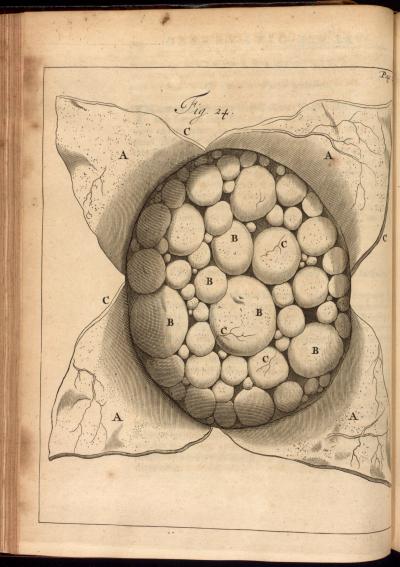

Engraving taken from Frederik Ruysch's Opera Omnia, 1639-1731. Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

Early Modern Illnesses and Treatments

Surgeries, Deformities and Disease

Complicated Pregnancy

by Lianne McTavish

|

| Hydatidiform Mole, Uterus. Engraving taken from Frederik Ruysch's Opera Omnia, 1639-1731. Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. |

It might seem as if such fundamental bodily experiences as pregnancy and birth would be similar over time, creating a common link between women of the past and the present. Yet early modern medical treatises, diaries, and baptismal among other records suggest that there are more differences than continuities.(1) As other entries on this Web site indicate, the body changes historically, and was distinctive during the early modern period. Early modern medical practitioners and lay people alike held a humoural view of the human body, understanding it to consist of various liquids that shifted or stagnated depending on a range of factors, including levels of physical activity, gender, sexual practices, and food consumption. Pregnancy was accordingly experienced in humoural terms, as an embodied activity that was unique to each woman, her particular temperament, and social conditions. Given the diversity of pregnancy, early modern medical practitioners cautioned against diagnosing it too hastily. According to the French royal surgeon Jacques Guillemeau, fellow male practitioners should be careful because ‘there is nothing more ridiculous than after having insisted that a woman is pregnant, to see her womb produce menstrual blood, or a quantity of water, or to hear various winds exit from it instead of a child.’(2) During the early eighteenth century another French surgeon, Guillaume Mauquest de La Motte, insisted that pregnancy could not be verified until the fourth month because before then the contents of the uterus were minuscule, and might consist of what we would now call a fetus, but could also be a mole [a mass of unformed flesh], water, wind, or retained menses.(3) The womb both produced and fostered a range of substances during the early modern period, eluding the identification of even the most prudent chirurgien accoucheur [surgeon man-midwife].

Some authors of obstetrical treatises recognized that women themselves were best able to diagnose pregnancy. The French surgeon Jacques Duval claimed that a woman could examine the texture of her own cervix to determine her bodily condition, and might also perceive her breasts becoming more firm.(4) She would more definitively feel the child quicken, or move within her womb, at about three or four months of gestation. Historian Barbara Duden argues that pregnancy remained a realm of female authority during the early modern period because only women could experience, name, and announce publicly their condition. Duden contrasts this historical form of female agency with the medical procedures that today have apparently made pregnancy an objective condition confirmed by hormonal tests and ultrasound machines.(5) The continued respect for women’s bodily experiences during the early modern period, along with the female celebration after a successful delivery, have led some modern women to look fondly at the past, considering it with a sense of loss and nostalgia, especially when they compare it with the sometimes cold hospital conditions in which many western women give birth today.

|

| Lying in Chamber Woodcut, 1583, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library |

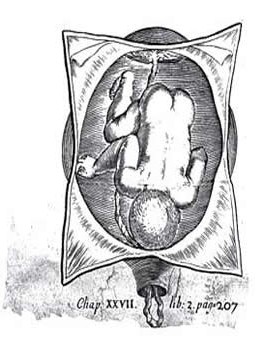

A typical early modern birth scene would include the labouring woman, her female friends, and a trained midwife. Some female midwives attained a relatively high status, including Louise Bourgeois, a French woman who wrote an obstetrical treatise first published in 1609 and delivered all six children of Queen Marie de Médicis. Yet historian Monica Green argues that male practitioners provided gynaecological services more regularly during the sixteenth century.(6) Men also became more active within the birthing room during the next century, not only in the major urban centres in France, but also in other parts of Europe and England. All the same, men remained unable to ascertain exactly what was inside the maternal body. Usually called to assist in difficult cases, when the child was in an awkward position or its head was impacted, male practitioners strove to determine its situation through the use of touch rather than vision. Guillemeau argued that assisting at unnatural labours was the most challenging kind of surgical practice precisely because men could see neither the body of the draped woman, nor the unborn child in her womb.(7) Later authors agreed that chirurgiens accoucheurs had to be equipped with especially skilled hands in order to discern the position of child in the womb by touch instead of sight.(8) Drawing attention to the manual labour of obstetrical surgeons, they implied that it surpassed visual perception. The men frequently argued that when called to assist at a gruelling delivery, they performed a manual examination to “see” what was wrong, “discover” the state of labour, “look for” the distressed child, and “observe” its posture.(9)

|

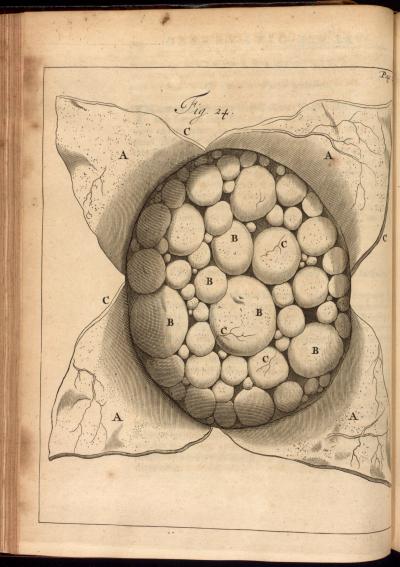

| Close up of a feotus La pratique des accouchemens, by Philippe Peu,1694,Courtesy of the Wellcome Library |

This emphasis on the invisibility of the womb— a womb that could nevertheless be envisioned through touch— might appear to be odds with the images of unborn children that appear regularly in early modern European obstetrical treatises. Looking like playful toddlers, the figures adopt diverse postures as they float in large, oval wombs opened to view. Most early modern images show unborn children in a range of bizarre postures, providing quite a contrast to the normal position. The figures extend their arms toward the mouth of the womb, present their buttocks first, or stretch both their arms and legs toward the cervix. These representations are difficult to comprehend because few authors of obstetrical treatises explained their purpose. The chirurgien accoucheur Philippe Peu argued, however, that though the plates in his book showed only some of the situations of children reduced by twisted umbilical cords, they could serve as ideas for imagining an infinite number of other possible positions.(10) Distinguishing between seeing the images and achieving a perfect understanding of malpresentations, Peu essentially described the images as diagrams.(11) By distilling the scientist’s observations into a simple formula, diagrams provide a principle that can be tested and developed in subsequent research. According to Peu, engravings of unborn children were ideas in visual form that could guide the cerebral activity of practitioners asked to intervene in an unpredictable array of difficult deliveries. Given the sheer diversity of the womb and its contents, the images could scarcely depict what would be found inside the maternal body. Instead, they were modes of interpretation supporting the production of new knowledge.

Illustrations of the unborn were furthermore persuasive, in keeping with the overall contents of obstetrical treatises. They primarily feature malpresentations, cases which medical men claimed as their own specialized domain. Chirurgiens accoucheurs argued that a badly positioned child struggled in vain to exit the womb, while exhausting its mother’s attempts to expel it.(12) According to them, in these unnatural births, the unborn child was dangerously separated from the maternal body, and could not be assisted by the “limited” means of the traditional female midwife. Only the skilled hands and minds of medical men could intervene to save the mother and perhaps the child. Images of the unborn in contorted poses therefore do not represent an autonomous fetus. On the contrary, they portray a vulnerable unborn child at odds with the maternal body, and in desperate need of medical assistance. As visual arguments, the representations picture the moment when men could legitimately enter the lying-in chamber to replace women.(13)

These early modern representations have nevertheless been interpreted as portraying the conquered and knowable female body. According to Kern Paster, the fetuses in English books cover their eyes to suggest the irreducible shame of the womb.(14) Another literary critic, Karen Newman, argues that representations of the unborn child in the womb highlight early modern assumptions about the passivity of the maternal body, and concomitant activity of the autonomous fetus.(15) This analysis is better applied to modern fetal imagery which, as numerous scholars have argued, erases references to the maternal body in order to imply that the fetus is an entirely separate being, endowed with its own set of rights.(16) These images are often used in debates about the status of abortion, with those opposed to legal abortion presenting them as facts documenting the undeniably independent status of the fetus. Thinking historically about pregnancy and childbirth reveals that such claims are rather new; although early modern images of the unborn appear to be similar to modern visualizations, they functioned quite differently.

Medicalization

.jpg) |

| Caesarean Operation, 1601 Scipione Mercurio, Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Maryland |

The increasing practice of caesarean section is a particular target for those who advocate for parturient women, promoting informed consent about risks and alternatives, midwifery services, and the option of home birth. In March of 2010, a New York Times article reported a 32% rate of caesarean birth in the United States, while figures in Canada are only slightly lower.(19) Critics decry these elevated rates for various reasons, including increased health risks for women and high cost. In the past decade, however, some women have begun to demand caesarean sections, a phenomenon popularly known as “too posh to push.” A CBC News article published in 2004, indicated that the rate of these surgeries rose almost three percent between 2002 and 2004, potentially spurred by the wide discussion of celebrities choosing to have caesarean operations in order to avoid the pain of childbirth.(20)

|

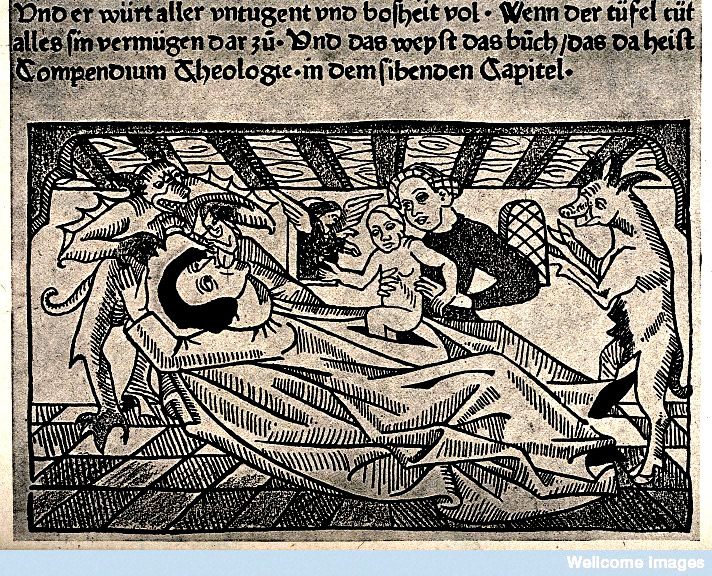

| Birth of the Antichrist Anonymous Woodcut, 1450, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London |

According to the vast majority of authors, a caesarean section should not be contemplated until after the pregnant woman had taken her last breath, in the hopes of baptizing a living child.(24) Before the eighteenth century, most medical practitioners affirmed that the caesarean operation was unnatural and horrifying, part of the reason why it was represented negatively in many visual images. A German woodcut from 1475, for example, portrays a woman lying prone on a bed within a compressed domestic space. Her belly has been crudely slashed open, and a midwife lifts a fully formed child from it. Demonic creatures flank the scene. On the left, a grimacing monster removes the recumbent woman’s soul—depicted as a tiny human figure—from her mouth. On the right, a goatlike animal with swollen teats stands ready to receive and possibly feed the newborn. This violent image represents the birth of the Antichrist, an evil figure whose life story was narrated in opposition to that of Christ during the early modern period. In the New Testament, Christ is born without injuring his mother. She remains a virgin; her body eternally closed. In contrast, the Antichrist brutally ruptures the body of his mother, killing her in the process.

Mortality rates mark an even greater difference between the past and the present, if our focus remains on the western world. In the United States the maternal mortality rate rose from 12 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1980 to 17 in 2008, while in Canada, the rate hovered between 6 and 7 during the same time. Rates fell in poorer countries but remained relatively high; in China, for example, the rate fell from 165 per 100,000 to 40 per 100,000.(25) The rate of maternal mortality during the early modern period was certainly higher than it is today in most of the western world but determining how many women died in childbed has proven difficult because few reliable records survive before the eighteenth century. Some scholars speculate that maternal mortality was higher than fifteen percent of the total births because labouring women were assisted by untrained female midwives working in unhygienic conditions.(26) Yet archival research by such historians as Doreen Evenden, Hilary Marland, and Nina Rattner Gelbart, among others, shows that female midwives in early modern Europe were often literate and capable of handling emergencies.(27) Quantitative research by Irvine Loudon and Roger Schofield indicates that women in Great Britain, continental Europe, and Scandinavia died in childbed at relatively low rates, though many of their records date from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.(28) Adrian Wilson’s study of man-midwifery in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England confirms, however, that only one or two percent of labours were complicated, corresponding with a similarly low rate of maternal mortality.(29) Despite lacking clear evidence for the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it seems that the number of women who died in childbed was lower than we might have presumed throughout the early modern period.

Notes:

1)For more sources related to early modern childbirth see Lianne McTavish, Childbirth and the Display of Authority in Early Modern France (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005).

2)Jacques Guillemeau, De l'Heureux accouchement des femmes (Paris, 1609),

3) Mauquest de La Motte, Traité complet des accouchemens (Paris, 1729; orig. 1721), 49

4)Jacques Duval, Traité des hermaphrodits, parties génitales, accouchemens des femmes (Rouen, 1612), 111.

5)Barbara Duden, Disembodying Women: Perspectives on Pregnancy and the Unborn, trans. Lee Hoinacki (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993). See also Lianne McTavish, ‘The Cultural Production of Pregnancy: Bodies and Embodiment at a New Brunswick Abortion Clinic,’ Topia: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 20, Fall 2008, 23-42.

6)Monica Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

7)Guillemeau, , De l'Heureux accouchement des femmes, unpaginated preface.

8)Pierre Dionis, Traité général des accouchemens (Paris, 1718), 247-8.

9)Philippe Peu, La pratique des accouchemens (Paris, 1694), 408.

10)Peu, La pratique des accouchemens, 441.

11)I thank Steven Turner for suggesting this interpretation to me.

12)Jacques Bury, Le propagatif de l=homme (Paris, 1623), 78-82, and Peu, La pratique des accouchemens, 257-8.

13)McTavish, Childbirth and the Display of Authority in Early Modern France, 173-215.

14) Gail Kern Paster, The Body Embarrassed: Drama and the Disciplines of Shame in Early Modern England (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), 175-78.

15)Karen Newman, Fetal Positions: Individualism, Science, Visuality (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996).

16) Among the many examples see Rosalind Pollack Petchesky, ‘Foetal Images: The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction,’ Michelle Stanworth, ed., Reproductive Technologies: Gender, Motherhood and Medicine (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 57-80.

17) See, for example, Peter Conrad, The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Medical Disorders (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2007).

18) See, for example, Michel Odent, Entering the World: The De-Medicalization of Childbirth (New York: Boyers, 1984).

19)Denise Grady, ‘Caesarean Births are at a High in U. S.,’ New York Times, 23 March 2010 (New York Times.com, accessed 11 August 2010).

20)‘Too Posh to Push?’ CBC News Online (4 March 2004) www.cbc.ca/news/background/csection_births/ (accessed 11 August 2010).

21)Scipione Girolamo Mercurio, La Commare o riccoglitrice (Venice, 1596).

22)Nadia Maria Filippini, ‘The Church, the State and Childbirth: The Midwife in Italy During the Eighteenth Century,” in The Art of Midwifery: Early Modern Midwives in Europe , ed. Hilary Marland (London: Routledge, 1993), 152-75.

23)François Rousset, Traitté nouveau de l’hysterotomotokie, ou enfantement caesarien (Paris, 1581), 16-30.

24) See, for example, François Mauriceau, Des maladies des femmes grosses et accouchées (Paris, 1668), 356-67, Cosme Viardel, Observations sur la pratique des accouchemens naturels, contre nature & monstrueux (Paris, 1671), 172-80, Peu, La pratique des accouchemens, 322-36, Pierre Dionis, Traité général des accouchemens (Paris, 1714), 310-18, and Percivall Willughby, Observations on Midwifery , ed. Henry Blenkinsop (Wakefi eld, UK: S. R. Publishers, 1972), 340.

25) Reuters, ‘WASHINGTODeaths of women in and around childbirth have gone down by an average of 35 percent globally, according to a study using new methods, but are surprisingly high in the United States, Canada and Norway,’ (12 April 2010). www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE63B4MG20100412 (accessed 11 August 2010).

26) Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, The Art and Ritual of Childbirth in Renaissance Italy(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 25, uses evidence supplied by David Herlihy and Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, Tuscans and their Families: A Study of the Florentine Catasto of 1427 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 277.

27) Doreen Evenden, The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), Hilary Marland, trans. and ed., ‘Mother and Child Were Saved’. The Memoirs (1693–1740) of the Frisian Midwife Catharina Schrader (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1987), Hilary Marland, ‘Stately and Dignified, Kindly and God-fearing: Midwives, Age and Status in the Netherlands in the Eighteenth Century,’ in The Task of Healing: Medicine, Religion and Gender in England and the Netherlands 1450–1800 , ed. Hilary Marland and Margaret Pelling (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Erasmus Publishing, 1996), 271-305, and Nina Rattner Gelbart, The King’s Midwife: A History and Mystery of Madame du Coudray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

28) Irvine Loudon, Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality 1800–1950 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1992), Roger Schofield, ‘Did the Mothers Really Die? Three Centuries of Maternal Mortality in the World We Have Lost,’ in The World We Have Gained , ed. Lloyd Bonfi eld, R. M. Smith, K. Wrightson, and P. Laslett (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), 231-60.

29) Adrian Wilson, The Making of Man-Midwifery: Childbirth in England 1660–1770 (London: UCL Press, 1995), 15-19.