Coxe and Williams in Switzerland

extracts from Romanticism CD for class sessions on

February 1, 3

illustrations rescanned (but for details of prints see CD)

William Coxe, Sketches of the Natural, Civil, and Political State of Swisserland; in a series of Letters to William Melmoth, Esq. (London: J. Dodsley, 1779).

Helen Maria Williams, A Tour in Switzerland; or, A view of the present state of the Government and Manners of those Cantons: with comparative sketches of the present state of Paris, 2 vols. (London: G. G. and J. Robinson, 1798).

Extracts

1. Williams: introductory

2. Rhine Falls, Schaffhausen (parallel texts)

3. Urnersee (Lake of Uri) (parallel texts)

4. Ascent to the St. Gotthard: Coxe, Williams

5. Glaciers: Coxe (Chamonix), Williams (Rheinwald)

1. Williams: introductory

[Vol. I, i] In presenting to the Public a View of Switzerland, a country of which so much has already been written, it may perhaps become me to clear myself from the charge of presumption. The descriptive parts of this journal were rapidly traced with the ardor of a fond imagination, eager to seize the vivid colouring of the moment ere it fled, and give permanence to the emotions of admiration, while the solemn enthusiasm beat high in my bosom; but when the sensations excited by those views of majestic grandeur had subsided, I recollected, with regret, that the paths which I had delighted [ii] to tread had been trodden before; and that the objects on which I had gazed with astonishment had been already described. It is true, that the sketch I have penciled of that sublime scenery, however rude, will be found to be an original drawing, copied from nature, and not from books; yet I should scarcely have presumed to obtrude that unfinished outline on the public eye, if the other parts of my journal offered nothing new to its observation. . . . [refers to political commentary]

[4] [Basle] The first view of Switzerland awakened my enthusiasm most powerfully

-- "At length," thought I, "am I going to contemplate that interesting country,

of which I have never heard without emotion! -- I am going to gaze upon images

of nature; images of which the idea has so often swelled my imagination, but

which my eyes have never yet beheld. -- I am going to repose my wearied spirit

on those sublime objects -- to sooth my desponding heart with the hope that

the moral disorder I have witnessed shall be rectified, while I gaze on nature

in all her admirable perfections; and how delightful a transition shall I

find in the picture of social happiness which Switzerland presents! I shall

no longer see [5] liberty profaned and violated; here she smiles upon the

hills, and decorates the vallies, and finds, in the uncorrupted simplicity

of this people, a firmer barrier than in the cragginess of their rocks, or

the snows of their Glaciers!"

|

Williams

|

|

|

|

|

|

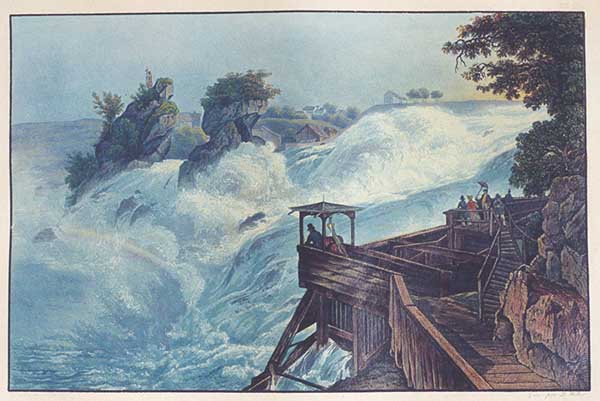

[16] This morning we set out on horseback, in order to see the fall of the Rhine at Lauffen, about a league from this place. Our road lay over the hills which form the banks of the Rhine; from whence we had some fine views of the town and castle of Schaffhausen: the environs are picturesque and agreeable; the river beautifully winding through the vale. Upon our arrival at Lauffen, a small village in the canton of Zuric, we dismounted; and advancing to the edge of the [17] precipice which overhangs the Rhine, we looked down perpendicularly upon the cataract, and saw the river tumbling over the sides of the rock with amazing violence and precipitation. From hence we descended till we were somewhat below the upper bed of the river, and stood close to the fall; so that I could almost have touched it with my hand. A scaffolding is erected in the very spray of this tremendous cataract, and upon the most sublime point of view:-- the sea of foam tumbling down--the continual cloud of spray scattered around at a great distance, and to a considerable height--in short, the magnificence of the whole scenery far surpassed my most sanguine expectations, and exceeds all description. Within about an hundred feet, as it appeared to be, of the scaffolding, there are two rocks in the middle of the fall, that prevent one from seeing its whole breadth from this point: the nearest of these was perforated by the [18] continual action of the river; and the water forced itself through in an oblique direction, with inexpressible fury, and an hollow sound. After having continued some time, contemplating in silent admiration the awful sublimity of this wonderful landscape, we descended; and below the fall we crossed the river, which was exceedingly agitated. Hitherto I had only viewed the cataract sideways; but here it opened

by degrees, and displayed another |

[Vol. I, 59] When we reached the summit of the hill which leads to the fall of the Rhine, we alighted from the carriage, and walked down the steep bank, whence I saw the river rolling turbulently over its bed of rocks, and heard the noise of the torrent, towards which we were descending, increasing as we drew near. My heart swelled with expectation--our path, as if formed to give the scene its full effect, concealed for some time the river from our view; till we reached a wooden balcony, projecting on the edge of the water, and whence, just [60] sheltered from the torrent, it bursts in all its overwhelming wonders on the astonished sight. That stupendous cataract, rushing with wild impetuosity over those broken, unequal rocks, which, lifting up their sharp points admidst its sea of foam, disturb its headlong course, multiply its falls, and make the afflicted waters roar--that cadence of tumultuous sound, which had never till now struck upon my ear--those long feathery surges, giving the element a new aspect--that spray rising into clouds of vapour, and reflecting the prismatic colours, while it disperses itself over the hills--never, never can I can forget the sensations of that moment! when with a sort of annihilation of self, with every past impression erased from my memory, I felt as if my heart were bursting with emotions too strong to be sustained.--Oh, majestic torrent! which hast conveyed a new image of nature to my soul, the moments I have [61] passed in contemplating thy sublimity will form an epocha in my short span!--thy course is coeval with time, and thou wilt rush down thy rocky walls when this bosom, which throbs with admiration of thy greatness, shall beat no longer! What an effort does it require to leave, after a transient glimpse, a scene on which, while we meditate, we can take no account of time! its narrow limits seem too confined for the expanded spirit; such objects appear to belong to immortality; they call the musing mind from all its little cares and vanities, to higher destinies and regions, more congenial than this world to the feelings they excite. I had been often summoned by my fellow-travellers to depart, had often repeated "but one moment more," and many "moments more" had elapsed, before I could resolve to tear myself from the balcony. [62] We crossed the river, below the fall, in a boat, and had leisure to observe the surrounding scenery. The cataract, however, had for me a sort of fascinating power, which, if I withdrew my eyes for a moment, again fastened them on its impetuous waters. In the back-ground of the torrent a bare mountain lifts its head encircled with blue vapours; on the right rises a steep cliff, of an enormous height, covered with wood, and upon its summit stands the Castle of Lauffen, with its frowning towers, and encircled with its crannied wall; on the left, human industry has seized upon a slender thread of this mighty torrent in its fall, and made it subservient to the purposes of commerce. Founderies, mills, and wheels, are erected on the edge of the river, and a portion of the vast bason into which the cataract falls is confined by a dyke, which preserves the warehouses and the neighbouring huts from its inundations. [63] Sheltered within this little nook, and accustomed to the neighbourhood of the torrent, the boatman unloads his merchandize, and the artisan pursues his toil, regardless of the falling river, and inattentive to those thundering sounds which seem calculated to suspend all human activity in solemn and awful astonishment; while the imagination of the spectator is struck with the comparative littleness of fleeting man, busy with his trivial occupations, contrasted with the view of nature in all her vast, eternal, uncontrolable grandeur. |

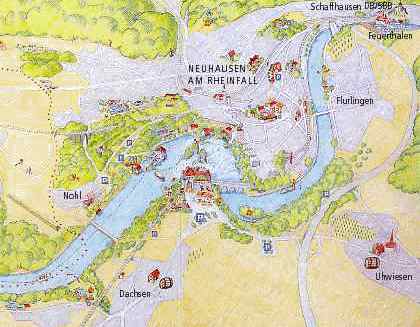

Map

(from http://www.rhinefalls.com/umgebungsplan.html).

Coxe and Williams approached the Falls from the south at Laufen Castle,

where scaffolding provided a close approach to the cascade; they then

crossed the river below the falls to the north bank. Map

(from http://www.rhinefalls.com/umgebungsplan.html).

Coxe and Williams approached the Falls from the south at Laufen Castle,

where scaffolding provided a close approach to the cascade; they then

crossed the river below the falls to the north bank. |

|

|

[132] [Continuing trip down Lake Lucern by boat] Towards the end of this branch the lake forms a considerable bay; in the midst of which lies the village of Brunnen, celebrated for the signing of the treaty, in 1315, between Uri, Schweitz, and Underwalden. From this point we had a glimpse of Schweitz, the capital burgh of the canton, about two miles from Brunnen: it stands farther within the land, at the bottom of two very high, sharp, and rugged rocks. Here we turned short to our right-hand and entered the third branch, or the lake of Uri; the scenery of which is so amazingly grand and sublime, that the impression it made upon me will never [133] be erased from my mind. Imagine to yourself a deep and narrow lake about nine miles in length, bordered on both sides with rocks uncommonly wild and romantic, and, for the most part, perpendicular; with forests of beech and pine growing down their sides to the very edge of the water: indeed the rocks are so entirely steep and overhanging, that it was with difficulty we could observe more than four or five spots, where we could have landed. On the right-hand, upon our first entrance, a detached piece of rock, at a small distance from the shore engaged our attention. It rises to about sixty feet in heighth; is covered with brushwood and shrubs; and reminded me in some degree of those that shoot up in the middle of the fall of the Rhine near Schaffhausen: but here the lake was as smooth as chrystal; and the silent, solemn gloom which reigned in this place, was not less awful and affecting than the tremendous [134] roaring of the cataract in the other. Somewhat further, upon the highest point of the Seeliburg, we observed a small chapel that seemed inaccessible; and below it, the little village of Gruti, near which the three heroes of these cantons are said to have met, and to have taken reciprocal oaths of fidelity, when they planned the famous revolution. On the opposite side, but farther on, appears the chapel of William

Tell, erected in honour of that hero, and upon the very spot where (it

is said) he leaped from the boat, in which he was carrying prisoner

to Kussnacht. It is built upon a rock that juts out into the lake under

a hanging wood: a situation amid scenes so strikingly awful, as cannot

fail of strongly affecting even the most dull and torpid imagination!

|

[Vol. I, 141] No place could surely be found more correspondent to

a great and generous purpose, more worthy of an heroical and sublime

action, than the august and solemn scenery around us. The Lake which

we had traversed nearly from west to east, turns direct from the point

opposite Brunen to the south, and is said to be in this part six or

seven hundred feet deep. This branch is called the Beneath their inaccessible ramparts, whose enormous height gives an appearance of narrowness to the lake, we sailed, gazing with that kind of rapt astonishment which fears to disturb, or be disturbed by the mutual communication of thought. The approach of night spread new forms of shadowy greatness over the scene. We had loitered many hours on our passage, forgetting that the last part of our voyage was the most perilous. But the unruffled stillness of the water, the delicious serenity of the evening, and the long reflected rays of the moon from the whitened summits of the opposite mountains, of which we sometimes [143] caught a glimpse, dissipated every idea of danger. The only sounds that broke the awful silence were the gentle motion of the oars of our wearied boatmen, and the tolling of the distant bell from Altorf, borne down the lake, and

We had passed through all the soft gradations of twilight, and had enjoyed the brownest horrors of evening in all their deepening gloom, before the moon had scaled the lofty summits which concealed her from our view. At length she burst upon us in her fullest radiancy, illumining the dusky sides of the cragged rocks, and the dark foliage of the piny woods; burnishing with her silver rays the smooth and limpid waters; shooting her shadowy beams along the lake to the distant perspective [144] of the mountains we had left behind; and lighting up the whole majestic scenery with glorious and chastened lustre.

|

Coxe

[156] We quitted Altdorf after dinner, having with difficulty hired two horses,

besides one for the baggage; we procured, however, another upon the road:

so that what with riding and tying we got on very well. About nine miles from

Altdorf, we began ascending. The road winds continually along the steep sides

of the mountains; and the Reuss in many places entirely fills up the bottom

of the valley, which is very narrow: that river sometimes appeared several

hundred yards below us; here rushing a considerable way through a forest of

pines; there falling down in cascades, and losing itself in the valley. We

passed it several times over bridges of a  single

arch, and beheld it tumbling under our [157] feet in channels which it had

forced through the solid rock; innumerable torrents roaring down the sides

of the mountains; which were sometimes bare, sometimes finely wooded, with

here and there some fantastic beeches hanging on the sides of the precipice,

and half obscuring the river from our view. The darkness and solitude of the

forests; the occasional liveliness and variety of the verdure; immense fragments

of rock blended with enormous masses of ice, that had tumbled from the mountains

above; rocks of an astonishing heighth piled upon one another, and shutting

in the vale; -- such are the sublime and magnificent scenes with which this

romantic country abounds, and which enchanted us beyond expression.

single

arch, and beheld it tumbling under our [157] feet in channels which it had

forced through the solid rock; innumerable torrents roaring down the sides

of the mountains; which were sometimes bare, sometimes finely wooded, with

here and there some fantastic beeches hanging on the sides of the precipice,

and half obscuring the river from our view. The darkness and solitude of the

forests; the occasional liveliness and variety of the verdure; immense fragments

of rock blended with enormous masses of ice, that had tumbled from the mountains

above; rocks of an astonishing heighth piled upon one another, and shutting

in the vale; -- such are the sublime and magnificent scenes with which this

romantic country abounds, and which enchanted us beyond expression.

We set out this morning early from Wasen, a small village where we passed the night; and continued advancing for some way on a rugged ascent, through the same wild and beautiful tract of [158] country, which I have just mentioned. We could scarce walk an hundred yards without crossing some of those torrents, that precipitated with violence from the tops of the mountains in different forms; the water clearer than chrystal. The road, exceedingly steep and craggy, is chiefly paved: in many places it is carried upon arches under a high mountain, and overhangs a deep precipice; the river roaring and foaming below. This being one of the great passages into Italy, we met a considerable number of pack-horses laden with merchandize: and as the road in particular parts is very narrow, it required some dexterity in the horses to pass one another without jostling. These roads, hanging as they do over the precipice, cannot fail of inspiring terror to those travellers, who are unaccustomed to them; and more particularly as the mules and horses have a singular method of going on. They do not keep in the middle of the track, [159] but continue crossing from the side of the mountain towards the edge of the precipice, then turn aslant abruptly; and thus form, if I may so express myself, a constant zig-zag.

Thus far the valley of St. Gothard appeared to be well peopled; and we passed

through several villages situated towards the bottom and less narrow part

of the valley: the sides of the mountains were occasionally strewed thick

with cottages; covered with forests; or enriched with pastures. Still continuing

to ascend, the country a little beyond Wasen suddenly changed.  It

now became more wild and perfectly desert: there were no traces of any trees,

except here and there a stubbed pine; the rocks were more bare, craggy, and

impending; not the least sign of any habitation; and scarce a blade of grass

to be seen. We then came to a

It

now became more wild and perfectly desert: there were no traces of any trees,

except here and there a stubbed pine; the rocks were more bare, craggy, and

impending; not the least sign of any habitation; and scarce a blade of grass

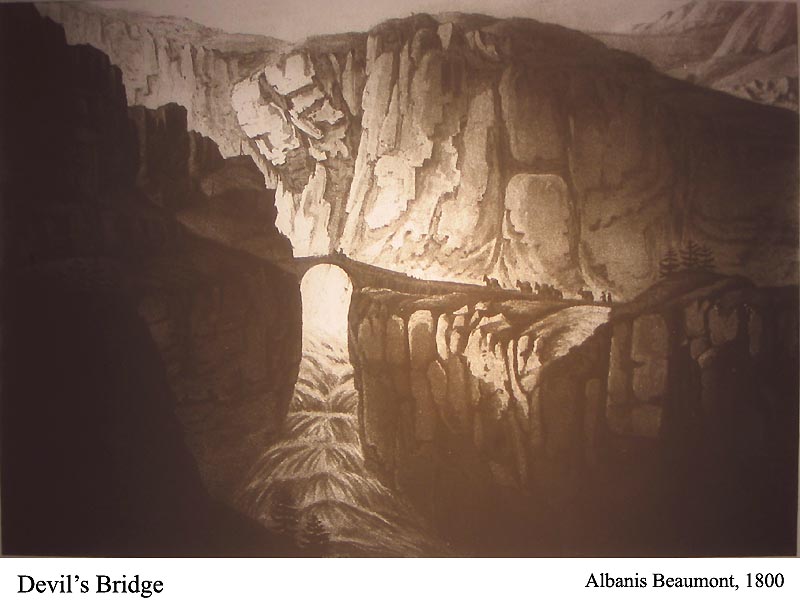

to be seen. We then came to a  bridge

thrown across a very deep chasm over the Reuss, which here forms a [160] considerable

cataract down the shagged sides of the mountain, and over immense fragments

of rock which it has undermined in its course. This bridge is called Teufels-bruck,

or the devil's bridge; the common people always attributing works of any difficulty

to the devil. As we stood upon the bridge admiring the cataract, we were covered

with a kind of drizzling rain; the river throwing up the spray to a considerable

heighth. These are sublime scenes of horror, of which those who have not been

spectators, can form no idea: neither the powers of painting nor poetry can

give an adequate image of them.

bridge

thrown across a very deep chasm over the Reuss, which here forms a [160] considerable

cataract down the shagged sides of the mountain, and over immense fragments

of rock which it has undermined in its course. This bridge is called Teufels-bruck,

or the devil's bridge; the common people always attributing works of any difficulty

to the devil. As we stood upon the bridge admiring the cataract, we were covered

with a kind of drizzling rain; the river throwing up the spray to a considerable

heighth. These are sublime scenes of horror, of which those who have not been

spectators, can form no idea: neither the powers of painting nor poetry can

give an adequate image of them.

Not far from this wonderful landscape (the country still continuing solitary and desolate) the road led us into a subterraneous passage, of about eighty paces in length, cut through a rock of granite, which opened at the opposite entrance into the serene and [161] cultivated valley of Urseren: the objects that presented themselves to us were, a village backed by an high mountain, on the sides of which was a wood of pines; peasants at work in the fields; cattle feeding in the meadows; and the river, which, when we last saw it, loudly dashed over rude fragments of rock in a continual cataract, now flowed silently and smoothly along; while the sun, which had been hidden from us when we were in the deep valley, here shone forth in its full splendour. In general we had hitherto always found a gradual advance from extreme wildness to high cultivation; but in the present instance, the change was so abrupt and instantaneous, that it seemed like a sudden enchantment.

Williams

[Vol. I, 148] After leaving Altorf, we journeyed along a valley of three leagues, through which the Reuss flows with the ordinary rapidity of a Swiss river.

[149] . . . The rocks, clothed at intervals with trees of various sorts rose high and steep on each side of the valley, which wore a fertile and smiling appearance till we came to the village of Stag; above which the Alps first lift their majestic heads. Here we began to ascend that mass of mountains, which is rather the base than the mountain itself of St. Gothard. The road suddenly becomes so [150] steep, that it required at first some address to keep a seat on horseback. The river, which glided gently through the valley on its expanded bed, being now hemmed in by rocks, begins to struggle for its passage at a profound depth. The pine-clad hills rose on each side to our furthest ken, down which torrent streams were rushing, and crossed our way to mingle themselves with the Reuss, which continually presented new scenes of wonder. The mountains seemed to close upon us as we advanced, sometimes but just space enough was left to admit the passage of the river foaming through the rocks, which seem obstinately to oppose its passage. The road lay for a considerable length on the left side of the precipices, from which we beheld the struggles of the waters, and the tremendous succession of cascades which they formed. An abrupt precipice, forbidding the continuance of the road on this side, a bridge of hardy construction [151] led to the opposite mountain, which is ascended, till meeting with a similar obstruction, we crossed the stream again to the left.

On one of these bridges, we halted to gaze upon the scene around us, and the yawning gulph below. The depth is so tremendous, that the first emotion, in looking over the bridge is that of terror, lest the side should fall away and plunge you into the dark abyss; and it requires some reflection to calm the painful turbulence of surprise, and leave the mind the full indulgence of the sensations of solemn enthusiastic delight, which swell the heart, while we contemplate such stupendous objects.

The name of this bridge, in the language of the country, is the Priest's leap; whether the holy man leapt over the gulph, or into it, is not remembered, but it is difficult to [152] hear the story on the spot without an involuntary shudder, or fancy yourself in perfect security,

The very place puts toys of desperation,

Without more motive into every brain,

That looks so many fathoms to the gulph,

And hears it roar beneath.

Shakespeare. [adapted from Hamlet, I.iv.75-80]

The road up to the village of Wassen is highly romantic: . . . [153] We could yet see no traces of snow, except in the numerous torrents which rolled down the enormous mountains, the streams of which were considerably increased from a cause that in less mountainous countries would have produced an opposite effect, the excessive heat and dryness of the weather, which melted the snows of the Glaciers.

The views around Wassen are astonishing for their variety as well as beauty. You [154] perceive, however, after passing the village, that you are advancing into a country where man is obliged to be continually at war with nature. On one side the mountain was stripped of its piny clothing to some extent, discovering, instead of dark green foliage, a bare rocky and gravelly waste, interspersed with wrecks of trees. This, we were told, was the ravage of an avalanche. When whole forests of majestic height are swept away with irresistible fury, what means of defence can human force oppose to such mighty destruction? Men, however, live tranquilly amidst the danger, and build their houses in such positions, and after such a construction, that the enemy, even if he chances to take the direction of their habitations, may pass over them unhurt.

Rocks, for the most part, are made their allies against these invasions from the snowy [155] mountains; but even rocks, coeval with time, often yield to the terrible devastation. As we advanced, the country, which had hitherto presented scenes of blended grace and majesty, began to assume an aspect of savage wildness and terror. A few habitations and green spots amidst these deserts, gave still some relief to the piece; but after passing the little village of Gestinen, and the torrent of the Meyen which crosses the road to increase the waters of the Reuss, all is tremendous and awful. Here no pines wave their lofty heads, no mountain shrubs display their simple flowrets, nor does even a blade of weed betray the possibility of existence to any things that breathes.

It was now the most luxuriant part of summer; we had left the glowing harvests beneath ripe for the sickle, and the fruits at two or three leagues distance hung in lavish clusters upon the bough; but in this region [156] it not only was winter, but a winter that seemed here to have fixed its eternal abode; for not only were there no traces of renovation to inspire hope, but the impossibility of change was every where obdurately marked. Immense piles of naked rock, not less lofty than the mountains along which we passed, rose sometimes perpendicularly above our heads, and sometimes falling back, left between the road and their horrid tops immense masses that seemed shivered from their sides, forming vast fields of rock.

This passage, which in summer is sufficiently terrific, becomes dangerous in winter by the frequent avalanches that rush from those tremendous heights, and so delicately are these messengers of destruction hung on the summits, that the guides and mule-drivers tye up the bells of their cattle to prevent the gingling, and forbid a word [157] to be spoken by the passengers, that the avalanche, which waits on the mountain to overwhelm them, may not hear them approach. Little crosses placed by the road side where travellers have perished, are melancholy mementoes of such mortal accidents, against which, however, precautions are taken, by firing muskets to shake the air and precipitate the impending avalanche. Huge fragments of rocks sometimes present themselves as if they threatened to obstruct the way; and we remarked one enormous piece of beautiful granite that skirted the raod, and is called the devil's stone, which, on account of some misunderstanding with the people of the country, he brought down from the mountain to destroy some of the works he had himself formerly constructed.

If any superstition is pardonable, it is that of the inhabitants of this mountain, [158] and had the epic poets from Homer, down to our sublime Milton, seen this valley of Schellinen before they described their Tartarus or Pandemonium, they would have caught some new images of the savage and terrific, and their hells would have been habitations less desirable.

The devil of this country, however, cannot, in the estimation of the rude mountaineers, be the same malignant mischievous fiend which the inhabitants of plains and civilized countries make him, since, if he has chosen this chaos of nature for his habitation, he has not shut up his palace, like other stately monarchs, from the vulgar eye, but, on the contrary, has unfolded the recesses of his dwelling by opening ways, and building bridges, which the mountaineers believe none but himself could have constructed, and by which he has certainly "deserved well of the country."

[159] Nothing can be imagined more bold and daring than the road that leads through the valley of Schellenen to the mountain of St. Gothard; the difficulties appear almost insurmountable; sometimes the road seems so narrow between frightful precipices on each side, that great blocks of granite are placed on the edges as safeguards to the passengers; and where the mountain forbids all possibility of passage, offering an impenetrable rampart by its vertical abruptness, the path juts out from the side supported by arches and pillars, which are built up from some salient points of the mass beneath, and seems "a ridge of pendant rock over the vexed abyss" [Milton, Paradise Lost, X, 313-4].

This

road, the breadth of which differs according to the facility of construction,

is in some places from twelve to fifteen feet wide, and in others only ten,

leaving in general space enough for loaded mules to [160] pass each other;

it is paved the greatest part of the way with granite, and is compared, by

Mr. Raymond, to a ribband thrown negligently over the mountains.

This

road, the breadth of which differs according to the facility of construction,

is in some places from twelve to fifteen feet wide, and in others only ten,

leaving in general space enough for loaded mules to [160] pass each other;

it is paved the greatest part of the way with granite, and is compared, by

Mr. Raymond, to a ribband thrown negligently over the mountains.

After winding for some time among these awful scenes, of which no painting can give an adequate description, and of which an imagination the most pregnant in sublime horrors could form but a very imperfect idea, we came within the sound of these cataracts of the Reuss which announced our approach towards another operation of Satanic power, called the Devil's Bridge. We were more struck with the august drapery of this supernatural work, than with the work itself. It seemed less marvellous than expectation had pictured it, and we were perhaps the more disappointed, as we remembered that "the wonderous art pontifical" [Milton, Paradise Lost, X, 312-3], was a part of architecture with which his infernal majesty was [161] perfectly well acquainted; and the rocks of the valley of Schellenen were certainly as solid foundations for bridge building as "the aggregated soil solid, or flimsy," which was collected amidst the waste of chaos, and crouded drove "from each side shoaling towards the mouth of hell." [Milton, Paradise Lost, X, 288.]

Devil's

Bridge. Albanis Beaumont, Travels from France to Italy, through the Lepontine

Alps, etc. London: S. Hamilton, 1800; facing page 212.

Devil's

Bridge. Albanis Beaumont, Travels from France to Italy, through the Lepontine

Alps, etc. London: S. Hamilton, 1800; facing page 212.

On this spot we loitered for some time to contemplate the stupendous and terrific scenery. The mountainous rocks lifted their heads abrupt, and appeared to fix the limits of our progress at this point, unless we could climb the mighty torrent which was struggling impetuously for passage under our feet, after precipitating its afflicted waters with tremendous roar in successive cascades over the disjointed rocks, and filling the atmosphere with foam.

Separating ourselves with reluctance [162] from these objects of overwhelming greatness, we turned an angle of the mountain at the end of the bridge, and proceeded along a way of difficult ascent, which led to a rock that seemed inflexibly to bar our passage. A bridge fastened to this rock by iron work, and suspended over the torrent, was formerly the only means of passing, but numerous accidents led the government to seek another outlet. The rock being too high to climb, and too weighty to remove, the engineer took the middle way, and bored a hole in the solid mass two hundred feet long, and about ten or twelve feet broad and high, through which he carried the road. The entrance into this subterraneous passage is almost dark, and the little light that penetrates through a crevice in the rock, serves only to make its obscurity more visible. Filled with powerful images of the terrible and sublime, from the enormous objects which I had been contemplating [163] for some hours past, objects, the forms of which were new to my imagination, it was not without a feeling of reluctance that I plunged into this scene of night, whose thick gloom heightened every sensation of terror.

After passing through this cavern, the view which suddenly unfolded itself

appeared rather a gay illusion of the fancy than real nature. No magical wand

was ever fabled to shift more instantaneously the scene, or call up forms

of more striking contrast to those on which we had gazed. On the other side

of the cavern we seemed amidst the chaos or the overthrow of nature; on this

we beheld her drest in all the loveliness of infancy or renovation, with every

charm of soft and tranquil beauty. The rugged and stony interstices between

the mountain and the road were here changed into smooth and verdant paths;

the abrupt [164] precipice and shagged rock were metamorphosed into gently

sloping declivities; the barren and monotonous desert was transformed into

a fertile and smiling plain.  The

long resounding cataract, struggling through the huge masses of granite, here

became a calm and limpid current, gliding over fine beds of sand with gentle

murmurs, as if reluctant to leave that enchanting abode.

The

long resounding cataract, struggling through the huge masses of granite, here

became a calm and limpid current, gliding over fine beds of sand with gentle

murmurs, as if reluctant to leave that enchanting abode.

Near the middle of this delicious valley, called the Vale of Urseren, is the village of In-der-Malt [Andermatt], which appeared to have been lately built: behind it was a small forest of pine trees, which are preserved with so much care as a rampart against the avalanches, that the sacred wood was not held more inviolate; and we were told, that the profanation of the axe on this palladium would be followed with the death of the sacrilegious offender.

5.

Glaciers

5.

Glaciers

Coxe at Chamonix

[286]

August 23d, (the day of our arrival at Chamouny) we mounted by the side of

the glacier of Bosson, in order to see les Murailles de glace, so called

from their resemblance to walls: they consist of large ranges of ice of prodigious

thickness and solidity, rising abruptly from their base, and parallel to each

other. Some of these ranges appeared to us about an hundred and fifty feet

high; but if we may believe our guides, [287] they are four hundred feet above

their real base. Near them were pyramids and cones of ice of all forms and

sizes, and shooting up to a very considerable heighth, in the most beautiful

and fantastic shapes imaginable. From this glacier, which we crossed without

much difficulty, we had a fine view of the vale of Chamouny.

[286]

August 23d, (the day of our arrival at Chamouny) we mounted by the side of

the glacier of Bosson, in order to see les Murailles de glace, so called

from their resemblance to walls: they consist of large ranges of ice of prodigious

thickness and solidity, rising abruptly from their base, and parallel to each

other. Some of these ranges appeared to us about an hundred and fifty feet

high; but if we may believe our guides, [287] they are four hundred feet above

their real base. Near them were pyramids and cones of ice of all forms and

sizes, and shooting up to a very considerable heighth, in the most beautiful

and fantastic shapes imaginable. From this glacier, which we crossed without

much difficulty, we had a fine view of the vale of Chamouny.

The 24th. We had proposed sallying forth this morning very early, in order to go to the valley of ice, in the glacier of Montenvert, and to penetrate as far [288] as the time would admit; but the weather proving cloudy, and likely to rain, we deferred setting out till nine, when appearances gave us the hope of its clearing up. Accordingly we procured three excellent guides, and ascended on horseback some part of the way over the mountain which leads to the glacier above mentioned: we were then obliged to dismount, and scrambled up the rest of the mountains (chiefly covered with pines) along a steep and rugged path, called "the road of the chrystal-hunters." From the summit of the Montenvert we descended a little to the edge of the glacier; and made a refreshing meal upon some cold provision which we brought with us. A large block of granite, called "La pierre des Anglois," served us for a table; and near us was a miserable hovel, where those, who make expeditions towards Mont Blanc, frequently pass the night. The scene around us was magnificent [289] and sublime; numberless rocks rising boldly above the clouds, (some of whose tops were bare, others covered with snow.) Many of these gradually diminishing towards their summits, end in sharp points: and from this circumstance they are called the Needles. Between these rocks the valley of ice stretches several leagues in length, and is nearly a mile broad; extending on one side towards Mont Blanc, and, on the other, towards the plain of Chamouny.

[Carl

Hackert, "Vue de la Mer de Glace et de l'Hôpital de Blair" (1781).

[Carl

Hackert, "Vue de la Mer de Glace et de l'Hôpital de Blair" (1781).

(Centre d'iconographie genevois)]

After we had sufficiently refreshed ourselves, we prepared for our adventure across the ice. We had each of us a long pole spiked with iron; and, in order to secure us as much as possible from slipping, the guides fastened to [290] our shoes crampons, consisting of a small bar of iron, to which are fixed four small spikes of the same metal. The difficulty of crossing these valleys of ice, arises from the immense chasms. They are produced by several causes; but more particularly by the continual melting of the interior surface: this frequently occasions a sinking of the ice; and under such circumstances, the whole mass is suddenly rent asunder in that particular place with a most violent explosion. We rolled down large stones into several of them; and the great length of time before they reached the bottom, gave us some conception of their depth: our guides assured us, that in some places they are five hundred feet deep. I can no otherwise convey to you an image of this immense body of ice, consisting of continued irregular ridges and deep chasms, than by resembling it to a raging sea, that had been instantaneously frozen in the midst of a violent storm.

[291] We began our walk with great slowness and deliberation, but we gradually gained more courage and confidence as we advanced; and we soon found that we could safely pass along those parts, where the ascent and descent were not very considerable, much faster even than when walking at the rate of our common pace: in other parts we leaped over the clefts, and slid down the steeper descents as well as we could. In one place, where we descended and stepped across an opening upon a narrow ridge of ice scarce three inches broad; we were obliged to tread with peculiar caution: for, on each side were chasms of a great depth. We walked some paces sideways along this ridge; stept across the chasm into a little hollow, which the guides made on purpose for our feet; and got up an ascent by means of small holes which we made with the spikes of our poles. All this sounds terrible; but at the time we [292] had none of us the least apprehensions of danger, as the guides were exceedingly careful, and took excellent precautions. . . .

We were now almost arrived at the other extremity, when we were stopped by a chasm so broad, that there was no possibility of passing it; and we were [293] obliged to make a circuit of above a quarter of a mile, in order to get round this vast opening. This will give you some idea of the difficulty attending excursions over some of these glaciers: and our guides informed us, that when they hunt the chamois and the marmottes, in these desolate regions; these unavoidable circuits generally carry them six or seven miles about, when they would have only two miles to go if they could proceed in a straight line. A storm threatening us every moment, we were obliged to hasten off the glacier as fast as possible: for, rain renders the ice exceedingly slippery; and in case of a fog (which generally accompanies a storm in these upper regions) our situation would have been extremely dangerous. And indeed we had no time to lose; for the tempest began just as we had quitted the ice; and soon became very violent, attended with frequent flashes of lightning, and loud peals of thunder, which being re-echoed within [294] the hollows of the mountains, added greatly to the awful sublimity of the scene.

We now descended a very steep precipice, and for some way were obliged to crawl upon our hands and feet down a bare rock; the storm at the same time roaring over us, and rendering the rock extremely slippery: we were by this time quite wet through, but we got to the bottom however without much hurt. . . .

[295] I cannot conceive any subject in natural history more curious than the formation and progress of these glaciers, running far into fields of corn and rich pasture; and lying, without being melted, in a situation where the sun has power sufficient to ripen the fruits of the field: it is literally true, that with one hand we could touch ice, and with the other ripe corn.

Williams at the Rheinwald Glacier

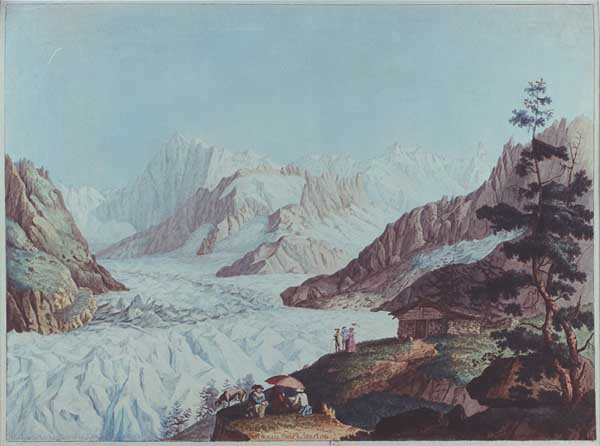

[Vol. II, 4] The ascent to the Glaciers on the opposite side of the valley appeared so romantic, that we regretted for a moment that we had not taken a route, which seemed not only pleasanter, but shorter; our mountain companions, however, silenced our murmurs by assuring us that every step we took, though apparently leading us further from the opposite mountain, would at length bring us nearer. We had been so often deceived in our ideas of distances in the Alps, which it requires long usage and a mountain-eye to calculate accurately, that we gave up our reason to the care of these [5] Grisons, persuaded that some mountain miracle would be wrought in our favour.

The latter part of our journey was extreme toil; at some distance from the top, the mule which had hitherto carried me was left tied to a rock, and our guides supported me up the rugged steep; my fellow travellers, who were furnished with crampons, little machines buckled to the feet, with points to enable the wearer to keep his hold, purchased their security by excessive fatigue from wearing them.

We were frequently overcome by the extreme heat, as well as by the difficulty of the path, and often stopped to cool our fever at the torrent which we saw bursting above, from its icy source. No inconvenience, we were told, resulted from taking this cooling draught; though far from being convinced of the truth of this [6] assertion, we were glad to find an excuse in the example of our Grisons companions, for quaffing this delicious beverage; and, like our first parent, "when not deceiv'd, but fondly overcome," he tasted, "of that fair, enticing fruit" [Paradise Lost, IX.996-8), so we, against our better knowledge, scrupled not to drink large libations of this tempting nectarious water.

With an inexpressible sensation of fatigue like the giddiness of delirium, breathless, and burning with heat, we threw ourselves, some time after mid-day, on the grass, along the icy boundary, from whose base rushed the torrent whence we gathered the icicles that again slackened our excessive thirst. These feelings of parched heat were not the effects of fatigue; we had taken as violent exercise beneath the hot noontide rays in the Italian vallies, with less [7] feverish sensations than we now experienced in those regions of winter. After a slight interval of repose, however, we found ourselves restored to that feeling of serene, tranquil delight, for which the philosophers who have written on the theory of the Higher Alps, account, from the purity of the atmosphere at that immense elevation; and which state of soothing happiness Rousseau has described with his usual eloquence, in a letter to Julia.*

[Louis

Bleuler, Rheinwald Glacier, c. 1826 (Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen)]

[Louis

Bleuler, Rheinwald Glacier, c. 1826 (Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen)]

[8] While my fellow travellers amused themselves by wandering over that world of ice, a difficult and dangerous enterprise, I sat down on the border of the Glacier, to enjoy the new and magnificent vision around me. On the right, rocks and mountains of ice, arose in dread and sublime perspective; before me, St. Bernadin lifted its barren and uncovered top; and nearly in the same direction, the eye wanders over a chain of Glaciers which separates the valley of the Rhine from the subject countries of the Grisons, Bormeo, and the Valteline. These were the Glaciers which, mid-way, we regretted not having scaled, and which our guides told us we should reacher sooner [9] in the direction we had already taken. So far as we might trust to the testimony of our senses, they were not mistaken. These Glaciers appeared to touch that on which we were now placed; and it seemed as if we had only to descend a little from our present elevation, in order to climb the savage and naked pyramids of rocks which raised themselves up from the far-spread desert of ice, like barren islands from a troubled sea. We were, however, separated from those objects by a space of several miles, measured on the ground; but the intervening gulph was hid from our sight by the swell of the mountains. On the left, the eye was borne over the amphitheatre of hills, green with pasturage, up to the ridge of ice, stretching along its own sullen, and perhaps incroaching boundary. The cattle were cropping the herbage on the steep, and the chamois bounding over the rocks, [10] for such the Grison-peasant told me were a few playful animals I perceived at the edge of the Glacier, over which my fellow-travellers were wandering. I employed the hours of meditation in throwing together the new images with which the Alpine scenery had filled my mind, into the form of an hymn, to the author of nature; and no spot can surely be more congenial to devotional feelings, than that theatre where the divinity has displayed the most stupendous of his earthly works.

The lengthening shadow of the icy-wall at the foot of which I was sitting, drew me from my meditations, and I began to be seriously alarmed at the absence of my friends. The opposite Glaciers were now lighted up with that glowing rose-coloured hue, with [11] which they are tinged at parting day. I gazed with rapture on this glorious vision, which I had before seen at an immense distance, and with feeble impressions compared to the enthusiastic, the solemn emotion I now experienced. The clouds were rolling high above the valley, but remotely beneath the spot where I stood, in gorgeously coloured billows, as their upper surfaces were tinged by the last rays of the sun.

While I was contemplating these majestic images, my fellow-travellers hailed us from a distant part of the mountain, to which they had descended from the Glacier. There was no time left to listen to their

Travels history,

Of Anters vast, and deserts idle,

Rough quarries, rocks, and hills, whose heads touch heaven,

[Othello, I.iii.139-141]

[12] all which I should have been very seriously inclined to hear, if our guides had not reminded us, that though the tops of the mountains where we stood were still rejoicing in the light of day, darkness already brooded over the face of the vallies.

The vapours gathered thicker as the evening advanced; and from the brow of the first slope where we descended, we paused a moment to snatch a nearer view of the tumultuous swelling tide of clouds into which we were about to plunge, rolling in silent but awful discordance along the valley, between the majestic streights of the Glaciers.

We had scarcely gained the spot where we left our mule, before the sun had taken his last leave of the pointed rocks on the opposite Glacier, [13] and night seemed rising from the valley. We found the bridle in the place where we had tied it to the rock, but the mule, in whose reputation for patience we had placed too much confidence, or who had formed a better judgment of the fit hour of retreat than ourselves, had withdrawn his head, and absconded. I had rather been borne, than supported to this spot, between two of our guides; a mode of conveyance which was both disagreeable and inconvenient. To walk down to the valley was for me impossible, to look for the mule along the mountains would have been a vain attempt, and to have sought another from below, would have delayed our return 'till midnight. In this perplexity, one of our Grisons-guides, who had rambled a few paces in search of the animal, returned with his arms full of shrubs, which he placed in two [14] leathern girdles fastened to the long poles that are the walking sticks of the Glaciers, and tied them together, so as to form a sort of chair, or litter; on this I placed myself, not without some apprehension, but was carried in perfect safety down to the cottage where we had breakfasted in the morning, and where we found our mule, who had been caught marching homewards early in the evening, and detained by the cottagers till our return.

The hours till midnight were filled up by my fellow-travellers, with accounts of their wonderful visions. I made a number of notes of what I had myself seen, and heard of the Glaciers; but after reading the glowing description given of those stupendous phænomena, by Mr. Ramond, in his elegant translation of Mr. Coxe's first [15] edition of his travels, I determined, instead of presumptuously intruding my own imperfect observations, or intelligence, to seize this occasion of introducing that finished essay to the English reader.

[Footnote, p. 7] The general impression felt by those who scale the higher mountains, where the air is pure and subtile, is a greater easiness in breathing, more lightness in the body, and more serenity in the mind. -- Meditation assumes, in those regions, something of a character great, and sublime, proportioned to the objects which strike us; something of tranquil rapture, remote from all that is selfish, or sensual. It seems as if, while raised above the haunts of men, we leave below all mean and earthly sentiments, and that, as we approach the etherial regions, the soul contracts something of their unchangeable purity. Upon the whole, this spectacle has something in it of magic and supernatural, which overwhelms the mind and senses; we forget every thing, we forget ourselves, and have scarcely a consciousness of existence.