Whether it’s inspired by Jurassic Park, The Land Before Time or documentaries like the seminal BBC series Walking with Dinosaurs, it seems like every kid passes through a phase of wanting to be a paleontologist. Consuming dinosaur-themed media when you’re a child is like being let in on a wonderful secret; a whole world of monsters that actually existed. Monsters that you’re allowed to believe in. I was one of those kids. Dinosaur magazines, movies, trading cards, games—even duvet covers. The only difference for me is I never grew out of it.

Some context, first, on the prospects of a dinosaur-obsessed kid from Belfast in the late ‘90s actually growing up to become a palaeontologist. Only two dinosaur fossils have ever been found throughout the whole of Ireland: fragments of a Scelidosaurus and a Megalosaurus (both, as chance would have it, in my home county of Antrim). The main problem, generally, for any aspiring dinosaur palaeontologists back home is that during the time period that we find dinosaur fossils from, in nearby places like Scotland and England, Ireland was underwater, drowned by high global sea levels.

As I write this, there is a greater dinosaur fossil assemblage on my desk (small claws and teeth I use to teach undergraduate students about microsites), than has ever been collected in the entirety of Ireland. This doesn’t mean that a career in palaeontology is impossible (obviously, or I wouldn’t be writing this), but it does mean that you have to get creative and be willing to travel.

My “way in” came through an undergraduate degree in archaeology at Queen’s University Belfast. My reasoning was simple and two-fold: both subjects required you to dig holes, and humans and dinosaurs both have bones. Afterwards, I was exceptionally lucky to receive a Canadian Memorial Foundation Scholarship, which allowed me to come to Edmonton in 2012 to study towards a master's of science in the Faculty of Science under Dr. Philip Currie. You’ve probably heard of Phil, even if you haven’t realized it. He worked on some of the first feathered dinosaurs, found the world’s first complete baby horned dinosaur, and was one of three scientists used as a model for Sam Neil’s character in Jurassic Park, Dr. Alan Grant.

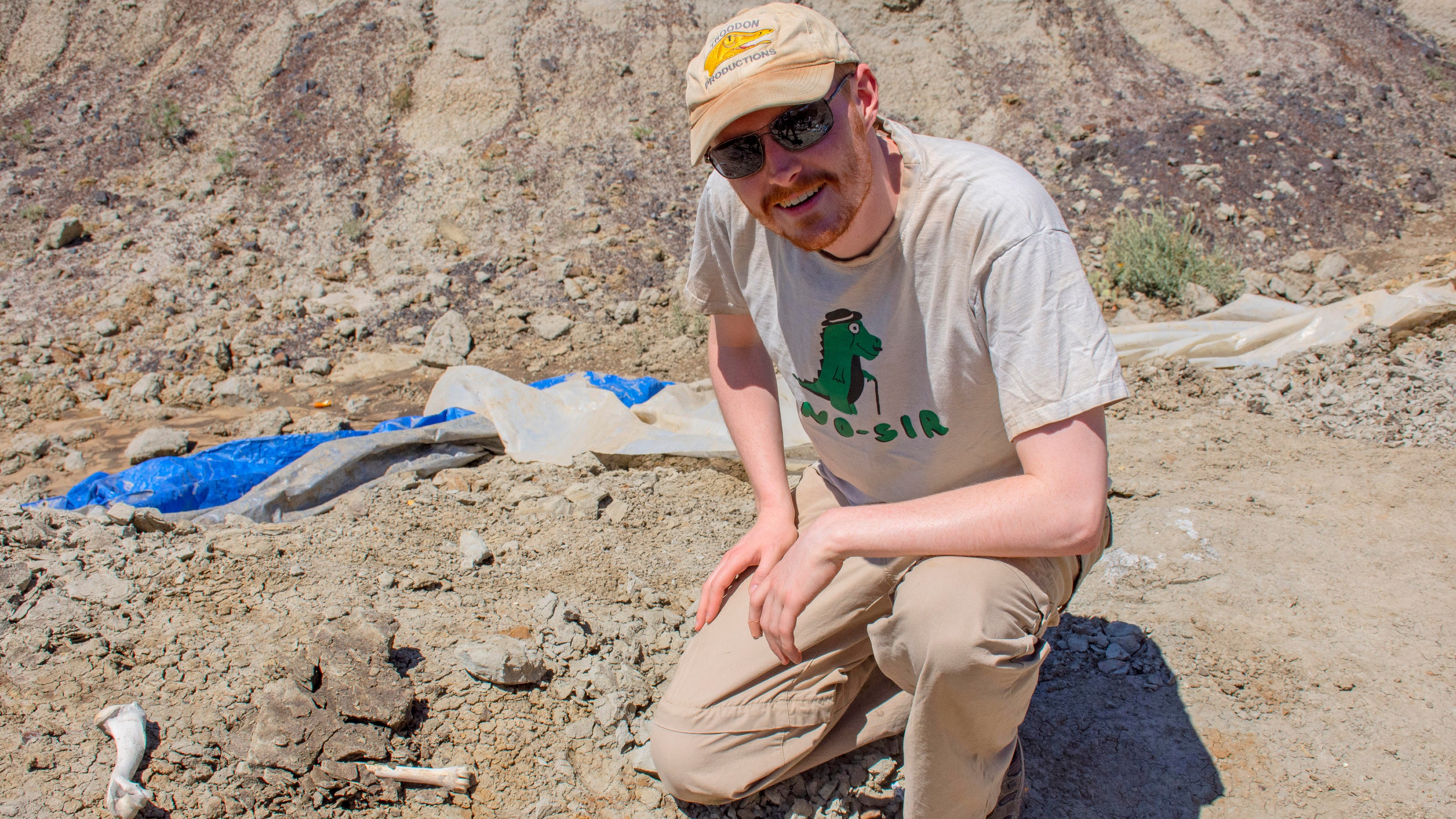

The learning curve was much steeper than my “bones and digging” logic had prepared me for. During my first week of fieldwork in the badlands of Dinosaur Provincial Park in southern Alberta, I excitedly brought what I thought was a dinosaur kneecap (or patella) to Phil for inspection. To my bemusement at the time, he just chuckled and shook his head. What I know now, of course, is that dinosaurs don’t actually have patellae, and I had just presented my new supervisor with a not even particularly interesting rock.

Grad school is the slow process of becoming an expert in your subject while also trying to make yourself employable. By the end of it I had published research on tyrannosaur dinosaurs, presented at international conferences and amassed many stories from fieldwork. Ultimately, though, what I fell in love with during my time in the Currie Lab was teaching and outreach. The feeling of uncovering a fossil that nothing has laid eyes on for 72 million years is incredible, but for me, it’s not as good as the feeling of putting that fossil into a student’s hands and watching their face light up.

Today, I teach the introductory dinosaur palaeontology classes for the university and run the Faculty of Science massive open online courses (MOOCs) like Dino 101, which has been taken by hundreds of thousands of people worldwide (including my mum back in Ireland). Often, I’m one of the first science instructors a student encounters, and in many ways — thinking back to that rock in Dinosaur Provincial Park — it’s the perfect role for me. I’m nothing if not enthusiastic!

Writing is something I picked up as a teenager, and found solace in throughout emmigration and grad school. In mid-March (just before St. Patrick’s Day, as fate would have it), my first book of poetry, Separation Anxiety, was published by University of Alberta Press. Separation Anxiety follows the deterioration of a long-term relationship, interweaving poems dealing with the loneliness of immigration and the anxiety of separation from home. The idea was to explore the emotional toll of different kinds of separation and loss, but to do so without losing a sense of hope that things can get better. I think it’s a book that a lot of people can relate to. Whether you’re part of an immigrant community or not, separation is something we all go through at different times in our lives.

While I still have a healthy dose of imposter syndrome, having never studied English or creative writing at university, the subject matter is something I very much feel like an expert in. And I am at least beginning to feel as if I know the bones of poetry. Or at least, of the poetry that I write.

About Gavin

Gavin Bradley is the U of A Science MOOC Coordinator and assistant lecturer in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences in the Faculty of Science. He is also a paleontologist, and award-winning writer from Belfast, Northern Ireland, currently living in Edmonton, on Treaty 6 territory. His work has appeared in The Irish Times, The North, Best New British and Irish Poets and Glass Buffalo. His debut poetry collection, Separation Anxiety, is available from your local independent bookstore as well as online.