A University of Alberta student is part of a team of researchers who have just published an in-depth study of a stunning find: the first tyrannosaur embryo fossils ever discovered. The results shed new light on how the iconic dinosaurs grew and developed.

“Tyrannosaurs are represented by dozens of skeletons and thousands of isolated bones or partial skeletons,” said Mark Powers, second author on the study and PhD student in the Department of Biological Sciences. “But despite this wealth of data for tyrannosaur biology, the smallest identifiable individuals are aged three to four years old, much larger than when they would have hatched. No tyrannosaur eggs or embryos have been found even after 150 years of searching—until now.”

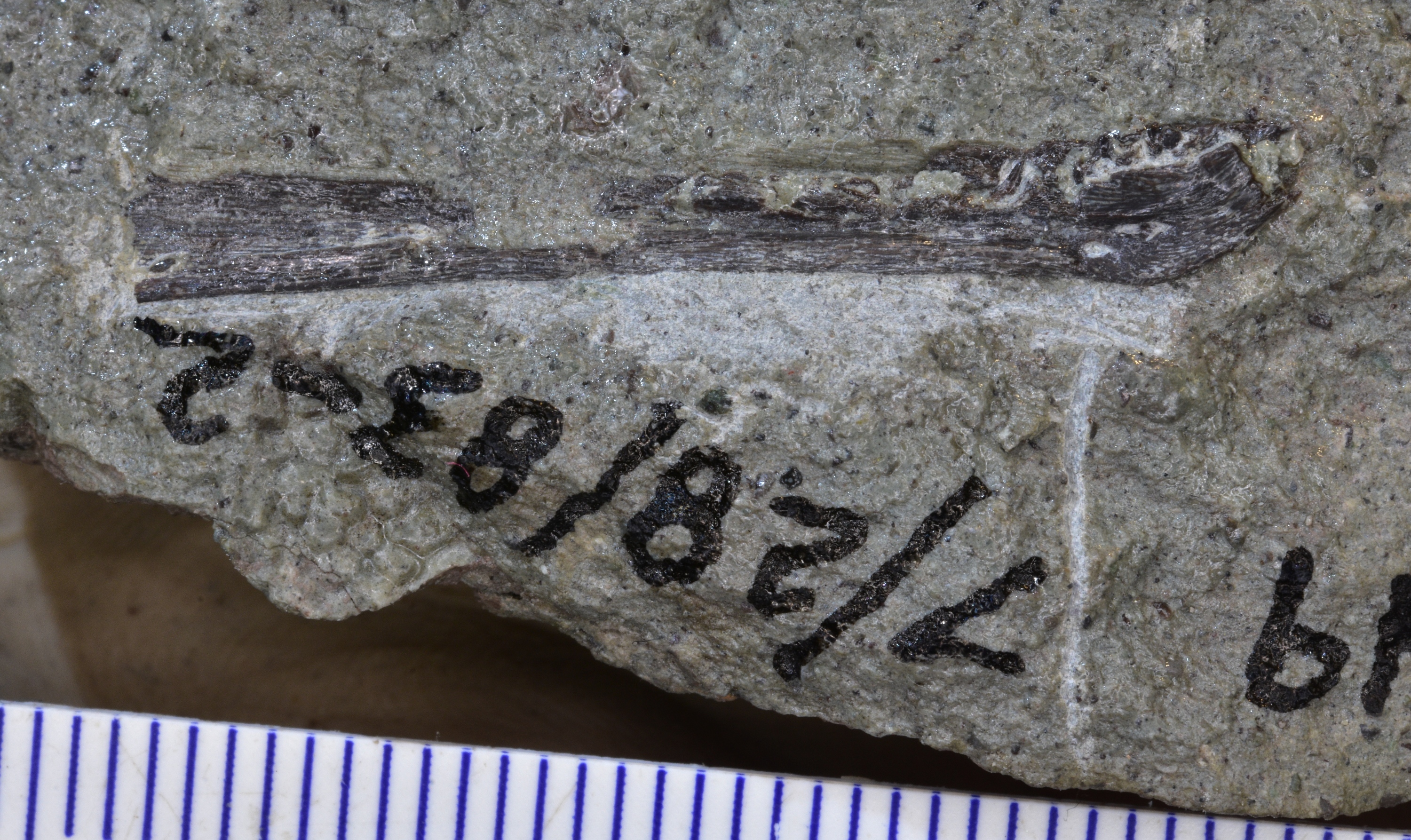

The study, led by U of A graduate Greg Funston, focused on two fossils of interest: a small toe claw of an Albertosaurus sarcophagus found near Morrin, Alta., and a small lower jawbone of a Daspletosaurus horneri found in Montana. The claw is roughly 71.5 million years old, and the jawbone roughly 75 million years old.

“The discovery of embryonic material is a huge find in our efforts to understand how some of the most popular and charismatic dinosaurs began their life, and grew to immense sizes,” said Powers, who completed the research as a master’s student under the supervision of Philip Currie. “It provides a much-needed—and until now, missing—data point depicting the starting point for tyrannosaur growth.”

From tiny to tyrannical

Powers said the unprecedented finds have a lot to teach researchers.

“There were two surprising results. The first is that the small tyrannosaur teeth were distinct from the teeth of older individuals—having not yet developed true serrations along the cutting edge of its teeth, as is iconic of the juveniles all the way through to adults,” he noted.

The second was the estimated size of the embryos. The specimen belonging to the toe claw was estimated to be about 110 centimetres long, while that of the jaw bone was about 71 centimetres.

“Amazingly, the size estimates match well with a hypothetical hatchling proposed by the late American-Canadian paleontologist Dale Russell back in 1970. This attests to Dale Russell’s insight into tyrannosaur development,” said Powers. “This was an unexpected but surreal result, as the study was published in a special issue of the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences honouring Dale Russell for his contributions to the field of paleontology.”