From R. James' A Medical Dictionary, Remi Parr, 1743, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

Early Modern Illnesses and Treatments

Surgeries, Deformities and Disease

|

| Cutting for the Stone From R. James' A Medical Dictionary, Remi Parr, 1743, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library |

Cutting for the Stone

By Jacob Rodriguez

On Stones: Surgical Removal of Bladder Stones in the Early Modern Period

In the 1583 publication On Monsters and Marvels, the famous royal surgeon and author Ambroise Paré described the event of the extraction of bladder stones from a Parisian named Pierre Cocquin. According to Paré’s account, brothers by the name of Callos performed the operation, which consisted of the removal of a stone “as thick as a walnut” from Cocquin’s body(1) . It isn’t surprising that Paré commented on the success of the operation, noting that Pierre Cocquin was “still living [in Paris] at the present writing,” considering that the procedure known as ‘cutting for the stone’ often resulted in the death of the person undergoing surgery. Unlike the modern surgical methods used in the treatment of bladder stones, which occur as a result of the formation of dissolved urinary minerals into solid masses, ‘cutting for the stone’ in the early modern period was an extremely invasive and morbid procedure.

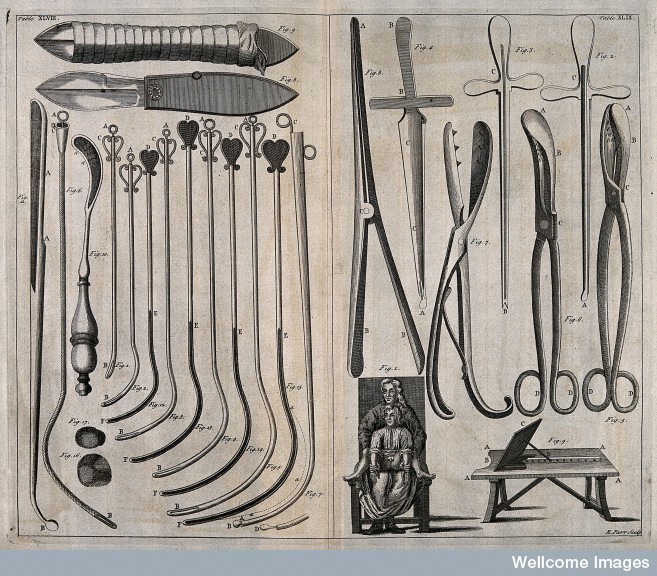

The image to the right, an engraving by Remi Parr from Robert James’ 1743 Medical Dictionary, illustrates the medical tools used for the removal of bladder stones. The arrangement and large scale representation of the scalpels, catheters and forceps around the smaller, ancillary image of a young man being prepared for the operation by the surgeon visually allude to the intrusive nature of the procedure for the removal of bladder stones in the early modern period. The large instruments menacingly encroach into the cramped area of the image reserved for the depiction of a figure whose unflattering pose (he is naked from the waist down and his legs are forcefully spread apart) leaves his body vulnerable to the tools that surround him as well as to the viewer’s gaze. Additionally, the variety and quantity of surgical instruments displayed in the image point to the development of the medical procedure of cutting for the stone from ancient to early modern times. During the Greco-Roman period, the practice for the removal of bladder stones, called lithotomy after the Greek word for stone- litho, involved only a knife and hook as the primary tools for the operation. However, by the sixteenth century, new methods that had developed for cutting for the stone required more and different types of instruments. Harry W. Herr, a current professor in the Department of Urology at Cornell Medical College, explains the procedure known as the Marian operation, named after the surgeon Mariano, a student of Francisco Romano, who popularized this method for cutting for the stone in the mid-sixteenth century:

“The patient was placed on his back on a table. His legs were bent at the hips and knees flexed so they were almost touching his chest, thus the perineum was brought into a nearly horizontal position. For the first time, a grooved sound was passed along the urethra to guide subsequent instruments into the bladder. A vertical incision was made in the median raphe’ and cut down into the bulbous urethra on the staff. A gorget was passed along the groove used to guide two conductors, female and male, which were separated to open the wound. A Paré’s dilator was inserted guided by the button and then forceps of either the duck-bill or crow’s beak type. The dilator tore through the prostate and bladder neck. Forceps with two or more blades were passed into the bladder to grasp and crush the stone; fragments were removed with a scoop.”(2)

In the early-modern period, a person who elected to undergo such a racking and rigorous procedure did so without the comfort of any local or general anesthetic that modern patients receive during surgical treatment for removal of bladder stones. Thus, it goes without saying that the Marian operation was an excruciating experience. Ambroise Paré even recommended to fellow surgeons in his manual on cutting for the stone, “On Stones,” that “it is necessary to have four strong men, not fearful or timid, that is, two to hold [the client’s] arms, and two others who will hold a knee with one hand, and with the other the foot,” in order to restrain the person being operated on from writhing their body in reaction to the pain of the incision (3). In one account of the removal of bladder stones from 1612, the physcian, G. Du Vouldy, described the harrowing physical suffering expressed by someone undergoing the procedure:

“the sick person’s face was drenched in tears, his body in sweat and blood, his eyes were half dead and his tongue black, his lips heavy from the fervor of the cries that he tore from his mouth.”(4)

Despite the prospect of such an operation, many who suffered from bladder stones were willing to endure such a painful procedure, one whose risks included and often resulted in death, in order to relieve the constant agony of their condition.(5)

Cutting for the Stone: A Risky Business

The high mortality rate associated with cutting for the stone in the early modern period made this method for treating bladder stones a dangerous one, not only for those undergoing the operation, but also for the surgeons who performed this type of invasive procedure. In fact, the original Greek translation of the Hippocratic Oath specifically prohibited medical physicians from performing the operation: “I will not cut for stone, even for patients in whom the disease is manifest; I will leave this operation to be performed by practitioners, specialists in this art.”(6) Even from early medical history, the practice of cutting for the stone was risky business, and for good reason.

|

| Bladder Stones From Ambroise Pare's On Monsters and Marvels, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library |

For many physicians and surgeons in the early modern period, reputation was based primarily on the success or failure of curing those who suffered from illness. Educated physicians were reluctant to offer surgical treatment to those inflicted with bladder stones for two reasons: 1) surgery was considered an inferior medical practice whose practitioners neither required a knowledge of Latin nor formal training in the University; and 2) since even in the best of cases those who survived the initial operation often suffered and died from complications of cutting for the stone. However, because the procedure was considered to be so deadly, surgeons who managed to successfully administer the operation achieved a significant degree of fame and prestige. For instance, the Callos brothers, about whom Paré writes in his text, received special invitations from distinguished and noble figures, including the Duchess of Ferrara, to practice cutting for the stone in their cities and territories. The two brothers’ expertise in cutting for the stone was remarkable enough that the stones they removed from their patients’ bodies acquired an almost venerated status. Paré included images of stones extracted by the Callos brothers in his text (fig. 2) and boasted that the two surgeons presented these specimens to the King of France and himself as gifts “to be put in [their] cabinet.”(7) The images of the stones in Paré’s text, as well as the actual objects they represented, stood as visual and material metonyms of the Callos brothers’ surgical skill. The success of the Callos brothers in treating those inflicted with bladder stones elevated them to the status of medical celebrities and transformed the stones they extracted- the physical manifestations of their medical abilities- from pain causing objects of bodily waste to ones of natural wonder.

While the Callos brothers’ success reaped professional rewards, the consequences for surgeons who performed unsuccessful operations were severe. The seventeenth-century ecclesiastic and self-trained surgeon Jacques Beaulieu (1651-1714)- the protagonist of the famous French nursery rhyme “Frère Jacques-” made his entry onto the Parisian medical scene by claiming expertise in the area of cutting for the stone. However, it was soon discovered that the monk was laboring under false pretenses when close to half of those he treated died from complications related to surgery; according to Harold Ellis, a historian of medicine, during a year when Beaulieu cut 60 people suffering from bladder stones, less than 30 survived the initial operation.(8) Although Frère Jacques tried to exonerate himself by accusing his fellow monks of having poisoned those who died, the people of Paris chased Beaulieu out of the French capital as a charlatan, or unskilled practitioner. It wasn’t uncommon for surgeons to live a nomadic existence, moving from one city to the next when their reputation became compromised by the failure of their curative practices.

Travel and Alternative Treatments

Today, it’s common for patients seeking the best medical care to travel long distances to receive treatment, particularly when the patient’s medical condition risks being fatal. Many patients who have the monetary means jockey for the opportunity to be treated by doctors and surgeons who have gained reputations as the top practitioners in their respective fields without regard to the physicians’ proximity to their homes. For example, during the recent health care debate in the United States, the lobbying group, Patients United, famously released a television ad in which a Canadian, Shona Holmes, recounts her experience of traveling to the US to receive treatment for her brain tumor because, as she claims, she didn’t have access to immediate medical care for her condition in Canada.

The issue regarding access to medical treatment is also an important political concern in Canada. Lianne McTavish, a professor at the University of Alberta, has recently written about the effects on and experiences of women seeking abortion services in New Brunswick. The provincial government in New Brunswick has enacted policies that make it difficult for women to receive subsidies for abortions, such as requiring the written consent of both a doctor and a gynecologist in order to undergo the procedure, ultimately restricting a woman’s access to an essential component of reproductive services in violation of the mandates of the Canada Health Act, passed in 1984.(9) As a result of these policies, women in New Brunswick can’t rely on hospitals for abortion services, and, instead, they’re forced to travel to abortion clinics, like the Morgentaler Clinic in Fredericton, to receive the treatment they require.(10)

The need to travel for essential medical care or to seek out the most reputable medical specialists for rare or deadly illnesses is not a modern phenomenon. In the early modern period, when the stakes of medical care were high, those who were sick and financially able wanted the best available treatment administered by the best-trained medical practitioners.

As evidenced by the careers of the Callos brothers, the fame and prestige of successful surgeons wasn’t locally confined. News of famous physicians spread, as well as cities that built reputations for specializing in certain types of treatments. In the seventeenth-century (except, perhaps, during the medical tenure of Jacques Beaulieu), Europeans in the medical community considered Paris a city whose surgeons were particularly able in cutting for the stone; so much so, that in 1636, Sir Francis Crane, an English physician and member of the Order of the Garder, traveled to Paris to receive treatment for bladder stones. As a physician himself, we must suspect that Sir Francis Crane had reason to believe that surgeons who practiced cutting for the stone in Paris had more specialty and expertise than those in his home of London; otherwise, it seems odd that Sir Francis would risk making the uncomfortable trip across the Channel in such a painful condition if equally good treatment were thought to be available in closer proximity. From an account given by his companion, Lord Scudamore, we know that Sir Francis Crane survived the operation and removal of a stone “almost as big as an ordinary hen’s egg and of that shape.”(11) However, like many who were operated on for removal of bladder stones, Sir Francis Crane lived only a short time after the procedure.

Since even those who received treatment from surgeons believed to be the best trained often died, it’s not surprising that people suffering from bladder stones sought curative alternatives to surgical treatment. The proscription of non-surgical treatments (although probably less effective) would have been beneficial to both the physician and the person seeking treatment; the physician (most likely) risked no chance of killing those to whom he offered medical care and the sick person risked no chance of dying from treatment! One example of an alternative to cutting for the stone offered by doctors to those suffering from bladder stones in the early modern period required adherence to a strict diet. In a letter written in 1637, the Scottish physician living in Paris, Dr. William Davidson, gives instructions to a suffering client:

“First yow sal endevoir above althings to hold your belly lousse, that is ane endemical or populair secknes to all our Scottes, and thair is nothing more meit ather to engender or to augment ane once engenderet stone then hardnes in the belly, thairfore yow schall observe the cours following: Abstein from spycereye, spysset meattes, saltet meattes, venaisson, dryet fishe, new ayll or beir, all suche qhilk I know yow r sufficiently instructed of alredy, having bein indisposet since a long time.”(12)

The logic of the dietary proscription seems clear: in order to prevent the formation of hard stones, one should refrain from consuming those types of food thought to keep the stomach (“belly”) from being “lousse.” Ambroise Paré explains the reasoning behind dietary cures for and prevention against bladder stones: “As for the diet, it is necessary to avoid fish, meat of beef, or pork, river birds, vegetables, cheeses, milk products, fried and hard eggs, rice, pastries, unleavened bread, and generally all other food which make obstruction.”(13) In short, Paré’s instructions are meant to aid one in “avoiding the causes of the gross and viscid humors.”(14) In the early modern period, it was believed that one’s health depended on the regulation and balance of the body’s four humours: blood, phlegm, and yellow and black bile. Barbara Duden’s study of female patients from the German town of Eisenach in the late 18th century shows how people in the early modern period understood the body as open and permeable to its surrounding conditions.(15) It was believed that when the body’s “openness” was obstructed, as in the case of someone suffering from bladder stones that restrict the normal flow of urinary fluid from exiting the body, the hurmours were prevented from naturally regulating their equilibrium, and the body would experience illness. While it may sound ludicrous to our modern ears and conflict with modern understandings of the body, the simplicity of Dr. Davidson’s reasoning would have made perfect sense in the early modern period: hard and tight should be remedied with soft and “lousse” in order to encourage the natural flow of hurmoural fluids and counteract the buildup of hard material in the body.

The French essayist, Michel de Montaigne, is probably the most famous Renaissance figure to have suffered from bladder stones. Like Dr. Davidson’s correspondent, Montaigne also sought alternatives to surgical treatment for his condition. Famously, Montaigne traveled through Europe in search of curative baths to treat his stones. The historian, Georges Vigarello, mentions in his book, Concepts of Cleanliness: Changing Attitudes in France since the Middle Ages, that “in certain cases…sixteenth-century bathers confidently expected an amelioration of their diseases. A bath of warm thermal water, like a bath in ‘ordinary’ water, could, for example, dissolve stone…”(16) Whether or not the baths alleviated Montaigne’s pain is uncertain; however, his travels in search for relieving waters shaped the experience of his later life. Who knows what revisions made to Montaigne’s famous Essaies resulted from his curative journey? Montaigne doesn’t shy away from communicating his physical suffering to his readers. Throughout the Essaies, Montaigne constantly makes reference to his weakness; from the start, in his introduction, Montaigne declares that his “powers [as a writer] are inadequate” and warns that his “defects will here be read to the life…”(17) Montaigne’s criticisms are not purely literary since he explicitly links his body to his text: “I am myself the matter of my book…”(18) For Montaigne, the body served as the most important means of understanding the world:

“The senses act as the proper and primary judges for us, and they perceive things only by their external accidents; thus it is no wonder that in all the functions that serve the welfare of society there is always such a universal admixture of ceremony and outward show that the best and most effective part of a government consists in these externals. It is still man we are dealing with, and it is a wonder how physical (corporelle) his nature is.”(19)

According to Montaigne, knowledge is communicated through the body, the primary receptor and interpreter of sensory data, via quintessentially physical means. Montaigne’s experience of his body- a body which suffered the pains of bladder stones- shaped his perception of the world.

Notes:

1)Ambroise Paré, On Monsters and Marvels, translated by Janis L. Pallister (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 49

2) Harry W. Herr, “Cutting for the Stone: the Ancient Art of Lithotomy,” BJUI Journal No. 101 (2008): 1215

3) Ambrois Paré, Ten Books of Surgery with The Magazine of the Instruments Necessary for It, translated by Robert White Linker and Nathan Womack, (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1969), 193

4) G. Du Vouldy, Discours des accidens arrivez à Monsieur F. Conseiller du Roy en ses conseils d’Estat & privé en l’éxtraction de deux pierres faicte en l’année mil six cens douze, (Paris: Pierre Recollet, 1614), 16 (Translations are mine)

5) In Chapter 4 of “On Stones,” “On the Prognosis of Stones,” Pare comments, “Those who have the stone in the kidneys or in the bladder are in almost continual pain,” p.179

6)Quoted in Herr, p. 1214 from F. Adams, The Genuine Works of Hippocrates Translated from the Greek, (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1938)

7)Paré, On Monsters and Marvels, p. 52

8)Harold Ellis, A History of Bladder Stone, (Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1969), 15

9)Lianne McTavish, “The Cultrual Production of Pregnance: Bodies and Embodiment at a New Brunswick Abortion Clinic,” Topia v. 20 (Fall 2008): 26

10)McTavish, p. 27

11) Laurence Martin, “Sir Francis Crane KT. And Dr. William Davison; Patient and Doctor in Paris in 1636,” Medical History No. 23 (1979): 348

12) Willian Davidson, “Advice for Stone in the Bladder” (1637)

13) Paré, Ten Books on Surgery, p. 181

14) Ibid. p. 181

15) Barbara Duden, The Woman Beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991)

16) Georges Vigarello, Concepts of Cleanliness: Changing Attitudes in France Since the Middle Ages, translated by Jean Birrell, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1988), 10

17) Michele Montaigne, The Complete Essays, translated by Donald Frame, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1965), 2

18) Ibid

19)Montaigne, p. 710