One of the principal difficulties in the reconstruction of Northwest Coast (NWC) language families is the tremendous time-depth that must be posited to make any kind of case for genetic relationships between languages of the various families, time-depths which rival or even exceed those proposed for the more familiar examples of Indo-European and Afro-Asiatic. In the absence of written historical records, however, the task of reconstruction on the Northwest Coast has been much more problematical than the reconstruction of Indo-European, which was aided by diverse and extensive attestation of lexical material and grammatical patterns from the intermediate ancestors of the modern PIE daughter languages. Without such aids, establishing deep genetic affiliations on the NWC by means of the traditional historical comparative method is a slow and arduous task, and, rather than relying on historical reconstruction, a number of investigators have attempted to create genetic groupings based on typological similarities between languages of the different families--which, after all, were the original sources of the intuition that such relationships might exist. One of the most famous of these attempts is Edward Sapir's Na-Dene hypothesis--linking Haida, Tlingit, Eyak, and Athapaskan, largely on the basis morphological similarities--and this hypothesis, in turn, sparked one of the most famous debates in Amerindian historical linguistics between Sapir and Franz Boas, who argued that such typological similarities could as well be attributed to diffusion as to common descent.

The Central Northwest Language Area

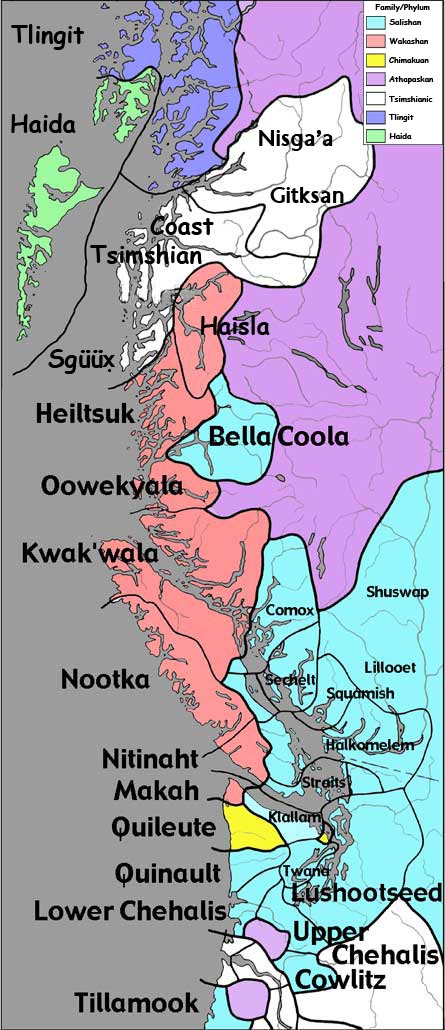

Another of Sapir's controversial genetic groupings was the Mosan phylum, under which he tried to subsume three well-established stocks—Salishan, Chimakuan, and Wakashan—found in the Central Northwest language area encompassing southern British Columbia and northern Washington State. Like the Na-Dene phylum, the Mosan grouping was based largely on intuition and a smattering of lexical borrowings observed in languages of the three families; Sapir himself did little to defend Mosan, that task being undertaken most thoroughly by his student Morris Swadesh (1953a, 1953b, 1953c). Swadesh's (1953a) most impassioned defense of the Mosan hypothesis is highly similar to Sapir's case for Na-Dene in that it relies more heavily on typological data and instances of phonological and morphosyntactic similarities than it does on lexical comparison and reconstruction, the normal grist for the historical comparative mill, and Swadesh's argument hinges crucially on the assumption that, unlike lexical material, at least some types of morphosyntax are impervious to cross-linguistic borrowing. However, recent studies of the transmission and spread of typological and grammatical features in situations of language contact, particularly Thomason & Kaufman (1988) and Nichols (1992), cast serious doubt on Swadesh's contention that the similarities he has drawn among the Mosan languages are, in fact, evidence of "remote common origin", and careful examination of the similarities that he documents in the Mosan languages reveals that these features appear in other languages of the NWC as well—languages that are clearly not genetically linked to the languages of the putative Mosan family at any reconstructable time-depth.

That said, the fact remains that the languages of the Salish, Wakashan, and Chimakuan families do present a picture of remarkable grammatical similarity, even within the context of the NWC Coast as a whole, which in itself shows the extensive signs of transmission of phonological, morphological, and syntactic patterns typical of a Sprachbund. In this paper, I examine Swadesh's evidence for the Mosan hypothesis and argue that these similarities and other grammatical patterns common to the languages of the Central Coast running from north-western Washington to the central coast of British Columbia are evidence, not for a genetic grouping, but for an areal-typological grouping of languages that unites the members of the three families.

References

Nichols, Johanna. 1992. Linguistic diversity in space and time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sherzer, Joel. 1976. An area-typological study of American Indian languages north of Mexico.New York: North Holland.

Suttles, Cameron, and Wayne Suttles. 1985. Native languages of the Northwest Coast.Map published by The Oregon Historical Society.

Swadesh, Morris. 1953a. Mosan I: A problem of remote common origin. International Journal of American Linguistics19, 26 - 44.

Swadesh, Morris. 1953b. Mosan II: A problem of remote common origin. International Journal of American Linguistics19, 223 - 36.

Swadesh, Morris. 1953c. Salish-Wakashan comparisons noted by Boas. International Journal of American Linguistics19, 290 - 291.

Thomason, Sarah, and Terence Kaufman. 1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics.Berkeley: University of California Press.

Thompson, Laurence C., and M. Dale Kinkade. 1990. Languages. Handbook of the North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast,ed. by Wayne Suttles, 30 - 51. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.