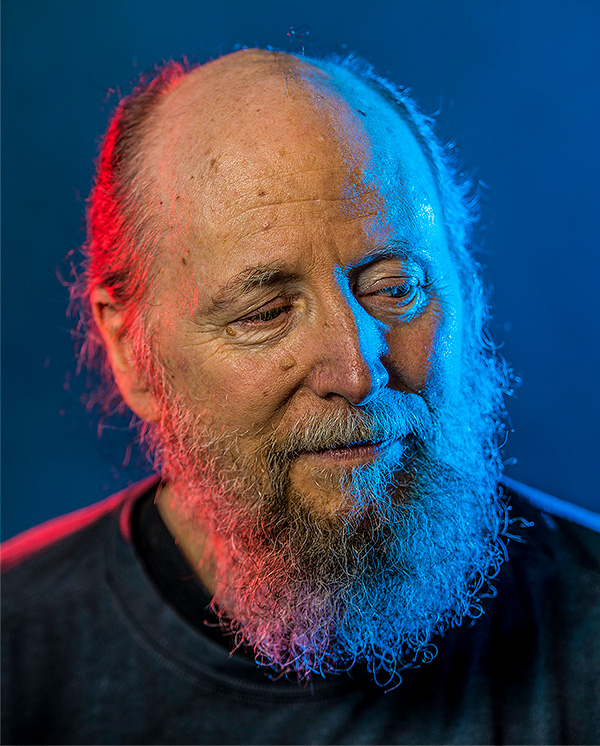

Photos by John Ulan

As an author, he stands among the one-name heroes of Canadian literature: Atwood, Munro, Wiebe. At the helm of the U of A creative writing program for many years, Wiebe's "writing is hard" outlook and wry sense of humour helped forge successful authors and stoke a passion for language. So when a former student set out to profile this iconic writer and editor, it seemed only natural that we invite him to have the last word.*

*Editor's note: While all comments and edits you see here belong to Rudy Wiebe, the handwriting does not.

For the past 20 years, Wiebe has done his writing in his book-lined home office. His collection, which has begun to outgrow his shelf space, includes books on Arctic, Mennonite and western Canadian history.

There is a small, narrow seminar room on the fourth floor of the Humanities Building with windows that overlook the North Saskatchewan River Valley, the High Level Bridge and the downtown Edmonton skyline. The view aside, there's nothing really remarkable about the room, but it's my favourite spot on campus. It was here that a gruff, sometimes cranky professor helped an unfocused and indifferent student uncover his true vocation.

I met Rudy Wiebe, '56 BA, '60 MA, '09 DLitt (Honorary), in the summer of 1979. A zoology major who didn't really want to study science anymore, I had found his introductory creative writing class while flipping through the thick U of A calendar for half-interesting electives to round out my final year. The prerequisites for admission included a portfolio, so I wrote a couple of short stories and slipped them under Wiebe's door in the mostly deserted Humanities Building in late August. When Wiebe summoned me a few days later, he made it quite clear the samples I'd provided were execrable. Then he told me I could go ahead and register because in one of the stories, based on real events, I'd at least tried to write something I had a clue about: being young and stupid.

I was no standout in that first class, but evidently I did well enough to earn entry to Wiebe's intermediate course in the winter term. By its end, I was hooked on the process and challenge of storytelling and had abandoned any remaining thoughts of a career in biology. One way or another, I have made most of my living through writing ever since.

Over the years, Wiebe and I have stayed in touch, our relationship slowly evolving from one of teacher and student to a friendship. It is centred on coffee and conversation every few months in a Second Cup several blocks from Wiebe's home in the Old Strathcona area of Edmonton. Winter or summer, he always walks to our meetings: a man in his 80s still ramrod straight, fiercely engaged with life and arriving with a head full of big ideas to discuss.

We are friends now but he still intimidates me. Part of it is his talent and output. Wiebe is one of the finest writers this country has ever produced. His craggy face, grey-white beard and piercing gaze are well-known to CanLit readers. Beginning with his novel Peace Shall Destroy Many in 1962, he has published more than 25 books - including 10 novels and five short story collections - and edited or contributed to many others. His accolades include two Governor General's Awards for English-language fiction.

While Wiebe's themes are many and varied, the principal subjects of his writing are the Mennonite diaspora and the experience of Canada's Aboriginal Peoples under white domination.

Through deeply researched novels he has explored the First Nations perspective on white exploration, commercial expansion and settlement in Canada with boldness, honesty, complexity and respect. The origins of his interest come from childhood. "I remember when I was a kid growing up and going to school, I was living on a homestead in northern Saskatchewan with reserves on either side of me. We saw Native people driving by with their ragged horses going to Turtle Lake to fish, and sometimes we bought fish from them, but the history we got in school was the Longfellow 19th-century romantic Indian brave and his squaw kind of crap. Completely ludicrous," he says.

Wiebe has also written ambitious historical fiction about the Mennonites in Canada and their experience of leaving eastern Europe in search of freer, safer lives. His parents were Mennonite immigrants who fled religious persecution under the Stalinist regime in the former Soviet Union in 1930. They homesteaded in the school district of Speedwell, Sask., where Wiebe was born in 1934, before moving to Coaldale, Alta., in junior high school. His memoir, Of This Earth: A Mennonite Boyhood in the Boreal Forest, explores his childhood experiences.

He is grateful for what this country gave his family and, because of that, has little patience for those who are critical of Canada taking in thousands of refugees from countries like Syria, upended by turmoil. "Since so many of us here have come from elsewhere within two or three generations, we, of all people, should be able to understand and accept others in similar situations," he says. "A wealthy middle power like Canada could be doing more."

I confess here I had read none of Wiebe's work when I signed up for that first class with him in 1979, but I slowly caught up and have now read most of his books. Getting through one of his novels requires concentration; he has an idiosyncratic attitude toward punctuation, and his syntax can be a challenge to follow. His entry in the Canadian Encyclopedia says this of his style: "though sometimes ungainly, [it] frequently results in an eloquence that is both appropriate and evocative." To put it another way, he is a writer who expects his readers to do some work, but that work is richly rewarded.

Wiebe could obviously write simpler, more straightforward stories, but he rejects the easy approach to his art. "Writing is hard, so there is no point being half-assed about it," he says.

For me, that uncompromising attitude is evident in his decision in the novel A Discovery of Strangers to take on a multi-layered story about Sir John Franklin's little-known first expedition overland through the Coppermine River region and his fateful contact with the Dene people. He could have easily, instead, written about the infamous third expedition, in which the explorer and 134 men on two Royal Navy ships disappeared in the Canadian Arctic while searching for the Northwest Passage. A novel about the lost expedition might have attracted more readers but it held no appeal for the author. "I didn't find anything particularly interesting about the idea of a bunch of Englishmen on two ships slowly discovering they are going to die," he says. "We already know the what, but the why is always the more interesting part of a story for me."

Wiebe brought that tough-mindedness about good stories and the storytelling craft to his role as professor. He taught other courses during a 25-year career in the U of A English department, from 1967 to 1992, but spent most of it leading intense and demanding creative writing classes based on the approach he learned as a grad student at the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop at the University of Iowa. Wiebe, now professor emeritus in the Department of English and Film Studies, was one of the first teachers in Canada to employ the workshop technique that is, these days, pretty much universally practised in creative writing programs.

Detailed, no-holds-barred vivisection of student work was the main instructional mode in his classes. Perceived laziness on the part of an aspiring writer was something approaching mortal sin. Tom Wharton, author of highly regarded novels such as Icefields and Salamander, studied with Wiebe and now teaches creative writing at the U of A, one of Wiebe's successors in the job. Wharton remembers with a rueful laugh that one of the most damning things Wiebe could write in the margins of a draft story submitted to his workshop was a single word, scribbled in response to a sentence or passage he found wanting: "feeble." I remember seeing that cringe-inducing feedback on my work, too.

"Rudy was the kind of teacher you came to appreciate much later," Wharton says, dryly. He remembers retreating to the campus pub more than once with classmates after a workshop "to drink and badmouth" their professor. "But 90 per cent of the time, he was right," Wharton says now.

Suzette Mayr is an associate professor of English at the University of Calgary and the author of several novels including Moon Honey, The Widows and Monoceros. With Wharton, she was part of Wiebe's final graduate-level writing workshop at the U of A in 1991-92. Mayr says: "He had a really hearty respect for research and for doing your due diligence as a writer." With a laugh, she recalls one session in particular. "Rudy bawled us all out about something Tom had written about the Cretaceous era. He said: 'Do any of you even know what the Cretaceous was?' "

Mayr says she would never undertake the kind of sprawling historical fiction that Wiebe has written but appreciates his view on research: "There is a library of books to read before you start your own book." As a writer who teaches, she also admires his dedication to maintaining a writing practice. "Rudy once told me that he actually took a decrease in pay and course load to keep writing."

Aritha van Herk, professor of English at the U of C and author of five novels and several books of non-fiction, was also a student. "Rudy could be impatient and difficult, and he didn't suffer fools gladly," she remembers. "At the same time, he was generous with his attention and, as a teacher, mostly interested in the quality of the writing. Although he had strong opinions, he didn't indulge in the ego trips of some writing instructors who expect students to be their clones or sycophants."

Van Herk battled with Wiebe many times, particularly as a master's student working under his supervision on her first novel, Judith, yet she holds a high regard for the man, his work and his teaching. "Rudy's strengths as a teacher were his attention to detail and his awareness that we should be writing our own stories about Alberta, based on our experience and the world we know."

While Wharton, van Herk and others worked quite successfully with Wiebe, being his student was not a positive experience for everyone, even in hindsight. One former student who has since gone on to publish a couple of well-reviewed novels responded to my request for an interview in a terse email message: "I don't think I'm the right person to talk to."

Wiebe knows he was famously hard to please and admits to some regrets. "At a certain point, you have to become a kind of judge, you know. And maybe I shouldn't have been as judgmental as I was, but that was my way of approaching things. This is good, this is poor, this is just plain shit. But sometimes," he concedes, "you may miss some really good stuff."

Wiebe acknowledges he is not an easy man to get close to, but those who have earned his trust discover a very loyal friend. His best friend in the literary world was the late novelist and poet Robert Kroetsch, whose death in 2011 at age 83 after a car accident was a body blow to Wiebe. He is a tough man but I saw him in tears the afternoon he delivered a eulogy at Kroetsch's funeral. "They were night and day as personalities, but they had a real shared interest in the West and in literature," van Herk says of the writers' close bond.

Another important, if very different, literary friendship is with Yvonne Johnson, the woman with whom Wiebe co-wrote Stolen Life: The Journey of a Cree Woman. Johnson, the great-great-granddaughter of Big Bear, read Wiebe's richly layered novel, The Temptations of Big Bear, about the Plains Cree chief unjustly implicated in the 1885 Frog Lake Massacre, when she was in Kingston Penitentiary serving a life sentence for murder. (She, who had suffered years of physical and sexual abuse as a child, was part of a drunken group convicted of the beating death in Wetaskiwin, Alta., of a man they believed to be a child molester.) Johnson wrote a letter to Wiebe asking him how he knew so much about her famous ancestor, and they began to correspond. Eventually, they met at the prison and Wiebe helped Johnson tell her poignant and harrowing life story in the book. He also testified on her behalf at parole hearings over the years. Now out of prison and living in southern Alberta, Johnson says: "I love Rudy to pieces. He has always been very respectful, kind and gentle with me."

I was given a glimpse of how seriously Wiebe takes the responsibility of friendship while working on this profile. Late last fall, he got word that Gil Cardinal, the writer and director with whom he collaborated on the screenplay for Big Bear, the 1998 CBC television miniseries adapted from The Temptations of Big Bear, was in an Edmonton hospital. Though the two men hadn't spoken in quite some time, Wiebe immediately went to visit Cardinal in hopes of buoying his spirits. He got as much out of the visit as Cardinal did. "Gil had the same sharp wit I remembered, even though his body was completely ruined," Wiebe said. A few weeks later, shortly before Cardinal succumbed to his illness, I joined Wiebe at a luncheon where members of the Alberta film and television community honoured the Métis filmmaker with the 2015 David Billington Award for his impressive life's work. Cardinal was by then too sick to attend, but for Wiebe it was important to go and pay tribute. Throughout the afternoon, I watched as he sought out many of Cardinal's other friends in the room to share a story or a memory about the man.

In contrast to his legendary ferocity as writer, teacher and activist, the personal Rudy Wiebe is quiet and private. He and his wife, Tena, who have been married for 58 years, spend much time with their two children, four grandchildren and their church community. But family life has also been a source of great pain for Wiebe. His last novel, Come Back, was published in the fall of 2014, around the time of the author's 80th birthday. A long time surfacing, it is the story of a retired professor's attempt to understand his son's decision to take his own life years earlier.

The novel was inspired by the loss of Wiebe's eldest son, Michael, to suicide in 1985. He was 24. When I asked Wiebe about writing the most difficult book of his career, he began to answer by telling me he'd once heard American novelist John Irving declare that he always writes the last sentence of his books first so he knows where he's going. "I did not know where this novel could go, but I knew where it began," Wiebe said. "For a long time, I had never thought of writing a story like that. But at a certain point, when you get a certain distance from it, it tends to grow." He knew the subject matter was not his exclusively, however. "I talked it over with my family. They said, 'Are you sure you want to do this?' but they didn't hesitate at all."

Julienne Isaacs wrote of the novel in the Globe and Mail: "There is no cure for the pain of premature loss. Longing for the missing loved one will tug at the heart, call that command in perpetuity. Wiebe makes us attend to the beauty of the call." Possibly even more important to Wiebe than the formal reviews, however, are the informal ones received from others who have endured a similar loss. "It's not a particularly easy book to read, in one sense, because it tries to grapple with that sense of not feeling adequate, or 'What's wrong with me?' " Wiebe said. "But many, many people have thanked me for writing it."

Writing Come Back was an act of bravery. Necessary, and hopefully healing, for Wiebe, but brave. In writing the novel, Wiebe exposed himself in ways that he has never been comfortable doing. Then again, Wiebe has never lacked for courage, especially the courage of his convictions. He has written complex books - difficult to write, challenging to read - because that's the way he believes those stories had to be told. He chose being a demanding teacher over a popular one because he felt that doing otherwise would not be doing his job. And through his activism, he has stood up for individuals in trouble when others have abandoned them, like Yvonne Johnson, because of his belief that everyone deserves a chance to reclaim their lives.

One sunny afternoon last September, Wiebe and I took a walk around North Campus. "Look at all the bright young faces," Wiebe said, watching nervous-looking undergrads rush past on the way to class. He pointed to St. Stephen's College, his first residence when he arrived here as a 19-year-old in the early '50s. Later, as we passed the Old Arts Building, he told me a story about legendary writer W.O. Mitchell, who sometimes came up from Calgary to cover Wiebe's workshop. Mitchell used to collect and read student work aloud in class instead of having the students read and analyze it for themselves beforehand. Wiebe wasn't a fan of this approach. "Mitchell was such a good reader - he was an actor, really - that he could make anything sound good, including stuff that probably wasn't," Wiebe recalled with a laugh.

Entering HUB Mall, we passed the coffee stop formerly known as Java Jive. My turn to remember: midway through Wiebe's three-hour workshops, many of us came here to refuel with caffeine, not infrequently nursing the wounds of a stinging critique. Not that it always hurt; Wiebe's stern countenance belies an offbeat sense of humour and I remember plenty of laughter in his workshop, too.

Eventually, Wiebe and I arrived at the last stop of our tour, making our way up to 4-59, the creative writing seminar room in the Humanities Building. Neither of us had been back for a long time. We spent a few moments just absorbing that breathtaking view of the river valley. We both noticed, with a mix of amusement and nostalgia, that although the furniture in the room had been replaced, the same framed Alex Colville print, Dog, Boy, and St. John River, still hung on one wall.

After assuming his usual spot at the head of the long table, Wiebe grew reflective. "We were the first class in here and I was the first teacher. The building had just been built and a room had to be assigned to the writing class, so I asked and they gave me this beautiful space," he said. "It's a very moving experience to sit here now and think of all the people who've worked in here. A lot of students, a lot of stories."

Looking across the table at Wiebe, I contemplated my own experience up here in a handful of undergraduate and graduate classes with him between 1979 and 1984 (a sweaty-palmed, heart-pounding experience whenever it was my turn to present a new piece to the workshop). He was not the warmest or most encouraging prof I had at the U of A, but somehow it was his teaching that had the most profound impact upon me. I have yet to achieve half of what I aspired to as a writer, but Wiebe made me want to reach for something more than mediocrity.

He still does. Now at an age when others might say that's enough and be content to sit back and rest (on the couch if not on their laurels), Wiebe continues to spend part of most days at his desk working. He recently finished the footnotes for a book of his collected essays to be published in fall 2016 by NeWest Press. And he is definitely writing something else, though he refused to say whether it's a new novel. "You know I never talk about what I'm writing," he scolded.

As a final question, I asked Wiebe what advice he might offer the next generation of writers, in an age dominated by 140-character tweets and other wafer-thin social media, of dying newspapers and magazines and what feels like the near-extinction of independent bookstores. But Wiebe is not worried about the future of literature or those who create it. He believes that for writers, the real ones, this is a calling, not a job, and they will find ways to keep writing - whatever form that takes.

"It seems to me that storytelling is a uniquely human gift that allows us to put visions in each other's heads, and that's not going to stop."

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.