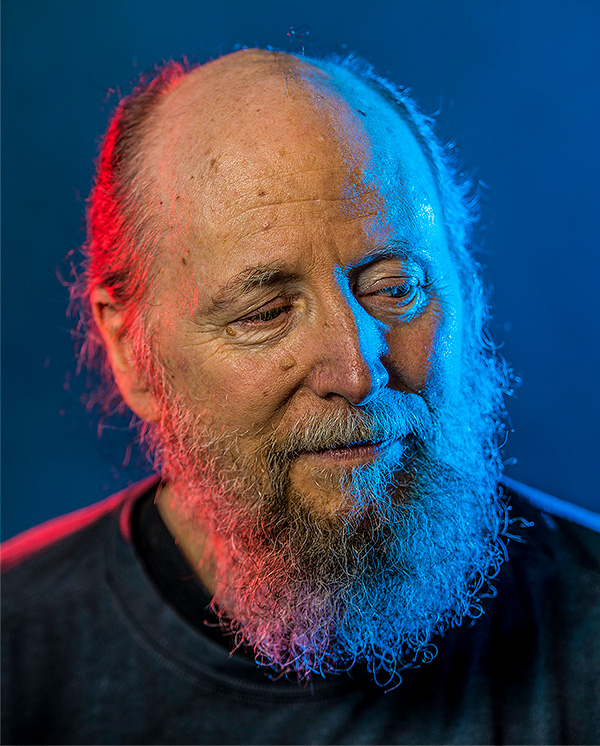

Canadian surgeon John Dushinski stands at the Qalandiya checkpoint, a major crossing point on the West Bank, waiting to travel between Ramallah and Jerusalem. It's the fifth time the Calgary urologist has travelled to the West Bank to perform surgery on Palestinian patients. Photo by Heidi Levine

To a layperson, the qualities of a great surgeon begin with steady hands and an unflappable disposition. The latter is evident in John Dushinski, '84 BSc(Spec), '91 MD, as he relaxes in his room at the Palestine Red Crescent Society's guest house in the Palestinian city of Ramallah after a long day in the operating room. Someone else might be infuriated under present circumstances, but Dushinski is calmly munching Cheezies he has brought from home as he Skypes with his wife, Brenda, who is back in Calgary with the couple's two teenage children. Husband and wife exchange thoughts on what might be done to expedite the release of a half-dozen suitcases full of medical supplies destined for a Palestinian hospital, which were confiscated by Israeli customs officers when Dushinski arrived at the Tel Aviv airport. "I told them they were donations, not goods for sale, but they took them anyway," he says with a shrug. He bids Brenda goodnight and ends their Skype call.

After a day in the operating room in Ramallah, the de facto capital of the West Bank, Dushinski relaxes and catches up on emails in his room at the Palestine Red Crescent Society guest house. Photo by Heidi Levine

It is June 2015. This is the urologist's fifth medical mission to the West Bank in 10 years, and it's the first time he has ever had his medical equipment seized. The confiscated suitcases contain supplies central to the purpose of his visit: to train doctors at Ramallah Public Hospital in urological surgery to treat conditions of the urinary tract and male reproductive organs. Since his last visit here, Dushinski has collected an assortment of instruments and supplies, including a number of laparoscopic cameras and digital imaging processors, that have been recycled or deemed obsolete in Canada but are much coveted here in the West Bank, where the Palestinian medical system is chronically strapped for resources. Air Canada even waived its usual excess baggage charges to facilitate the donation. Frustrating as it was to lose this material, worth between $100,000 and $150,000 purchased new, Dushinski's time is limited and he can't wait for the suitcases.

Dushinski is actually "John" to me. Our wives are sisters, and this is our second trip together to Ramallah, the de facto capital of the West Bank, 10 kilometres north of Jerusalem. We both feel pulled to this part of the world, though our interests developed in different ways and at different times. In my case, I have returned whenever possible since finding my way here as a backpacking 18-year-old during a gap year after high school. On this visit, I've come to Ramallah to learn more about the work of my brother-in-law. Like John, I am fond of Arab food, the Palestinian people and their culture, and even the arid landscape of the West Bank with its stony fruit orchards and olive groves.

Dushinski prepares for surgery on a 10-year-old Palestinian girl at Ramallah Public Hospital to remove a stone from her right kidney. Photo by Heidi Levine

Nothing symbolizes the Palestinians' connection to their land more powerfully than the olive tree. Short and squat, yet beautiful with its silvery green leaves and twisted and pitted trunk, the tree provides a staple of the local diet and, for many Palestinians, an important source of cash-crop income. But it's more than that. Olive trees live for a long time - from 400 years to as long as 800 or 1,000 years - and can take more than a decade to mature. As a result, Palestinian tradition holds that olive farmers of today owe gratitude to the generations that came before. And the trees they plant now are a passing on of that gratitude to future generations.

Early in the morning, we jump in the car with Qais Hamaideh. Dr. Qais, as he's known to Dr. John (physicians here refer to each other in this formalized first-name basis), is a friendly young urologist who swings by the guest house each day to drive the visiting Canadian up through narrow, winding roads to the Palestine Medical Complex in the heart of Ramallah, which sits atop one of the city's many sun-baked hills. The compound is bustling with medical staff, patients and their families this morning. As we walk across the parking lot, people overhear Dushinski reviewing the day's schedule with Hamaideh and smile. This feels like a hopeful, healing place.

Dushinski (right) and Palestinian surgeon Murad Barakat don surgical gowns in preparation for their first surgery of the day. Photo by Heidi Levine

Dushinski is doing what he can to make it so. Using two weeks of vacation time, he has come to Ramallah to teach a handful of urologists and residents how to perform percutaneous nephrolithotomy, a minimally invasive surgical approach to removing large or irregularly shaped kidney stones that, until surgeons remove them, can result in severe pain, infection and blocked urinary flow. It might be a mouthful to pronounce, but the procedure is small and delicate. It involves making a one-centimetre incision in the patient's back and then running a channel from that incision down into the kidney with a hollow needle to allow for the breakup and removal of kidney stones. A patient's only alternative is open surgery, which brings a higher risk and much longer recovery time, or transfer to hospital in Israel or Jordan for an endoscopic procedure at the cost of roughly C$5,000 per case - money the Palestinian Authority, which pays for the outside treatment, can ill afford. Hamaideh and his colleagues have lined up a long list of patients for Dushinski to see during his stay. "I don't mind," he says. "I like to be busy when I'm here."

Dushinski is accustomed to being busy. Back in Calgary, he is known around the medical community as "the stone guy." Specializing in endourology, the minimally invasive treatment of kidney stones and other urinary problems, he operates out of Rockyview General Hospital and maintains one of the largest practices in the city. From 2002 to 2010, he also served as chief of urology surgery for the Calgary Health Region, and from 2007 to 2010, as chief of surgery at Rockyview Hospital. Fellow Calgary urologist and surgeon Bryan Donnelly, '82 MSc, describes him as "as good as anyone on the planet when it comes to removing stones."

Dushinski places a dilator over a guide wire. Photo by Heidi Levine

Not too shabby for a guy who was almost finished an undergraduate degree in genetics before the idea of studying medicine occurred to him. "I didn't have very good marks," he admits. "But I had a weird schedule in my fourth year - a three-hour break every Monday, Wednesday and Friday in the middle of the day. And I thought, 'What the hell am I going to do for three hours three times a week?' So I decided to study, which I had never done other than the night before an exam. All of a sudden my marks took off, and I thought, 'What do I really want to do?' " He concluded it was medical school.

It might seem surprising that he hadn't considered medicine sooner, given that his father, Les Dushinski, '60 MD, was a urologist. The elder Dushinski ran a general urology practice at Edmonton's Baker Clinic and worked out of the Royal Alexandra Hospital for many years, including 11 years as its chief of surgery. Even so, it was never presumed, or even suggested, that the son would follow in the father's footsteps. Les, who died of cancer in 2003, and Myrna Dushinski felt it was important that their four children explore their own paths. "He didn't try to talk me into urology," John Dushinski says. "It really wasn't until I did my surgery rotation that I thought, 'I want to do this.' "

It wouldn't be the last time he would look up to find that he was following a path laid out by his parents.

In 1993, Les and Myrna Dushinski, who was a nurse, took part in a Canadian medical mission to Ukraine. This was a couple of years after the fall of the Soviet Union, and the state hospitals they visited in cities like Kyiv and Lviv were by then pretty neglected. Myrna recalls seeing equipment that nobody knew how to use stored in the rat-infested basement of a hospital in Kyiv. Family lore has it that Les was handed a scalpel so dull it couldn't cut cheese, never mind a patient's skin. During the mission, Les instructed staff and also treated patients, one of them an eight-year-old girl named Elena, who had to wear diapers because she was born without a bladder or urethra. When the medical team returned home, Les worked with the Rotary Club to bring Elena to Edmonton for three successful reconstructive surgeries performed by a pediatric urologist colleague. "Les was always doing something like that - lots of volunteer work," says Myrna. She continues to be a dedicated volunteer. She has volunteered for more than 30 years at the Royal Alexandra gift shops, which raise funds for the hospital, and has managed the hospital's Robbins Pavilion gift shop since 2011.

The younger Dushinski came to volunteering much later and without a conscious connection, though he recalls being interested in his father's stories about the medical mission to Ukraine. "It was very interesting to hear his stories about the way medicine works in that part of the world," he says. "But if it did have an influence on me it was subconscious because I didn't come away from it saying I want to do that kind of work. It just sort of happened."

The surgical team, (centre L-R) Dushinski, Murad Barakat and Qais Hamaideh, speaks to the mother of a young girl who underwent surgery at the Ramallah Public Hospital. Photo by Heidi Levine

It occurs to me this is much like the olive tree: the way a new tree can stand for years, growing and reaching for the sky, before it begins to yield its fruit. The younger generation benefiting from the foresight of the previous generation.

Dushinski inherited a dry wit from his dad and a particular penchant for well-timed dirty jokes (no examples of which will be repeated here). His fearless sense of humour is disarming and helps explain his popularity with colleagues in the operating room, be it at the Palestine Medical Complex or back home at the Rockyview. This morning, Hamaideh and chief of urology Murad Barakat enjoy a one-line zinger delivered at the expense of a tardy anesthesiologist as they wait to start surgery on the day's first patient, a middle-aged man with a several sizable stones in his right kidney.

I've been invited to don a gown, a disposable cap and booties and a lead apron to protect me from the X-rays used to image the kidney, and enter the operating room to watch. One of first things I notice are the gardening shoes Dushinski is wearing under his cloth booties. He brought them from home, he tells me, explaining that he started to wear them because he got tired of having good leather shoes ruined by irrigation fluid and other spillage from the operating table. Sure enough, we are barely into the morning's first operation when a plastic bag full of runoff irrigation liquid and blood bursts open beneath the table, splashing over the floor at Dushinski's feet. It prompts him to turn away from the patient for a moment and give me a crooked smile.

As soon as the patient is sedated and the procedure begins, I see one of the reasons for the respect Dushinski gets in the OR. He's good at his job. His qualities as a surgeon are on display: dexterous hands, an even temperament and instant recall of the precise anatomical and physiological knowledge required at any moment. First, he deftly demonstrates how to start a channel to the kidney through a tiny incision below the 12th rib, then moves aside and encourages Hamaideh to take over. When Hamaideh struggles to direct a long needle into the collecting system in the middle of the kidney, even I can sense his anxiety building. But instead of stepping in, Dushinski stares at the X-ray image of the errant needle on the monitor above the bed and coolly tells the Palestinian to pull back and try again. "Remember, push and release, just like you're throwing a dart," he says. Finally, Hamaideh hits what he's aiming at, and the task of breaking up and removing the patient's stones can begin. The Palestinian surgeon's confidence grows visibly. Later, Hamaideh tells me: "The main difference between John and others who come here is he allows us to work with our own hands. It sometimes seems like the others just want to show us their skills."

The view of the Al Amari refugee camp in the West Bank from Dushinski's guest house. Photo by Heidi Levine

But Dushinski will flash a sharp edge when it's needed. At one point during the procedure, he scolds a distracted doctor in the OR for answering his cellphone instead of concentrating on running the C-arm, which provides the surgical team an X-ray image of the patient's kidney. Later, Dushinski tells me about feedback he gave a day earlier to a surgeon who insisted on continuing to pulverize a partially broken stone with a lithoclast (think of a tiny jackhammer inserted into the kidney) instead of extracting it when Dushinski advised. The misstep inadvertently pushed some larger pieces of the stone too far into the kidney to be reached along the channel. "You've done this procedure, what, four times now?" Dushinski reminded the urologist when the two of them were alone. "I've done it 4,000 times. So the next time I tell you this is the way we should do it - this is the way we do it."

Dushinski's first trip to Ramallah was in 2006. It came about through the convergence of casual discussions with some urology colleagues in Calgary about someday doing overseas work. And he learned that my wife, Karen Hamdon, '79 BA, a longtime volunteer in humanitarian work, was hoping to take some Canadian doctors to Palestine. "At some point the conversations merged, and we began to plan our first trip," Dushinski says. His wife, Brenda Dushinski, joined him on that trip and has been on every mission except for this one.

He describes his initial mission to Ramallah as exploratory. "They didn't have any endoscopic equipment, but I looked through a cardboard box of stuff that had been left behind and eventually found enough pieces to build a resectoscope," used to remove diseased or damaged tissue from the uterus, prostate, bladder or urethra. Dushinski used it to do two transurethral resections, one to remove a bladder tumour and one to relieve the urinary problems caused by an enlarged prostate. On his second mission (made with colleague Bryan Donnelly and his wife, Evelyn, who is also a physician) Dushinski taught the Palestinian surgeons how to perform the procedure properly - meaning with something other than a jerry-rigged scope. His lessons evidently stuck. Ramallah Public Hospital is now the referral centre for the entire West Bank. When he visited in 2013, he introduced them to percutaneous nephrolithotomies. "That trip they mostly just wanted to watch," he says. "This time they wanted to learn how to do it themselves."

There are serious challenges to developing local capacity to undertake complex surgery in a place like the West Bank. Limited opportunities for advanced training, a dearth of supplies and equipment (twice on this mission a malfunctioning C-arm forced Dushinski's team to move to an OR in another hospital in the medical complex), plus the volatile political situation - all hinder the learning process. Still, Dushinksi's assessment of the Palestinian doctors' progress is positive. "I've seen an improvement in their surgical technique. I think they're at the point where they can try doing it on their own," he says. "It was like this two trips ago when we were trying to teach them transurethral resection. We were a little nervous about leaving and not knowing how things would turn out. Now they're the referral centre for the procedure. Hopefully, the same will go for percutaneous nephrolithotomy."

And the Palestinian doctors praise Dushinski. "We love him. In spite of a lot of difficulties, he is trying to train our colleagues here in Palestine. Otherwise, we would have to send them to Canada or to other places," says Rashid Bakeer, the recently retired chief of urology at Ramallah Public Hospital who oversaw all of Dushinski's previous trips. "Two weeks with him is the equivalent of one year with someone else," Hamaideh tells me. "He gives us many fine details and tips from his experience that you can't get from medical books. From the first time John came, he is like a model for me. Since then I've been doing things his way, even giving orders the same way."

As the end of Dushinski's stay approaches, he and his Palestinian colleagues have tallied close to two dozen stone procedures, and likely could have done more if they had had the supplies he brought. In Canada, the procedure he's teaching typically involves placing a surgical balloon over the hollow needle inserted into the channel, and then inflating the balloon to widen the channel enough to remove the stone. The urologists at Ramallah Public Hospital had exactly one balloon when Dushinski arrived (and he believes it was an undersized demo model, at that), which the team carefully used, sterilized and reused until it finally broke during a procedure halfway through his visit. From that point on, the team had to employ sequential dilators - inserting increasingly large pieces of rigid tubing manually - to dilate the channel, which is more time-consuming and damaging to the tissue. Meanwhile, in one of the confiscated suitcases, there are 173 dilating balloons.

Dushinski stops to speak to a shop owner in Al-Manara Square in Ramallah. Photo by Heidi Levine

The last patient on Dushinski's caseload is an elderly woman who arrives at the hospital with a painful kidney stone larger than a golf ball. The Palestinian urologists have to park their skepticism in the face of his insistence that even a stone this size can be safely broken up and taken out through a nephrolithotomy; the patient had been told that, even in Jordan or Israel, it would require open surgery. Sure enough, the procedure goes smoothly. That night, the woman's grateful son insists on taking Dushinski and Hamaideh out to a friend's restaurant for musakhan, a traditional Palestinian meal of roast chicken, caramelized onions and sumac, to express his thanks. It is the Arab way.

The following morning, Dushinski's last in Ramallah, I accompany him and Hamaideh on post-surgical rounds. They stop in to see the woman with the giant stone, a few chunks of which now sit inside a specimen bottle on her night stand like a strange yet satisfying souvenir. Dushinski picks up the specimen bottle and rattles it loudly for everyone's amusement. The happy patient, surrounded by relatives, smiles up at him from her bed and says something in Arabic. Hamaideh translates for Dushinski. "She says we are all one family now."

That evening over a couple of bottles of Taybeh, a very good Palestinian beer, we sit on the breezy balcony of a friend's apartment halfway down the main road between Ramallah and Jerusalem, and Dushinski reflects on this latest mission. The melodic and always stirring azaan, the Muslim call to prayer, drifts across from a nearby mosque. Suitcase problems notwithstanding, Dushinski deems the trip a success. He and the Palestinian urologists are already talking about his next visit. They want to learn how to perform laparoscopy, sometimes called belly-button surgery, on the kidney. "It has been an evolution, and it's hard to stop once you get started," Dushinski says. "Our first trip here was basically just getting to know them, knowing what their capabilities were and planning for the next trip. Now you build on that with every trip."

A Palestinian boy arranges watermelons for sale in Ramallah, West Bank. Photo by Heidi Levine

Overseas volunteer medical work in a conflict zone is not easy. Donnelly says he found the political situation on the West Bank unfair and maddening, though he and Evelyn still hope to return on a future mission. For Dushinski, the seeds sown by his parents' example, even if imperceptible at the time, have grown into something strong and solidly rooted. Donnelly believes his colleague's underlying drive in making these trips is the best one possible: "He wants to make a difference." After watching him work, it is clear to me that Dushinski does make a difference: as a healer and as a teacher and mentor. "The personal satisfaction you get from going somewhere and doing something that people there wouldn't have access to is huge. You can't quantify it in terms of the money that you make or the income you lose. It's just a good feeling," Dushinski says. As for the politics, he has his own views but makes it clear he's here only for humanitarian reasons.

When they gather for a little party to say goodbye to Dushinski at the end of the visit, the staff at the hospital present him with a young olive tree, carefully planted in a pot. There is no way he can take it home with him, and it wouldn't survive in Calgary even if he could. So he leaves it in the care of a Palestinian friend who works for the Red Crescent Society. She is going to plant it in the garden of her family's home, where it will be waiting for him to check out its progress on his next trip, and the trips after that. Given the significance of the olive tree to the Palestinians, the gift is a touching sign that Dushinski's hosts feel the Canadian doctor truly belongs here now.

Postscript: One month plus a day after Dushinski returned to Calgary, his suitcases were released by the Israelis. Their contents are now being put to good use by the urology department at Ramallah Public Hospital until Dushinski comes back to the West Bank, undoubtedly bringing more suitcases.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.