German settlement in Central and Eastern EuropeSince the 11th century, German craftsmen, farmers, merchants, and others left their homeland to seek a better future for themselves in other parts of Europe and, alas, in the rest of the world. They emigrated because of poor economic, social, and political conditions, because of political and religious persecution, and because of scarcity of land. Sometimes they were called in by foreign rulers to help develop their own lands and were given enticements and privileges; sometimes they were resettled by their own rulers. The Germans from Russia were only one large group of emigrants who had settled in East Central and Eastern Europe. Very roughly speaking, Germans settled, or had been settled, in smaller or larger numbers and with interruptions in:

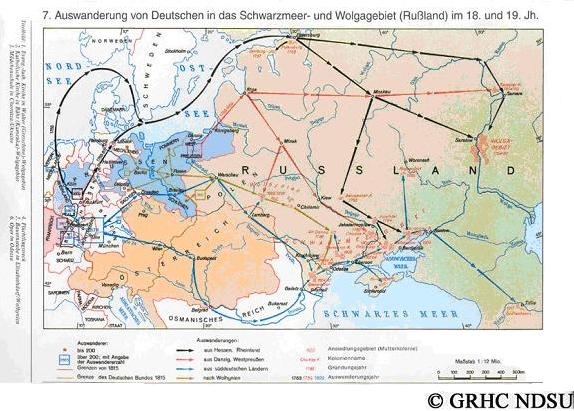

This list is by means complete.  Herbert Wiens, in his "A People on the Move: Germans in Russia and in the Former Soviet Union: 1763 - 1997, describes the regions from where the settlers came and where they settled, and their religious affiliation: Areas of originThe three main areas of emigration of the German Russians were Danzig-West Prussia, Poland, and the German province of Hesse. Many Mennonites came from Danzig (1789-1804) in addition to many Catholics and Evangelicals (1832). From Poland came those Germans who had previously emigrated there from Prussia and Württemberg; between 1815 and 1818 they left Poland and proceeded to settle in Bessarabia. The main emigration from Hesse left for the Volga between 1763-176. In the beginning of the 19th century, Germans also migrated into the Black Sea area, however, these emigrants came mainly from southwestern and southern German provinces of Württemberg, Baden, the Palatinate, Alsace, Rhine-Hesse and the area of Bavarian Swabia contiguous to Württemberg. Settlement areas in RussiaBetween 1763 and 1768, approximately 8,000 families totaling 27,000 people immigrated into the Volga region. Here, on the hilly side (right bank of the Volga) 45 colonies were founded, and on the meadow side (left bank of the Volga) 59 colonies were founded. The settlements were laid out strictly along religious lines.

The Volga Germans were mainly of Hessian descent, but many also came from the Palatinate and from Württemberg. The rural settlements near St. Petersburg and Belowesh (northeast of Kiev) and Rebendorf were founded at almost the same time as the German settlements on the Volga. The Volhynian Germans were for the most part Low Germans from the area of the Weichsel River and from Pomerania, Middle Germans from Silesia and Poland and High Germans (Swabians) from central Poland. By descent, therefore, the Volhynian Germans are northern Germans, by religion, Protestant.

Whereas the Volga and Black Sea-Germans settled in large closed villages, the Volhynian-Germans had to a large extent been settled in scattered settlements and on individual farms, which made community life more difficult. The first group of any size that settled in the Black Sea region was comprised of Mennonites from the Danzig area, who because of improved conditions for settlement established themselves south of Jekaterinoslaw (Dnjepropetrowsk) in 1789. The well-known region of Chortitza developed in this area. In 1803, the Mennonites, some from Chortitza, and some from the regions of Danzig and Elbing, settled in Tauria in the immediate vicinity of the small river Molotschna. The largest Mennonite group was created here in the Halbstädter or Molotschna territory. On February 20, 1804, by pursuant to a decree by Alexander I, a stringent selection process was applied to recruiting prospective emigrants from Germany. Emigrants were required to prove that they had adequate resources to support their livelihood. This recruiting process was particularly successful in the provinces in southern and southwestern Germany. In the provinces of Cherson, Bessarabia, Jekaterinoslaw, Crimea, and South Caucusus (1817) very large closed settlement areas were founded on allotted lands. Denominationally, the Germans in the Black Sea area were divided as follows:

In addition, there were German settlements in the Caucasus like those later founded south of the Urals and in western Siberia. Resettlement of the ethnic Germans by the Third ReichAt the end of the First World War, 1,5 million Germans lived in the Soviet Union, 1.2 million in Poland, 3.5 million in Czechoslovakia, 120,000 in Lithuania, 550,000 in Hungary, 800,000 in Rumania, 700,000 in Yugoslavia, 70,000 in Latvia, and 30,000 in Estonia. But Germany's interest in these 8,5 million Germans really only began under the National Socialists who wanted to bring these Volksdeutsche [1], as they were called, "Heim ins Reich." They did so by brutally expelling the local population on the eastern borders of the Reich—sometimes only with a few hours' notice—and replacing them with Germans, thus attempting to ensure Germanization of the region. The long-range aim of the Reich was the establishment of a uniformly German settlement region west of a line extending from the Crimea to Leningrad. The Slavic population—where not "needed" as slave labor—was to be transplanted along the Ural Mountains. The Volksdeutsche rarely had German citizenship and—considering the lack of contact that they had with a German state over the centuries—did not have Reich sympathies, at least initially. They were "repatriated" on the basis of agreements with the countries concerned, finally also with the Soviet Union, in exchange for relinquishing claims to the areas from which the Germans were to be resettled. At first, the relocation was carried out in a relatively humanitarian manner for the Germans concerned. But as time went on, the Germans were forced to emigrate. Between 1940 and 1944, 166,000 Germans from Poland, 127,000 from the Baltic countries, 370,000 from the Soviet Union, 212,000 from Rumania and 35,000 from Yugoslavia were resettled into newly acquired regions (esp. the so-called Warthegau), the Generalgouvernement, or the Altreich. The Warthegau was established soon after Germany's attack on Poland. It consisted of the former Prussian province of Posen and parts of Poland. 85% of the population was Polish, eight percent were Jews and seven percent were Germans. Already in 1939 plans had been made as part of the Nazi population and Lebensraum policies to expel hundreds of thousands of "persons of inferior race" from the their farms and homes to this region.  Source: http://motlc.wiesenthal.com/resources/books/genocide/chap04.html This is not the place to describe the events occurring towards the end of the War as the Red Army advanced. The numbers speak for themselves: 16.6 million Germans lived in the East at the end of the war: 9.58 million in the Oder-Neisse region, 3.48 million in Czechoslovakia, 250,000 in the Baltic countries, 380,000 in Danzig, 1.37 million in Poland, 623,000 in Hungary, 537,000 in Yugoslavia, and 786.000 in Rumania. Within a few months after the end of the War, 11.7 million fled, or were expelled, and arrived in the West. At least 2.1 million died. 2.65 million remained in their homeland. Canadian immigration regulations for Germans after World War IIAlthough Canada did not admit German nationals between 1939 and 1950, some 30,000 persons of German origin were, in fact, permitted to immigrate between 1947 (no immigrants at all were admitted to Canada between 1945 and 1947) and 1950 when all restrictions were lifted and Germans were included among the Canadian government's preferred immigrants. In May 1947, Canada's new immigration policy provided for the resettlement of displaced and homeless persons from Europe. Volksdeutsche refugees who were not German nationals were included from the beginning in this new policy, which enabled 21,000 of them to enter by September 1950. The Canadian Christian Council for the Resettlement of Refugees—which was founded in 1947 with the support of the Canadian government by representatives of the Canadian Lutheran, Catholic, Mennonite and Baptist Churches, and the Sudeten Germans—prepared eligible prospective German immigrants for presentation to the Canadian government screening teams in Europe. By 1950 it had arranged the immigration of 15,000 German-speaking immigrants, and by 1953 a total of 30,000, in spite of huge financial problems. Only a monthly grant of $10,000 from the Canadian government and the refitting and chartering of the SS Beaverbrae with a carrying capacity of almost 800 people could the CCCRR function adequately. Canadian authorities were also sympathetic to Canadian Russlaender Mennonites' requests to bring in Volksdeutsche as early as 1947. The Mennonites were able to convince the Canadians that the Mennonites had not left the Ukraine voluntarily, that they were not Volksdeutsche but were of Dutch origin, and that they had not served in the German army or any branch of the Nazi party. By September 1950, 6,500 Mennonites were moved to Canada from Germany. Meanwhile, German-Canadians who were willing to sponsor friends and relatives were deeply resentful of the fact that Canadian immigration discriminated against uprooted Germans while nationals of most other countries were admitted from 1947 on. A growing lobby including the CCCRR, the Mennonite Central Committee, the German-language press in Canada, and the resurging German-Canadian associations, as well as several departments of the government, pressured for selective exemptions from the enemy alien prohibition. As a result, in addition to the 21,500 Volksdeutsche, almost 4,000 natives of Germany and 5,000 persons of German origin from other countries were able to enter Canada between 1945 and 1950. At first, the only categories exempted from the prohibition were children under 18, wives and proven opponents of the Nazi regime. Then German war brides of Canadian veterans and residents of Danzig prior to 1939 became eligible. In 1949, German nationals who were parents or dependent children of Canadians became admissible. Then German businessmen and students were permitted to enter on visits. During 1949 government officials became aware that 90% of the Volksdeutsche who had entered Canada since 1947 had assumed German citizenship during the Third Reich. In 1950, therefore, even those Volksdeutsche and close relatives of Canadians who had accepted German citizenship after September 1939 were declared admissible. After the removal of all restrictions, ethnic German immigration jumped from 5,800 in 1950 to 32,400 in 1951 when Canadian immigrants were the largest ethnic groups and exceeded those of British origin by 1,000. German immigration peaked in 1953 with 39,000 and then declined again to 12,000 by 1960. A high proportion of the immigrants listed as "German" by ethnic origin were refugees. However, Canadian statistical data about German immigration did not distinguish between natives of West Germany and displaced persons from the East, such as refugees from the Soviet Zone of Germany, expellees driven from those parts of Germany annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union after the war, and Volksdeutsche who had fled from their east European homelands to West Germany. [2] Notes[1] Volksdeutsche refers

to Germans who lived outside the eastern boundaries of the German Reich;

Reichsdeutsche to Germans living within the boundaries of the German Reich before 1938.

|