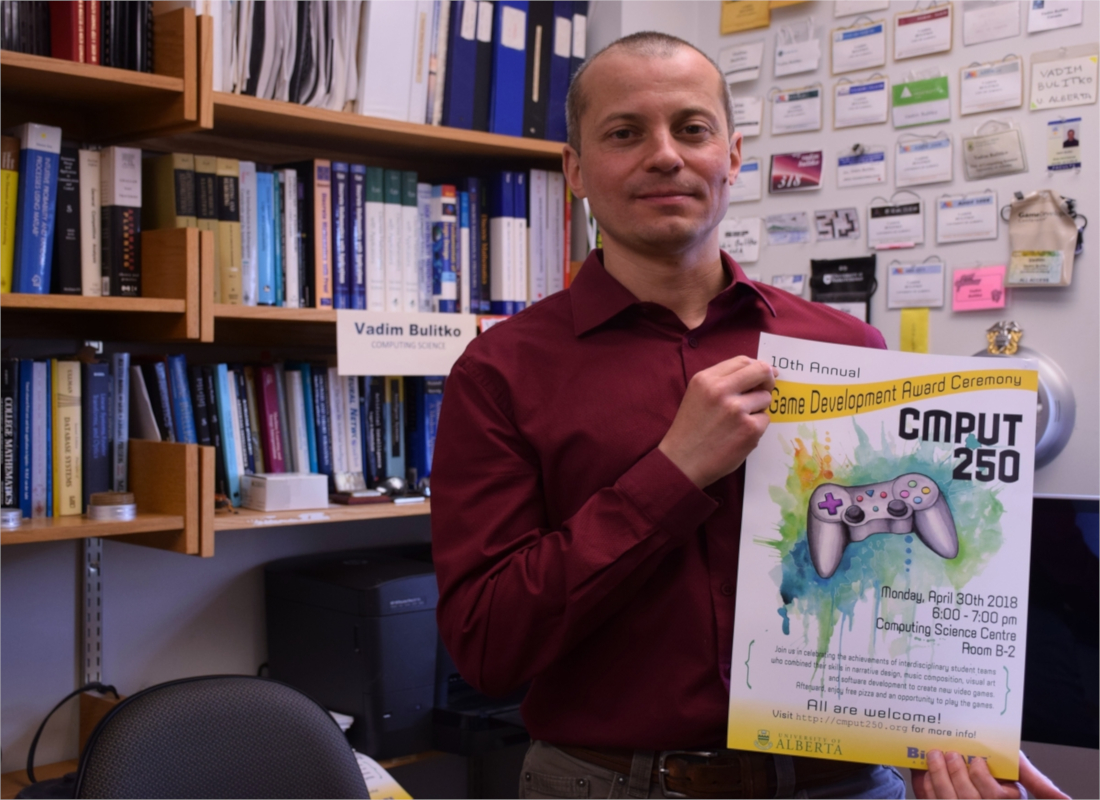

Meet Vadim Bulitko, December 2018 Instructor of the Month and professor in the Department of Computing Science. Photo credit: Michaela Ream

What do you teach?

My main undergraduate class is CMPUT 250, which is Computers and Games. I also teach graduate classes on artificial intelligence.

Why should people learn about these subjects?

Well, for the computers and games course, I think people should learn about these topics given how large the video game industry is and how many people play games-the numbers are staggering. How many households have video games? How many kids play video games? It's a big phenomenon, so understanding and studying topics related to that is important.

The class is not about developing games necessarily-it's about the cultural issues, moral issues, and ethics around it. We've had lectures on harassment related to video games, online culture related to video games-basic kinds of issues that people, millions of people, deal with every day. When something becomes so prominent in society, there are going to be all sorts of ripple effects.

The graduate classes on artificial intelligence have a similar answer. AI is very rapidly becoming a big thing in our society, with everything from Google to Siri or self-driving cars, all sorts of things are happening-it's an interesting time.

What's the coolest thing about these subject areas?

The fact that this is one of the very few classes where students have a big project that is inherently interdisciplinary. You cannot make a game with just artists or musicians or story writers or programmers-you need a team. And this course is the first time where a lot of these undergraduate students get to work on something very demanding and very difficult with students from other disciplines, but also something very rewarding.

They get to interface and work, not just chat over a cup of coffee, but work for hours towards a common objective with people from other disciplines who don't speak their jargon and their own language. And that's both a source of great joy, when it works, and also frustration when it doesn't work-just like in real life. And if you talk to any company about company values, well, they value teamwork because almost everything nowadays is team-based.

Major game studios can feel that they would rather hire a five-star team player who may be not necessarily a five-star technical person, than a five-star technical person who is a one-star team player. Because it's more important to them that a person works on a team, than if they are the absolute best programmer in the world.

For the AI part, I think the coolest thing is that the courses are fairly open-ended. The students get to pick their own projects and they can also work in teams, and they get to do something that they are very passionate about. Maybe they always wanted to plan machinery to do artificial evolution or something-here's the opportunity to do that within this class.

What was it that drew you to this field?

With AI, I always wondered "what intelligence?" Ever since I was a kid it was the biggest mystery to me. What happens in here? What's creativity? What's insight? When I say eureka what does that mean? How does some thought come out of seemingly nothing? You don't have it, don't have it, don't have it and then boom; you wake up and think "I know how to do it." What is this "yes" moment? What does that mean? I've always been wondering about that, and to me artificial intelligence is a way to study that.

AI is kind of the petri dish of this cognition. Other disciplines such, as philosophy for instance, also study that but in their own way. Psychology also studies that, but again in their own way. Whereas in AI, you have this advantage, in my opinion, in which I can say, "okay, if I think I know how to play chess I can write a program and see how well it plays chess. If I think I know what an emotion is and I can describe it precisely enough for a computer to have it, well let's put it in and see if people think the computer becomes emotional." So you can do these computational experiments, so I think that's a cool thing about AI and I encourage my students to take on crazy topics.

Why did I go into video games? Well, I like video games. Personally, I enjoy video games as a way to experience a world which I normally wouldn't be able to. Maybe I'm flying a spaceship or I'm in a post-apocalyptic environment, something that I would not necessarily want to do in real life. So I appreciate the atmosphere, and the story. Much more so than in games like Tetris, which are logical puzzles or reaction games like online shooting, those personally don't interest me as much. But in general, in games it's another world just like literature and movies, except those are more passive because you are just watching a film. You can pause, you can rewind, you can fast forward. But in a game, it won't advance without you being a participant. So that agency or interpretability, I think that attracts lots of people to video games-they feel they are a participant not an observer.

To people who view computer games with a stigma that they are 'just games'-what would you say is the educational value of computer games?

I think there are a few answers to that. One indication of value is interdisciplinary work. To build a video game, to even think about a video game in a deep academic sense, you need people from other disciplines. You need people from cultural studies, you need people from humanities, you need people from computing. So not even to build a video game but to really analyze something like gender issues, equality, racism, discrimination of some sorts, how do we analyze that with respect to video games? You need people from different areas. So to me, the fact that you get to hear different disciplines' takes on a question, that's really insightful because that makes us more well-rounded in our education.

"I think we need to listen, to me that's important, and games are so interdisciplinary and are involved so much in the fabric of our society, they necessarily force an interdisciplinary way of thinking." -Vadim Bulitko

It makes us appreciate other people's viewpoints and I think this is something that definitely helps society; it's not enough to have your own opinion, but instead to at least make an effort to understand what the other party is saying. I think we need to listen, to me that's important, and games are so interdisciplinary and are involved so much in the fabric of our society, they necessarily force an interdisciplinary way of thinking.

This idea that games are this mindless shallow thing, that's a bit outdated in my opinion. Games address all sorts of topics and often very difficult societal issues: alternate history, predictions of the future, how would AI be accepted or not accepted in a society, would people feel scared?

These kinds of things, like any work of fiction, can be studied within games except here again the readers or audiences are interacting. In some ways they can shape the events, and now because games are now so connected online, we can collectively shape the development of the story-not just individually. With thousands of others we're shaping the way the game is advancing; which is not really that different from the way the kind of non-gaming world works-so games have progressed a lot. Is there still violence? Of course, similarly to how there is violence in movies or in books.

What is one thing that people would be surprised to know about you?

I grew up doing a lot of art, painting, oil paintings, writing fiction stories-which I still do, both paintings and stories. I also direct films and I'm a cinematographer on many amateur productions. I have 11 films on IMDB.