Having returned from his role as Commonwealth election observer in Nigeria, Andy Knight says there is good reason to pay attention to the country’s evolution towards democracy.

In Africa, all eyes were on Nigeria’s Feb. 25 presidential election, he says, as it was considered a bellwether for the hope of free elections on the continent.

“It's the largest country in Africa (more than 200 million), and it’s wealthy, so other countries will follow what it’s doing,” says Knight.

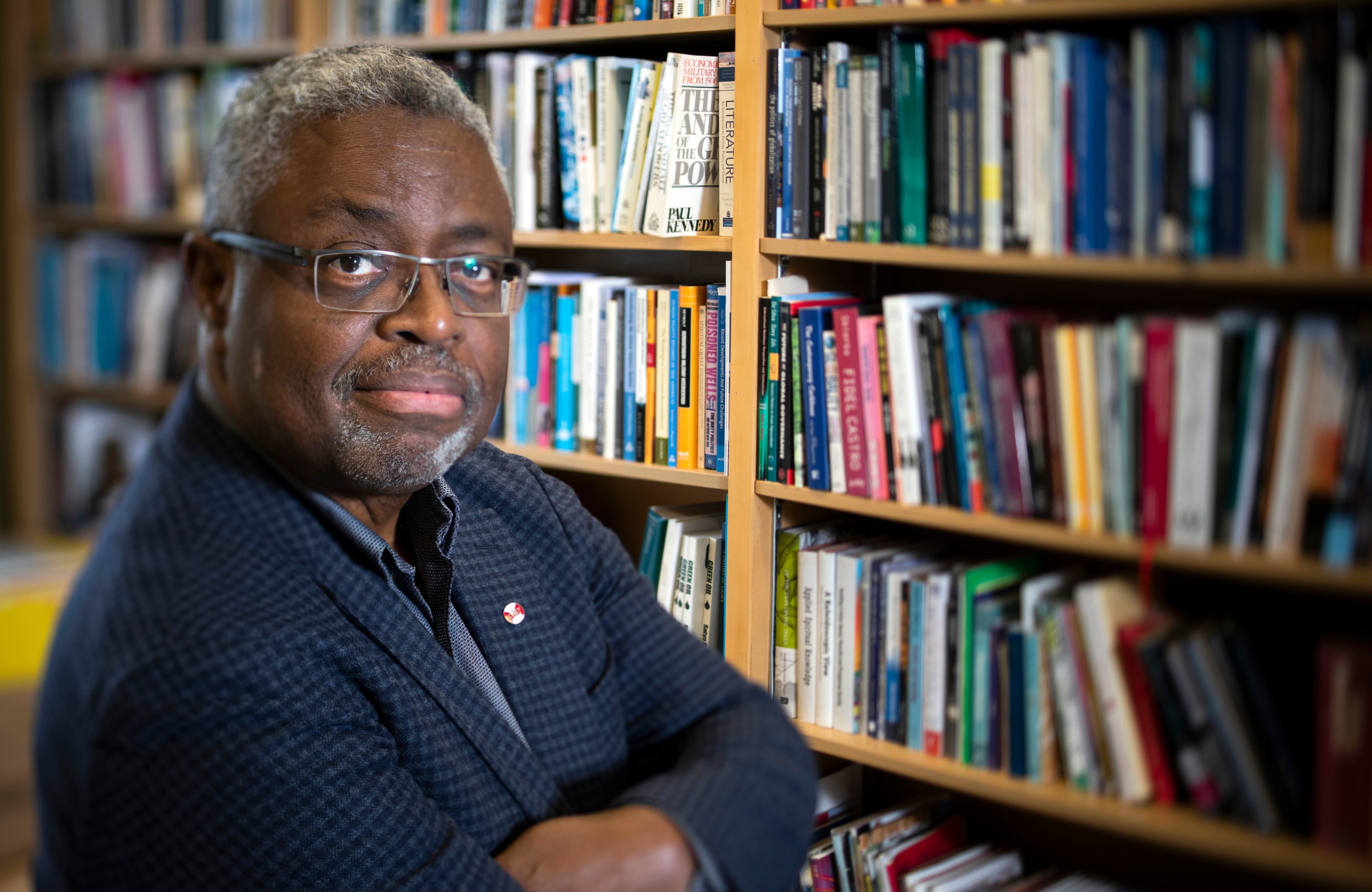

The University of Alberta political scientist and Inaugural Provost Fellow in Black Excellence and Leadership was selected to join the Commonwealth Group of Observers, a 15-member team headed by former South African president Thebo Mbeki.

While a number of groups monitored the election, the Commonwealth version has a strong reputation for integrity and for making positive recommendations for improvement, says Knight, which it will submit in the coming months.

According to the international press, Nigeria’s election was no shining exemplar. The Economist called it a “chaotically organized vote and messy count,” the Financial Times concluded it was “deeply flawed,” and The Guardian described the winner — Bola Tinubu of the ruling All Progressives Congress — as “an immensely wealthy veteran power broker trailed by corruption allegations,” including drug trafficking.

The Commonwealth group witnessed or heard reports of ballot-box stuffing, polls opening late, vote buying, voter intimidation and a colossal failure of the country’s new electronic voting system. With only 29 per cent of the population registered to vote, Tinubu took just 37 per cent of their votes to be elected president, a result now being contested by the leaders of the opposition.

Cause for optimism in a young democracy

Despite the many problems — none of which were new or unexpected, says Knight — there is still cause for optimism. Mbeki reported that Nigeria’s 2023 general elections were “largely peaceful” and that “Nigerians were largely accorded the right to vote.”

As only the seventh election since the end of military rule in Nigeria in 1999, the elections were far from perfect. “But the hope is they can improve next time around,” Knight says.

“We need to give Nigeria some slack. It is a young democracy in relative terms. Its problems are no different from some more long-standing democracies.”

One big disappointment was the lacklustre participation of young people in the election. The buzz on social media beforehand indicated considerable enthusiasm for Labour candidate Peter Obi among youth. But on voting day the vast majority of them — 80 per cent — failed to show up.

“Peter Obi is the most popular politician right now in Nigeria, at least on social media,” says Knight. “He didn't get the votes he thought he was getting, because young people just didn't vote in the numbers expected.”

Obi nonetheless called on the youth to be patient and refrain from post-election violence in dealing with their disappointment in the election’s outcome, says Knight. Instead, he urged them to let the courts decide on the Labour Party’s challenges to the outcome.

Intimidation was a huge factor, says Knight, with street gangs discouraging youth from voting. Another was the failure of the new bimodal electronic voting system, advertised as the answer to ensuring a free and fair election.

Systemic problems persist

Another huge problem in Nigeria is the country’s deep and systemic misogyny, says Knight, which discourages women from entering the political fray. It is a culture partly responsible for the rise of Boko Haram, one of the world’s deadliest terrorist organizations.

In a 2016 study, U of A sociologist Temitope Oriola wrote that "Boko Haram's sexual violence against women is articulated as a reflection and extension of mundane gender-based violence all too common in society.”

Guided by the extremist ideology of both evangelical Christians and devout Muslims, “the dearth of women in key political positions will persist as long as both religious sects remain dominant in Nigerian society,” says Knight.

Another challenge is that Nigeria, like many countries around the world, is hardly immune to election interference. In his role as observer, Knight asked representatives in all parties whether they were worried about it.

“The answer was usually, ‘Not really, we think we have this under control.’ But the reality is that, as we’ve seen, countries like China, India and Russia can find ways to intervene in elections. It's important for candidates to keep an eye on that.”

Nigeria’s struggle for democracy might seem distant and irrelevant to many in North America. But in Knight’s view, Nigeria’s elections are yet another litmus test for democracy’s very survival.

“It’s a long-term process — you’re not going to have democracy overnight. But you have to be diligent in supporting something as fragile as democracy, even if elsewhere. Otherwise, you can lose it.”