It wouldn't surprise any of travel writer Debra Cummings' friends to hear that she was in Scotland. But it certainly surprised Cummings when her home phone started ringing off the hook with calls of concern about her welfare. It quickly became apparent that someone masquerading as the Calgary-based Cummings was appealing to her friends from Scotland for money via a grammatically fractured e-mail.

The e-mail her friends received begins: "It is me Debra Cummings and this is coming directly from me." It goes on to say she is stranded in Edinburgh after losing her wallet, credit cards and cellphone. "I will like you to assist me with a soft loan of sum of 2,500USD urgently or any amount you can afford (No amount is small please) so as to sort-out my hotel bills and get myself back home immediately." The appeal was sent to some 1,500 contacts in Cummings' Gmail address book, prompting a quick flood of phone responses. One caller quipped: "So when did English become your second language?"

None of Cummings' friends were taken in by the clumsy scam letter, but the scenario could have played out with far more dire consequences if, she says, the perpetrators had crafted a more sophisticated story. Whoever tapped into Cummings' Gmail account also locked her out of her own account and had access to more than 5,000 messages in her mailbox, many filled with identifying details about her family, her interests and her life.

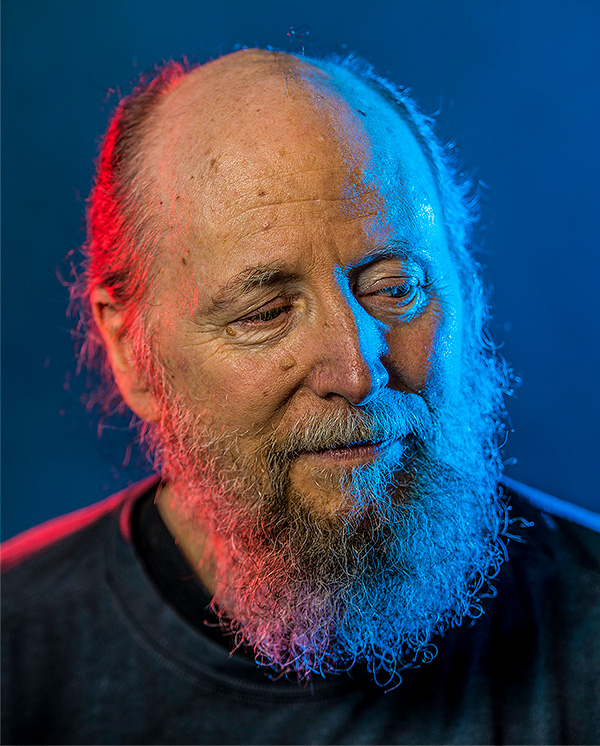

For Joanne McNeal, '82 MEd, having her online identity compromised had more severe consequences. In January 2010, she received a series of persistent messages about her Yahoo e-mail account seeking "verification" of her name, address and password. Late one night, when yet another warning notice arrived, she let her guard down and surrendered the data.

"I certainly learned how fast your information can be just blown wide open," says McNeal, who teaches in the U of A's Faculty of Education. Soon, financial appeals ostensibly from her were made via e-mail to family and professional colleagues in places as diverse as Africa and Saudi Arabia to the University of British Columbia and the Smithsonian Institution. Some were taken in by the scam, including a professor in Vancouver and a former neighbour in Virginia.

McNeal now shares her identity theft experience with her class of future teachers in the hope that the classroom discussion it prompts will serve as a wake-up call for the students. "Most of us are too trusting," she says. "When something like this happens, you have to learn from the experience."

Identity theft is one of the fastest growing crimes in the world. The Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (PhoneBusters) received over 11,000 reports of identity fraud in 2010. But law enforcement officials say that national figure is just a tiny fraction of the problem, with many cases logged in police files as commercial crime or fraud. Altogether these offences are now thought to be as profitable as drug-related offences, estimated at between $10 and $30 billion annually in Canada.

Cummings is sheepish about her role in the identity theft incident. She knowingly allowed her anti-virus protection to expire, making her computer vulnerable to those who troll the Internet looking for unprotected prey. But she's not unlike many cyberspace citizens who are often blasé about privacy.

The convenience of free social media has a personal information price tag.

In 2010 U.S.-based data security provider Imperva analyzed 32 million user passwords that were posted to the Internet after a hacker attacked RockYou.com, a company that makes applications for social networking sites. Despite years of warnings about the need for complicated passwords, investigators found that most computer users were embarrassingly uncreative in their online protection. The most popular entry code was 123456, followed by 12345 and 123456789. Many people simply use "password" or the name of the site being accessed. QWERTY, the first six letters at the top of a keyboard, was also popular.

The troubling data does not end with the RockYou.com examination. Other studies have also found that more than half of consumers use the same or similar passwords for all websites that require log-on entry. These patterns are welcome news to hackers who are increasingly using more password-cracking software. Security is only part of the equation. There are growing concerns about privacy and what consumers are giving up on a regular and irretrievable basis.

We have become addicted to the convenience of free social networking sites such as Facebook and YouTube. But the old chestnut that "nothing comes for free" still holds true in the 2.0 world. The convenience of free social media has a personal information price tag. For instance, Google offers consumers Gmail and Google maps at no cost but, in return, the Internet giant gathers information it uses to individualize advertising pitches.*

"Google targets advertising based on the contents of your e-mail," says Gordon Gow, who teaches communication and technology at the U of A's Faculty of Extension. "That's the bargain of Google."

Those who are adamant about protecting their data can choose not to use social networking sites, or even the Internet, for that matter. But opting out is increasingly difficult (and impractical) in a wired world. Meanwhile, online collection of personal information has increased exponentially. Statistics Canada found that in 2009, one in three Canadians with Internet access posted content to the web. In January 2011, Facebook had more than 600 million active users, while there are more than 500 million Hotmail or Gmail accounts worldwide. Money matters are also changing. A decade ago, many people were leery of buying anything over the Internet. But, in a 2007 study, Statistics Canada revealed that 8.4 million Canadians spent $12.8 billion on online purchases.

Gow says the public has become accustomed to online convenience and shopping is part of that package. People trust that merchants will look after the security of the transaction.

"The convenience of using credit cards and e-commerce often outweighs any privacy concerns consumers have at the moment," says Gow, adding that consumers tend to go to the sites they expect will be safe. "The Amazons and RBCs of the world are working within the accepted privacy practices."

But there is always an element of risk, a chance that a hacker has set up a fake site. And it only takes a few victims to make the scam profitable. "There's a huge black market once credit card information is stolen," says Gow, noting that the financial impact can be fast and devastating. In the time it takes to read this article, a criminal can run up tens of thousands of dollars in bills and be on to the next target. Canadian law enforcement officials are trying to develop a national strategy on identity theft, but it's difficult.

"It's like chasing a moving target," says Sergeant Sylvie Tremblay, coordinator of the RCMP's identity fraud unit in commercial crime. Most of the culprits are hiding behind computer screens outside Canada, sending e-mails in hopes of getting a nibble from a naïve victim willing to part with private details.

In May of 2010, Gmail users in India received a "legal" notice supposedly from the Gmail team asking that a collection of personal details be updated as part of a security verification process. The kind of request - known as phishing - was seeking the user's occupation, birth date, country of residence and, of course, account password. The notice also warned that users who failed to provide those details within seven days would lose their account permanently.

Once that information has been surrendered, there is no simple way to stuff it back in the cyber bottle. McNeal found that even her Facebook account was compromised, and, in a chilling twist, several of her friends reported carrying on Facebook conversations with the imposter who was seeking money for a supposedly stranded McNeal.

"You just feel violated, like you've been opened up, drawn and quartered," says McNeal. "Certainly, you learn you need to be vigilant and to not discuss personal information or passwords."

These feelings aren't unusual, says Jessica Van Vliet, a U of A educational psychology professor and one of the few academics to have studied the psychological impacts of identity theft. Each of the 14 victims who recounted their experience to Van Vliet expressed a pervasive sense of vulnerability each time they use a credit card or a bank machine. Most also felt financial institutions were treating them as criminals.

The lack of specifics makes it difficult for identity theft victims to attain any closure and move forward.

Very few of the people in Van Vliet's study had sought any counselling. But that doesn't mean the experience isn't traumatic, only that identity theft may not be well enough understood by the general public who often take years to realize some issues can have lingering effects.

In a coordinated effort to combat identity theft, law enforcement officials assembled a framework that connects the resources of police departments, different federal agencies, credit bureaus and financial institutions, but Tremblay stresses public education is the other key component in any fight against identity theft. Although criminals have focused on middle-aged consumers with established jobs, bank accounts and credit ratings, Tremblay warns that young people now in university who have grown up posting their lives online could be the next target.

"We're not keeping up with educating them," says Tremblay. "We need to educate the youth to withhold information." But convincing people to change their social networking habits and online purchasing behaviour is a tough row to hoe.

As con artists become increasingly sophisticated, creating dummy company websites and sending "security verification" e-mails that can seem very legitimate, the best advice to avoid being a victim of identity theft is this: Don't be shy about asking questions to verify that a website or e-mail is authentic. Take the same precautions that you would with a stranger at your door.

* The U of A has teamed up with Google to provide e-mail to everyone on campus - a move that can save the U of A up to $2 million. Google won't own the content, and, unlike public accounts, it won't be allowed to scan through the text, nor will advertising or data-mining be sanctioned.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.