This year, Jonathan Schaeffer winds up his 40-year career as a professor in the Department of Computing Science. Jonathan is an expert in and pioneer in artificial intelligence (AI) at the University of Alberta and a fellow of both the American Association for Artificial Intelligence and the Royal Society of Canada. As a past dean of the Faculty of Science, he expanded the U of A’s reputation as a leader in AI and led U of A’s development of massive open online courses (MOOCs). His many achievements include the exploration of AI’s potential through the lens of games, including a still-unbeaten computer program for playing checkers, to co-founding the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute. Hear from Jonathan as he reflects on his last lecture, his love of teaching, how to get ready for AI and his full-time leap into entrepreneurship.

Looking back on your career at U of A what is your greatest accomplishment?

Scientifically, there's no question. It was working on the checkers project. When I started working in AI, I naturally migrated to working on games because I love playing games. And back when I started it was an open question as to whether you could build game-planning programs that were better than humans and when would that occur.

I began by working on chess programs. In 1986, I had a wonderful result, tying for first in the world computer chess championship. But three years later I stopped programming chess because some friends of mine, including Murray Campbell, a native Edmontonian and U of A alumni, were hired by IBM, becoming the Deep Blue team. They beat the reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov, in an exhibition back in 1997.

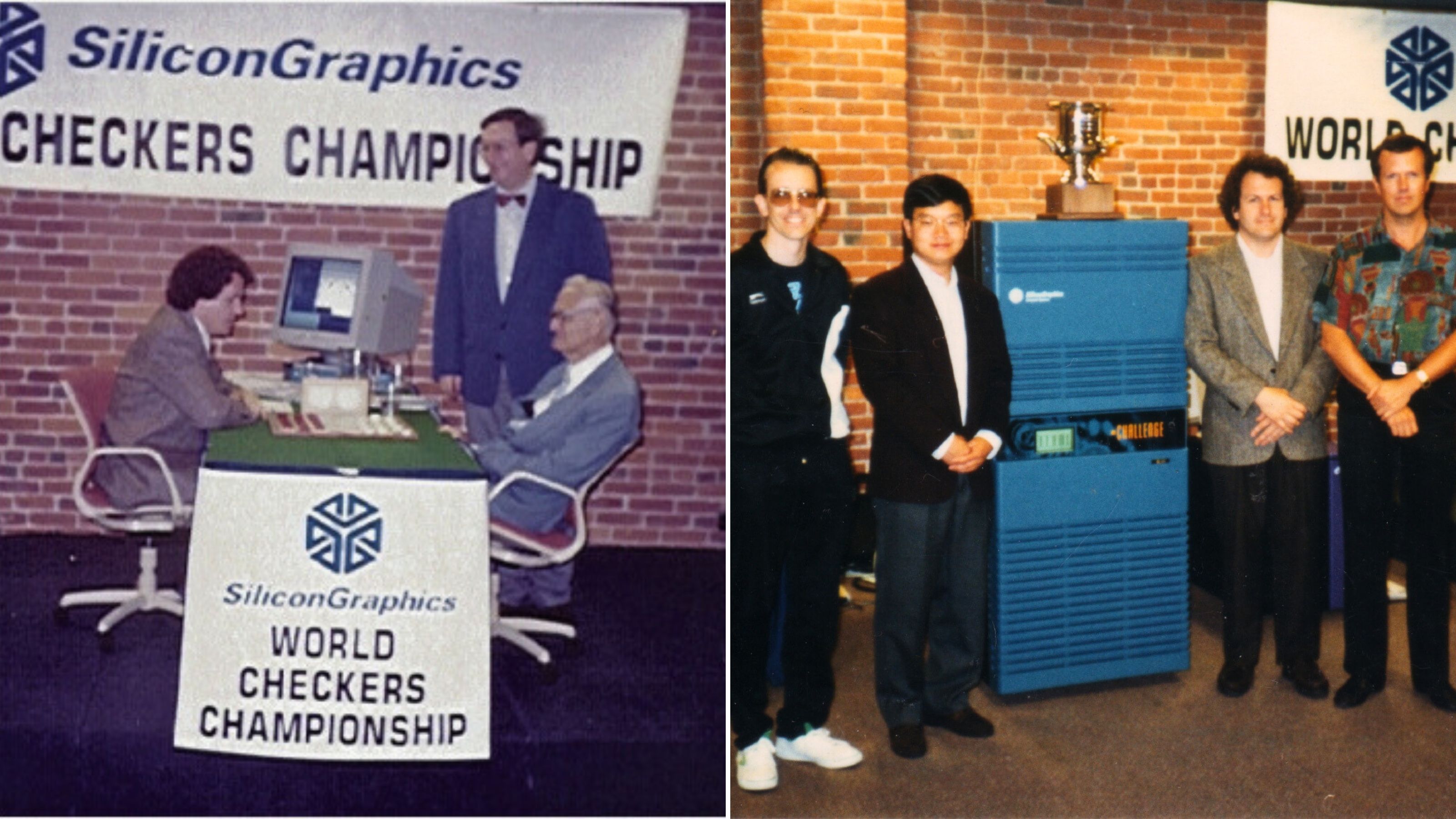

I moved on to working on checkers in 1989 because it had all the same research challenges as chess, but was a less complex game. In 1994 we became the first computer program, called Chinook, to win the World-Man Checkers Championship. This was the first time a computer won a human world championship in any game, and that was a milestone in the history of artificial intelligence.

I continued to work on the possibility of solving the game, to be able to play perfect checkers. Copies of my program started running in 1989 on undergraduate machines at the University of Alberta. I added hundreds of computers in California and then in Europe. I persevered and computers got faster and memories became larger. Instead of using one computer, I used hundreds at a time. They were all communicating back and forth, trying to solve the game of checkers. In 2007 the computations came to an end: checkers was solved and my program was now perfect. Perfect play by both sides leads to a draw… but the opponent has to play perfectly! Chinook will never lose a game of checkers again. That is one of my greatest scientific accomplishments, what I'm best known for, and I'm very proud of it.

Left photo: Chinook (Jonathan Schaeffer) squaring off against Marion Tinsley at the start of the second World Man-Machine Checkers Championship, Boston, 1994. Right photo: The Chinook team, winners of the second World Man-Machine Checkers Championship (from left to right: Martin Bryant from the UK, Paul Lu, U of A professor, Jonathan Schaeffer, Rob Lake, now retired from the U of A).

What will you miss most about working at the U of A?

I'm going to miss teaching and working with students the most. I love to teach. Put me in front of an audience on a subject that I know and am passionate about and you’ll have to shut me up because I am charged up. I've been privileged to supervise over 80 graduate students and work with a myriad of undergraduate students on various projects or summer internships. It's always fun because supervision is a form of teaching. It's mentorship.

Teaching is its own reward. I was in an airport recently, waiting for a plane in Vancouver and someone walked up to me and said, “Are you Professor Schaeffer?” And I said, yes. They said, “You taught me operating systems 10 years ago and it was the greatest course, and it inspired me. I got this wonderful job and the things that I learned in the class have made a difference. And I just wanted to say, thank you because that course really helped me in my career.” And you know what? That's the ultimate reward and this happens quite a bit.

You had your last lecture this past December. How was your last class of teaching?

Hurried? It was the last lecture and I was teaching CMPT 379 - Operating Systems Concepts. I was a little bit behind in the material, so I had to get through it all. It was rather emotional for me. The lecture has an odd sense of timing. When I was still a graduate student at the University of Waterloo, I drove to Edmonton, leaving on Christmas Day 1983 and showing up for my first day of work as a lecturer on January 2 teaching Operating Systems Concepts. By an odd coincidence, it's the same course 40 years later. A lot of the content changed, but it's the same course.

What is next for you?

People say, “Oh, Jonathan, you're retiring,” and the answer is, “No, I'm not retiring.” I don't want to sit around and do nothing. I've got lots of things I want to do. Myself and some partners started Onlea, a company, about 10 years ago. The On stands for online, and the Lea stands for learning. We build online courses like for the MBA program at the University of Alberta.

We're working on some exciting projects. I've done the university thing for 40 years and now I'm an entrepreneur, and we're building up a company. So I'm now half-time at the U of A and half-time at Onlea and at some point later this year I'll be full-time at Onlea. I like to say that I'm reinventing myself. I'm giving myself a new career path.

Looking back, what surprised you the most about your career?

Everything is about AI these days, particularly right now with ChatGPT. I've been asked to give numerous predictions over the years, and what surprises me the most is all the predictions have been wrong: they've been too conservative. Everything is happening much faster than I ever imagined it. I would never have predicted that tools like ChatGPT would exist so soon. Maybe in a decade or so, maybe, but not today. AI research is having an incredible pace of advancement and some impressive results.

As an expert in the field, how should people get ready for AI?

First, a problem with AI is that it affects everything. What I like to say is “AI and X. Choose your X”. For example, AI and music, or AI and medicine. Choose your X. It doesn't matter what your profession is, AI is going to impact your field. Everybody needs to get ready for AI-related change. AI is going to impact everybody.

The second thing is that it's happening rapidly. There are other kinds of technology humans adapted to over time, like the evolution from riding horses to using cars — that took decades. With AI, instead of change happening gradually over time, developments are happening daily. The concern is that governments are slow to react and appropriate laws aren't necessarily in place.

Public education is absolutely critical. It’s important that the population understands what AI technology is – and especially what it is not – and what it can do because it will transform our world. If we do it properly, it will transform this world in a positive way. When I say public education, I don't mean watching doom and gloom television shows where mankind battles AI robots that are out to conquer the world. No. I'm interested in a world where AI makes our lives better. You know the drive from Edmonton to Calgary is awfully boring. I want an autonomous vehicle: a driverless car. There's a simple example of where AI can make a qualitative difference in my life.

The point here is that the potential benefits of AI are enormous, and we, as a society, should be working towards harnessing this technology to make this a better world. Yes, there's always a downside to technology. We can consider evil emperors and countries who want to do terrible things using this technology. But you have to believe that humankind will follow the right path and not the wrong path, and I firmly believe in that.

Over the span of your career, how has the U of A changed?

Before I moved here over 40 years ago, I visited only once for a couple of days. I came here without knowing what I was getting into. At the time, it was a big university to me but in the global scheme of things, it was a provincial university. It was a smallish university that talked a good talk. But they didn't deliver on that talk, they weren't world-class. But over 40 years later and with some inspired past leadership at the university, the university became a global university. It's grown enormously. The quality of the research has grown impressively. Hey, we even have a Nobel laureate here!

When I started, we had a small computing science department. I think I was professor number 14 at the time. Now we have over 60 professors in our department, many of whom work in AI. We're truly world-class, one of the premier places in the world to go for artificial intelligence and machine learning research. It's been a great ride to be part of the team that built themselves up from nothing to being something that's truly on the world stage, and our department has many outstanding researchers. Although I'm moving on to other exciting things in my life, I am going to follow what our department does and what we do in AI, because we're on a roll!

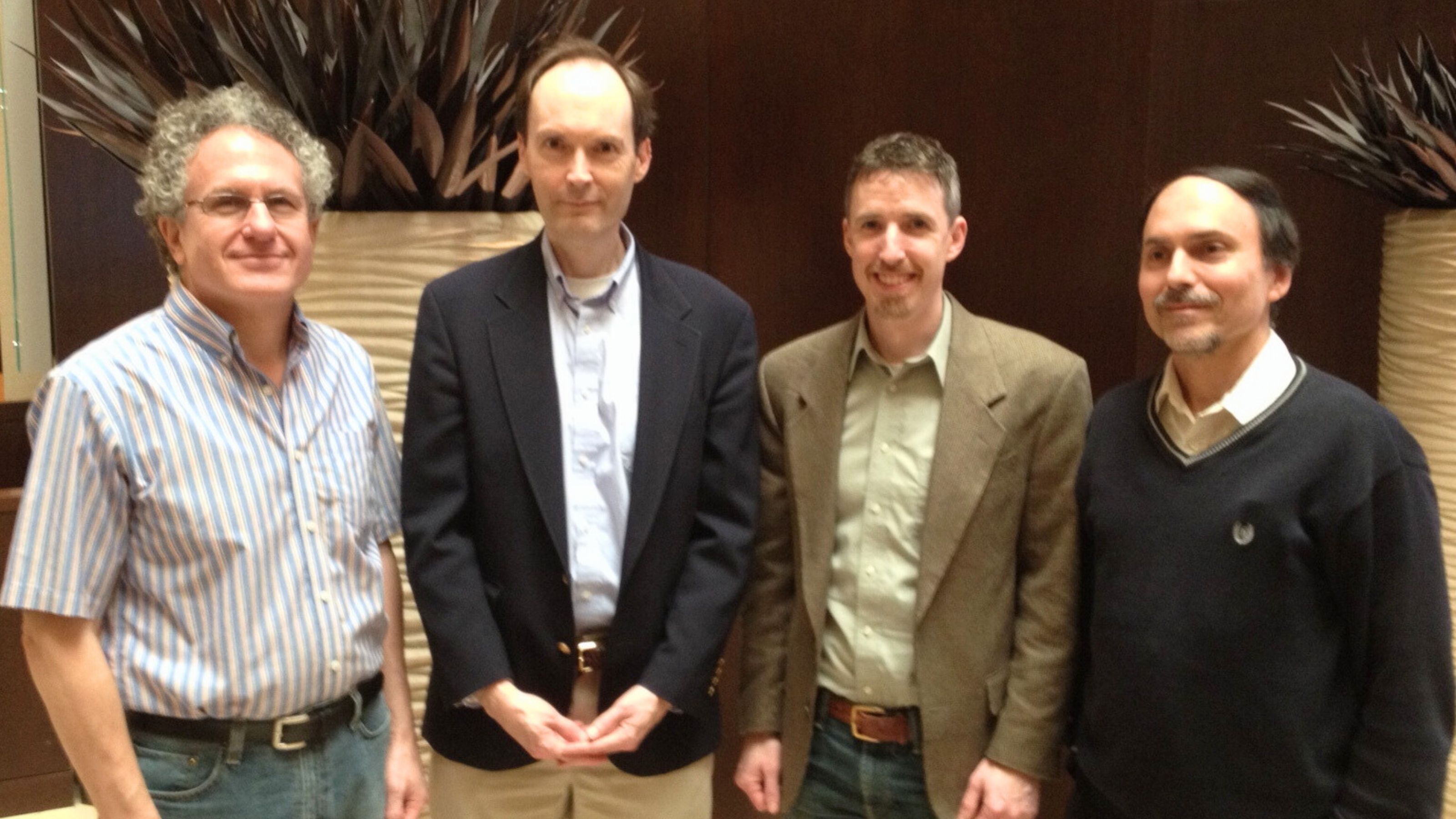

The Gang of Four, pioneers of computer games and AI, left to right: Jonathan Schaeffer (checkers, 1994), Murray Campbell (U of A alumni, chess, 1997 — Deep Blue team), Michael Bowling, U of A professor (two player poker, 2015) and Gerald Tesauro (backgammon, around 2000).