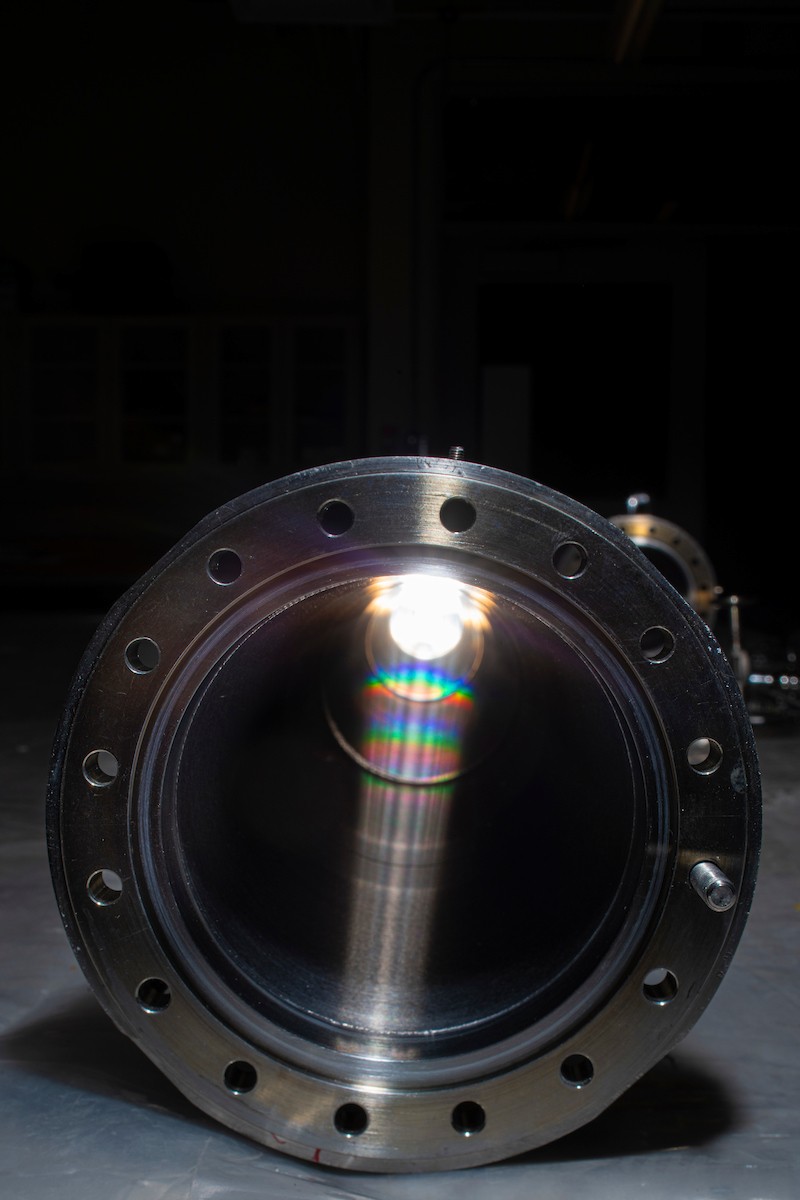

This might look like any other length of pipe, but it's actually a $1 million part inside which the conditions of the Big Bang have been replicated. UAlberta physicists are cutting apart this beampipe in the hunt for magnetic monopoles. Photo credit: John Ulan

Physicists at the University of Alberta are cutting apart a $1 million component of the world's largest particle accelerator in the hunt for something never before documented on Earth-a magnetic monopole.

"When I was a child, I remember wondering what would happen if I cut a magnet in half, trying to separate the poles. Of course, you just end up with two smaller magnets-but what we're looking for is a fundamental magnetic charge with only one pole," said James Pinfold, professor in the Department of Physics who is leading the study. "It's a discovery that would tell us new things about the birth of the universe and change how we explain physics down to the high school textbook level."

A founding member of the ATLAS Experiment at CERN that discovered the long-sought "God particle," the Higgs boson, in 2012, Pinfold is no stranger to exploring new frontiers in particle physics. He is now leading the LHC's newest international experiment, the Monopole & Exotics Detector at the LHC (MOEDAL)-the primary mission of which is to search for the magnetic monopole..

And the hunt for the never-before-seen monopole requires looking in conditions far beyond the ordinary, such as one of the most unusual environments on Earth: inside the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)Large Hadron Collider-the world's largest and most powerful particle accelerator, a 27-kilometre ring of superconducting magnets.

"The component we're taking apart-the beampipe-is the two-and-a-half-metre stretch of pipe that once contained collisions so energetic that they replicated conditions of the Universe as it was roughly a picosecond after the Big Bang," said Pinfold. "When the experiments get above a certain charge, the ionization by a monopole causes it to lose so much energy as it moves through matter that it will never escape the pipe and into the sensors-leaving monopoles trapped in the metal of the pipe."

In the pipeline

To find out for sure, the researchers are cutting apart the beampipe piece by piece. It's an unexpected end to a million-dollar component-precision-machined from ultralight material to avoid interfering with detection. But as Pinfold explains, it's a way to yield one last burst of science from a retired part.

"This pipe had ended up as a spare for a spare, as the parts need to be reconfigured for new experiments, and the team of the Compact Muon Solenoid at CERN graciously allowed us to use it." said Pinfold. "It is reminiscent of the Cassini probe that NASA intentionally burned up in Saturn's atmosphere in 2017: a part at the end of its operational lifespan being used, in a catastrophic way, to learn something new."

Pinfold and his team will carry out the disassembly of the beampipe this summer and begin their analysis-but even if they don't find the first-ever monopole, the experiment will advance our knowledge of particle physics.

"You hope for the big discovery, of course. But when you're pushing the boundaries of our knowledge of particle physics, not finding something can tell us a lot as well," said Pinfold. "We can set limits on where we know that monopoles aren't created-and that guides where we push future experiments to look for them."

"But we've got our fingers crossed."