The worldwide ritual of ringing a bell at the end of radiation or chemotherapy treatments has a positive impact on the transition to post-treatment life for cancer patients and their caregivers, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Alberta.

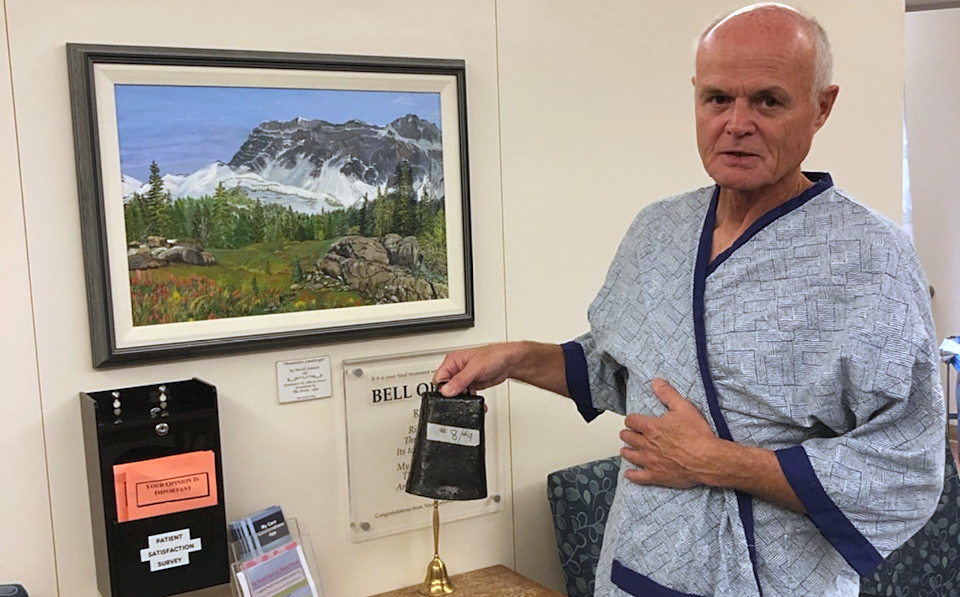

"I think the bell really helped me get through my radiation treatment," said study participant Adam Hardwicke-Brown, 66, who went through treatment for tongue cancer. "It gave me inspiration and hope that things were going to get better."

In a paper published in the Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, the researchers found that the ritual created a sense of community among cancer patients, helped them mark an important milestone, and gave them a sense of self-determination as they finished treatment.

"A cancer diagnosis is like going on a journey where you have no idea where you are going and no control over where your life will be," said Edith Pituskin, associate professor of nursing and clinical oncology and Canada Research Chair in Chronicity.

"We think that ringing the bell might give patients and their families a small bit of control in an uncontrollable environment."

The bell ringing ritual started at the MD Anderson Cancer Centre in Texas in 1996, and has since spread to cancer centres around the world. A patient who completes chemo or radiation treatments rings the bell and staff and other patients cheer and take photos. There is a bell for patients at each of the three chemotherapy units and half a dozen radiation units within Edmonton's Cross Cancer Institute.

Pituskin pointed out that ringing the bell is not part of the formal treatment plan, but rather a patient-led practice, which means it has not been given much academic attention.

"The bells are placed in the treatment areas," she said. "It's up to somebody if they wish to ring it or not, quite independent of the treatment team. Whether they do or not is not known, nor how people feel about the bells and their individual experiences."

Nursing student Abigail Bridarolli, Jude Spiers, an associate professor in the Faculty of Nursing, and Pituskin did extensive interviews with two couples in which one spouse had cancer and the other was their primary caregiver, and then identified themes from their responses.

Hardwicke-Brown had a 14-hour surgery to remove 40 per cent of his tongue and then reconstruct it using tissue from his forearm. That was followed by 30 radiation treatments which caused excruciating mouth pain.

"You can't eat, you can't swallow, you can't talk, your weight drops," Hardwicke-Brown said. "I wanted to quit.

"But pretty much every time I would go, I would hear someone ringing that bell. It was like a beacon of hope for me. It really helped me get through, knowing my turn would come."

Hardwicke-Brown's wife, Colleen Norris, a professor in the Faculty of Nursing, said the bell encouraged her too, as she attended every radiation treatment with her husband. She knew that once he rang the bell, his recovery would not be complete-he would have to continue with speech therapy, physiotherapy, nutrition counselling, even lessons on how to swallow again.

"But it moved him along to know that at least he was able to get through those 30 radiation sessions," she said. "And everything was in place for him to keep going on whatever this journey entailed.

"It still brings tears to my eyes."

Five years later, Hardwicke-Brown feels fortunate to have survived his cancer diagnosis and treatment. He visits his oncologist every three months for check-ups, and helps others as founding director of the Head and Neck Cancer Support Society and a patient adviser to Alberta Health Services.

Pituskin, who is also a member of the Cancer Research Institute of Northern Alberta, said that cancer care has advanced over the past 25 years to the point where many cancers are now treated like chronic illness, meaning many patients may never "finish" their treatment, and thus never have a chance to ring the bell.

She said more research should be done to learn how such rituals affect those people, but she noted that she first became interested in the topic while her own father was undergoing treatment for lung cancer. He died before he was able to get any pain relief from his course of radiation, but told her that watching other patients ring the bell to mark the end of their treatments was important to him.

"For him the ringing of the bell meant hope and hope meant freedom from pain," said Pituskin. "That opened my eyes to the fact that the bell has different meanings for different patients.

"For my dad, the meaning was still there and the hope was still there."