If there is a singularly satisfying sound that a flying watermelon makes when swatted by a lightsabre, collaborators on a virtual reality exercise game called Slice Saber will find it.

The game’s University of Alberta creators and their counterparts from Japan are hoping the sound — along with a host of other gratifying noises and visual and sensory effects — will get otherwise sedentary people exercising and having fun.

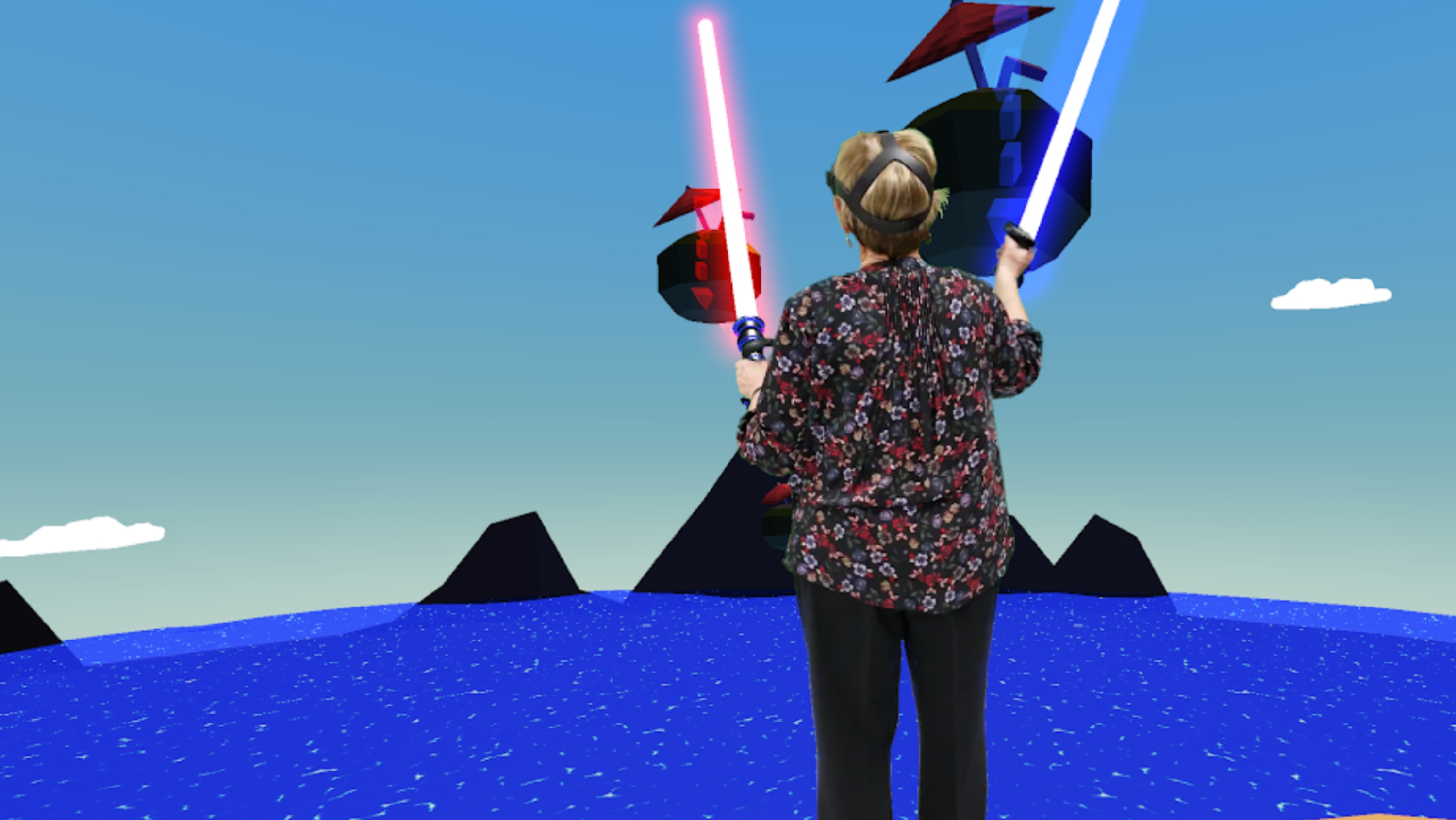

Slice Saber is one of a half dozen games available on Virtual Gym, an exercise platform on which health practitioners provide game-like physical activities for older adults, with configurations that match each user’s capabilities. Virtual Gym is created by a U of A computing science research team led by Eleni Stroulia and Victor Fernandez in partnership with the AGE-WELL Network.

To play, participants enter one of six different virtual worlds where they perform a range of stretches and movements to do everything from popping balloons, climbing mountains, shooting a bow or even slicing at a steady stream of flying fruit. The platform relies on the virtual reality headset to collect game-play data that evaluates the player’s performance and helps tailor the game to match each user’s capabilities in real time.

“In our case, we’re working with seniors who may not be able to go out to exercise, to give them an opportunity to maintain the flexibility, balance and level of activity that is good for avoiding frailty,” Stroulia says. “And while Japan has a much older population than Canada, they are hoping to deploy it in younger adults, not just seniors.”

Stroulia shared the platform, which is still in development, with counterparts at Ritsumeikan University in Japan who became interested in “exergames” during the pandemic, which continues to challenge the island nation and has led to increased isolation in citizens of all ages.

“Our Japanese colleagues proposed to make Virtual Gym more enjoyable and motivating for younger adults, which is particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, where people can be stuck at home.”

The group is experimenting with sound, visual and haptic (touch) effects across the platform, including improving the sound made by slicing watermelons and the physics of how they break when sliced by the user’s lightsabre.

The researchers aim to answer a number of questions, Stroulia says. “Will these changes make the game more enjoyable? Do people play longer? Does it make it easier to play?”

The genesis of this collaboration can be traced back over a decade. The relationship began in 2011, when U of A digital humanities professor Geoffrey Rockwell won a Japan Foundation grant to study Japanese video game culture at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto. “While there, we got to talking about the need to develop a dialogue about Japanese video games, as the fields of game studies in the West and in Japan weren’t talking,” Rockwell says.

The result of his visit, with the help of the U of A’s Prince Takamado Japan Centre for Teaching and Research, was a symposium in Edmonton in 2012. The successful symposium evolved into an annual conference, which would come to be known as Replaying Japan: International Conference on Japanese Game Culture. Designed initially to alternate between Japan and the West, it now includes researchers and destinations all over the world.

“Two of the three gaming console makers are in Japan,” Rockwell says, yet gaming culture researchers there were isolated from their global peers. “If you want to fully understand a major entertainment industry, you can’t do that without studying Japan.”

He adds that the strategic importance of this relationship has never been more apparent. Canada — on the strength of gaming design studios in Montreal, Vancouver, Toronto and Edmonton — is among the countries with the most video game design companies, trailing only the likes of the U.S., Japan and the U.K.

In an effort to strengthen this partnership even further, Rockwell, Stroulia and Fernandez joined University of Alberta president Bill Flanagan on a recent visit to Japan. On March 1, Flanagan attended Ritsumeikan University to sign a memorandum of understanding between the U of A’s Kule Institute for Advanced Study and the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies — Japan’s only academic centre focused on game studies.

“It is our hope that we can expand the connections between Japan and the University of Alberta so that we can work together to seek solutions to the world’s most pressing challenges,” Flanagan told attendees.

The U of A’s partnership with Ritsumeikan University dates back even earlier than Rockwell’s trip with the Japan Foundation. In 2010 the two universities signed the Visiting Student Certificate Program Agreement. Since then, 103 students from Ritsumeikan University have studied at the U of A. The institutions have worked together in multiple areas of research, with 16 publications co-authored to date, and have a history of collaborating as members of the Japan-Canada Academic Consortium. The U of A is home to the Prince Takamado Japan Centre for Teaching and Research, which serves as the Canadian Secretariat for the consortium.