It's no longer enough for undergraduate students to just attend classes and study hard. Students like Justin Selner pack a variety of interests and experiences into their undergraduate years.

Gone are the days when undergrads spent four years stuck in lecture halls. The 21st-century student publishes in journals, travels the globe and then does volunteer work at home. Meet the global citizens headed into the real world armed with so much more than a degree.

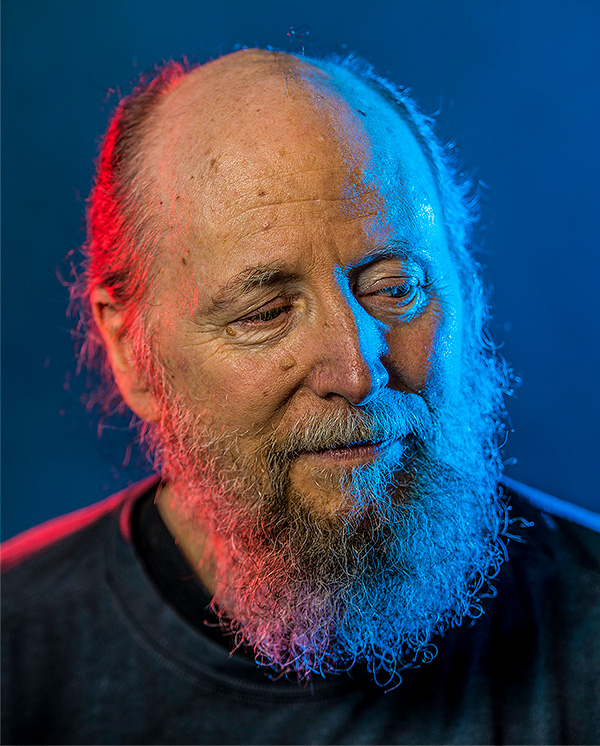

A week after tonsil surgery, 16-year-old Justin Selner was at home holding a bowl under his mouth to catch the blood. It was gushing, he was choking, and his mother, a recent nursing grad, was panicking. She drove him to a St. Albert hospital where, he recalls, "I'm getting an IV in both arms and a doctor and five nurses are working on me."

After the anesthetic wore off, he awoke in the back of an ambulance. "We're rushing you to the University hospital," said a paramedic.

The University of Alberta is where Selner was always headed, but not so soon and definitely not under these circumstances. A competitive swimmer who'd competed internationally and once dreamed of the Olympics, he was just months from becoming a Golden Bear varsity athlete. After losing four litres of blood and 14 kilograms, he spent the next year and a half recovering.

"My goals never changed," says Selner, who will graduate with a BA(Hons) this spring, "but my body changed. Mentally I was still committed, but the physical reality didn't match that." Stroke after stroke, he saw teammates' hands touch the wall before his. It would take him a year and a half to merely match his old lap times. "It was hard to watch."

Today, he's wrapping up an honours political science degree, but at the time he didn't even have a major. As he puts it, "I was the athlete-student, not the student-athlete." For Selner, an admitted overachiever, his education had to match the demands of his swimming, which would seem impossible for someone who was in the water more times a week than there are days. But through the U of A, he found a way to make his undergrad experience work at his pace.

Last summer alone, the student-led non-profit Golden Future sent him to South Africa to assist teachers with promoting health and post-secondary education, just before the U of A Go Abroad program set him up with an internship at The Protection Project, a D.C.-based think-tank on human trafficking. Then, after attending a UN conference on discrimination against women, he returned to Edmonton to finish his self-directed research on how the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) may offer growth opportunities across Africa, a project for which he received a $5,000 grant from the Undergraduate Research Initiative. In March, he received the Lou Hyndman Edmonton Glenora Award - $20,000 over two years - for outstanding leadership, high academic standing and involvement in university or community organizations. And somewhere in between he climbed Mount Kilimanjaro.

A generation ago, undergraduate students with a modicum of Selner's stamina would be left to search out their own opportunities. To research, travel abroad and intern in your field - before graduation - was almost unheard of. Now, as a result of the Students' Union and University's efforts, undergrads are graduating more confident and more experienced than ever.

Undergrad revolution

There has been a quiet proliferation of literature on campus and, though far from Marxist, it is changing the way students think about the redistribution of educational wealth.

From the anthropology department's Diversipede to PoliSci's The Agora, these undergrad research journals are written, published and peer-reviewed by students like Selner. There was no institutional effort behind them, says Crystal Snyder, '10 MSc, research co-ordinator for the Undergraduate Research Initiative. She's seen them simply crop up over the last few years.

The URI, however, took eight years of championing before its 2011 launch with a $200,000 investment. What started as a Students' Union idea got a little bit of help from the Office of the Dean of Students and CaPS U of A Career Centre, and now offers students grants to do research - not for grades, but in the pure pursuit of new knowledge. Each applicant just needs a quality proposal that is interdisciplinary and will contribute to the student's own knowledge and skills, plus a faculty supervisor. Sometimes, URI simply acts as matchmaker between undergraduates and professors looking for extra help on current research.

Andrea Budac used a $5,000 URI grant to help Dr. Sean Gouglas's team understand the attachment video game players have to their avatars, the user's graphical representation in the game. The URI stipend supported her last 12 months of coding and analyzing how players of the popular video game Mass Effect reacted to the introduction of the game's first heroine. Once completed, Budac, a computer science major set to graduate in 2014, hopes to see her name in a cultural studies journal and improve her chances of getting into a master's program. But she's already benefitting: "Getting the URI showed me research could be easier than I thought."

Snyder sees URI as more than a bridge to graduate school. "They're developing skills that are relevant to their discipline. They're meeting people. They're getting outside the classroom and seeing all the possibilities of what they can do with their degree," she says. "We're very focused on having students get the most out of their undergraduate experience."

Though URI is unique in Alberta, the experience-focused revolution in undergrad studies is happening across North America. Some trace the impetus to the 1998 Boyer Commission report by the former U.S. commissioner of education, which suggested undergraduate education was failing its baccalaureate students. Completed shortly after Ernest L. Boyer's death, Reinventing Undergraduate Education: A Blueprint for America's Research Universities, accused academia of caring more about credentials than experience, being too pedagogical and turning the freshman year into a "repetition of high school curriculum."

It was especially critical of research institutions, suggesting they had the habit of championing their professors while simultaneously refusing undergraduates access to them. "If those challenges are not met," the report read, "undergraduates can be denied the kind of education they have a right to expect at a research university, an education that, while providing the essential features of general education, also introduces them to inquiry-based learning."

Removing the barriers between baccalaureates and doctorates, Boyer believed, could only strengthen schools. Frank Robinson, vice-provost and dean of students, sees it that way, too. "We sometimes apologize that we are a research-intensive university," he says, "and I'm sick and tired of that because there are advantages for students being here. One of them is that students can actually stop just being passive learners - writing notes and memorizing for the exam - and begin generating knowledge."

If it wasn't for undergraduate research, Robinson doesn't think he'd have a degree, let alone a fifth-floor corner office on the campus of one of the world's top schools. As a young man at the University of Saskatchewan, he was ready to drop out by the third year of his studies until an animal science behaviour class changed his mind. "I spent the whole semester looking at chickens in cages, seeing whether they would avoid looking another chicken in the eyeball if they were a dominant or subordinate chicken." Not only did it get him his first A, but it led to his life's work: "I'm a chicken gynecologist by training."

As a professor he's not abandoning pure lecture-style learning, but he does emphasize research and hands-on experience to his first- and second-year students. One student, Josh Perryman, was not counting on the latter. The shy 19-year-old panicked when he learned about "There's a Heifer in Your Tank," the professor's popular course that turns research about agriculture into a theatrical performance before a public audience of 400.

"I spent the first class on my iPad … trying to find another class I could take instead," says Perryman. "But staying in the class was one of the best decisions I've made. Getting to do that research and making those contacts outside of university really helps get a feel for other paths that I could take in this field." (See the sidebar, "Say Goodbye to the Lecture Hall," for more on the class.)

Indeed, removing the uncertainty that haunts students from the day they enrol to the day they start the job hunt is a huge feat. From the moment they don their robes and shake hands with the university president, they're anxious to know whether the next hand they're shaking will be connected to a suit or a paper hat. And who could blame them? According to global management firm McKinsey & Company, only 45 per cent of employed university graduates felt adequately prepared for their careers. Sadly, even fewer employers thought the graduates came to them adequately prepared. The survey results are even stranger when you note that almost three-quarters of educators believed they were adequately preparing students. Have academics been living in their own bubble?

Moving toward exceptional

A linguistics graduate, Chelsey Nazar, '03 BA, has one word for her U of A baccalaureate experience: "unexceptional."

"It was nothing more than attending classes and passing exams," she says. "We never experienced anything first-hand." Nazar believes she could have done just as well by studying the textbooks and only showing up for mid-terms. Whether or not she's right, her opinion is echoed by thousands of Canadian graduates each year. But in the past decade, universities have started responding to their grievances.

Though untimely for Nazar, the same year she graduated the U of A launched the Community Service Learning program for students like her, who were seeking more first-hand experiences. The CSL matches students' coursework with volunteer work for credit, so the students, communities and non-profits all stand to benefit.

Pat Conrad is the executive director of SKILLS, a 30-year-old Edmonton-based non-profit that finds meaningful ways for disabled people to participate in their communities. When a colleague told Conrad about CSL in 2004, she jumped at the opportunities it offered. For more than 20 years, U of A students had completed practicums at SKILLS, but the Nonprofit Board Internship Program - offered by CaPs and CSL - was a chance to bring fresh minds to the group's elected body. Not only did they bring new knowledge to the board, but Conrad says they also helped hold it accountable. "We have really good ideas about things we want to do, but critical issues and other stuff get in the way, and we don't fulfil some of what we hoped we would," she says. "But the students' presence pushed us to stay on path with projects that were really meaningful."

From the students' perspective, Conrad says the real benefit isn't the credits they collect but seeing their textbooks come to life. New alumnus Jon Weller, '12 BA , agrees.

After interning for a community development organization in rural India, Weller graduated with a CSL certificate that shows future employers he's gained knowledge through both textbooks and community involvement. Now a filmmaker with a company that makes promotional films for non-profits, Weller says the experience helped him overcome his post-graduation anxieties. "It gave me a lot of confidence in just knowing that I can step into a role I haven't done before and I'll figure it out eventually."

Making global experience local

The push for international studies is even happening at the federal level. In 2011, a Foreign Affairs advisory committee released the report International Education: A Key Driver of Canada's Future Prosperity. It said that Canada should lead the charge for international education "in order to attract top talent and prepare our citizens for the global marketplace, thereby providing key building blocks for our future prosperity."

Recently hired as director of education abroad at U of A International, Kate Jennings has worked for similar programs at four major Canadian universities and has noticed their evolving mindsets. "What we're seeing more at universities, the U of A included, is making sure that [students'] learning abroad is being thoughtfully considered as part of the curriculum back home." Even though U of A International is 30 years old, it is now working to truly ensure that its programs reflect the "global context" of what students are studying.

Last year Arisha Seeras, '12 BSc(FoodSci), and other Faculty of ALES students spent a week in Cuernavaca, where they visited La Estacion, one of Mexico City's poorest regions. There, they helped repair houses where pocked walls were stuffed with newspapers and roofs were outfitted with loose aluminum sheets. It might seem unrelated to her nutrition studies, but she remembers the moment it clicked into place: "[In class] we discussed a lot about how the lack of money in your environment contributes to a poor diet, and it was after I visited La Estacion that I realized how much of that is true." Today, Seeras is a food scientist at Agri-Food Discovery Place, the University's bio-product processing facility, where she works to reduce the spread of listeria in deli meats.

U of A International has seen nursing students work in Ghanaian hospitals, engineering students intern with German firms and fine arts students learn at Italian satellite universities. With each return flight, Jennings hopes the students arrive home with higher doses of teamwork, and intercultural and communication abilities - all of the "soft skills" she says employers are looking for. She points to a QS World University Rankings survey of 10,000 employers in 116 countries. It showed that 60 per cent of them gave "extra credit" to candidates with international student experience, and 80 per cent actively sought students with international studies.

"Canada has realized we need to get our young students more engaged in the international environment," says Jennings. "Not only to keep Canada competitive, but also to make sure our graduates are getting the full experience of what a university education can be."

A learning community

With Canadian tuition costs rising an average of 350 per cent since 1990, it shouldn't surprise anyone that undergraduates want more from their universities. But many of these opportunities are actually funded through donations. Both the Undergraduate Research Initiative and Study Abroad Programs are supported by the university's Annual Fund, one of the school's largest funds and one of only two fundraising programs that funnel money university-wide.

With all of this emphasis on experience outside of the classroom, it leaves one wondering whether we're forgetting the hallmarks of academia: pure knowledge and critical thinking.

Campus Saint-Jean student Emerson Csorba doesn't want to see universities abandon discussion- and lecture-style education. "It forces students to communicate their thoughts effectively, consider others' points of view and defend their own arguments," says Csorba, a third-year arts student who co-founded TheWandererOnline.com. However, he does see a lot of potential in research- and experience-based learning. In fact, as former Students' Union vice-president, academic, he cut the ribbon that opened URI.

"As universities move toward more of a community-service approach to learning, where movement and hands-on learning are paramount, we should question whether our university classrooms fit within this experiential focus." He respects programs that remove the hierarchy created by desks pointed toward a professor at a table like a preacher at a pulpit.

Professor Robinson also wants this hierarchy erased. "I want to build a learning community - not a class," he says. "Anybody can get a class with a list from the registrar's office - that's a class. But I want to make a learning community."

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.