Safe drinking water comes at a price, but the alternative is far more costly

[Editor's Note: Article was accurate at time of original publication in the Spring 2007 issue of New Trail.]

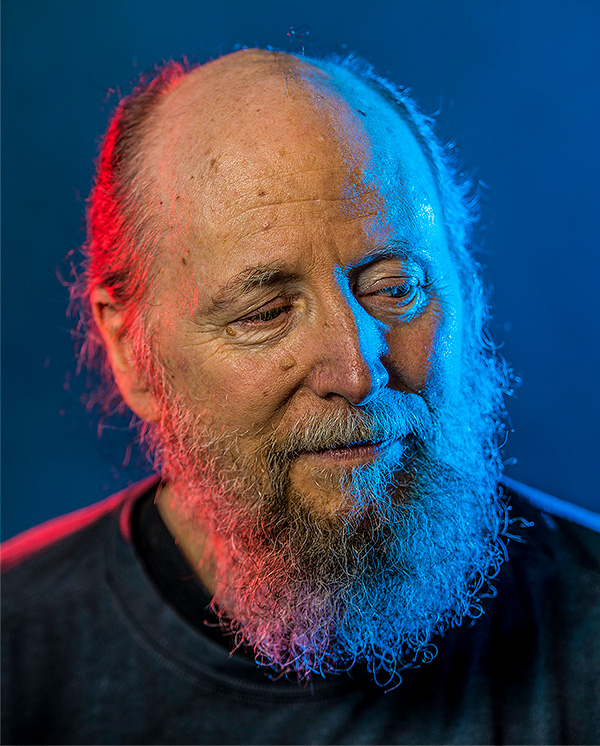

Steve Hrudey, '70 BSc, has been involved with drinking water safety and other environmental contamination issues for a long time. He currently carries the long-winded title of U of A professor of environmental health sciences and associate dean in the U of A's new (2006) School of Public Health, Canada's first faculty devoted to this issue. In addition, he's an honorary professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

He has recently been elected a Fellow of the Academy of Sciences of the Royal Society of Canada (2006) and became the first non-lawyer to be appointed by cabinet as chair of the Alberta Environmental Appeals Board (2005), a quasi-judicial tribunal reporting to the minister of environment. Previously, he has served in several prominent roles concerning water, including the first leader of the protecting public health program of the Canadian Water Network and chair of the NATO priority panel on environmental security in Brussels, Belgium. And he's won his share of other awards and accolades - including an honorary degree in environmental health sciences and technology from the University of London for his career publications that include over 200 scientific and technical articles relating to environmental risk assessment, safe drinking water, and waste management. He's also published five books, including the 2004 tome (around 500 pages) he co-authored with his wife, Elizabeth, titled Safe Drinking Water: Lessons from Recent Outbreaks in Affluent Nations

So you'd think when it comes to water contamination issues, nothing would faze him. Think again.

"I was frankly shocked at what I encountered when I became involved in the Walkerton Inquiry," says Hrudey. "Ontario is sort of the big brother in Confederation and the most developed place in Canada, yet a common attitude was to horrendously undervalue water.

"If you want to have safe drinking water you have to treat it. That costs money and somebody has to pay for that. I think that reluctance to face up to the cost of clean water certainly underlay what occurred in Walkerton.

"Ontario has invested an awful lot and passed new regulations since the tragedy, but the mindset amongst many people still is 'water should be free; it's a human right.' Well, there are lots of things that are human rights, but if you want to deliver something that requires technology, somebody has to pay for it."

He's talking, of course, about the tainted water scandal in Walkerton, Ontario, where in May 2000 E. coli O157:H7 bacteria, a pathogenic strain of the common E. coli found in huge numbers in the gut of all warm-blooded animals, contaminated the town's water supply, killed seven people and sickened more than 2,000. Hrudey served on the research advisory panel to the Walkerton Inquiry led by commissioner Justice Dennis O'Connor set up to look into what happened and how it could be prevented from happening in the future.

The media focus was on two brothers - Stan and Frank Koebel - who ran the town's water system but who had no formal training as water treatment operators. They allowed one of the town's wells to operate after rainwater mixed with cow manure tainted the water supply with the pathogenic E. coli bacteria, and then falsified data to cover up their failure to do tests that would have revealed the contamination.

"One of the things after Walkerton that's distressing is that I hear from people who should know better, 'Oh, that was just a couple of drunks.' Just kind of dismissing it like there wasn't a bigger problem to be dealt with. Anyone who's even perused the final Inquiry report will find that there's no way Justice O'Connor pins what happened strictly on the Koebel brothers. Sure, they did lots of bad things and competent people in their shoes could have prevented it, but the circumstances in Ontario that allowed disaster to happen were the bigger problem.

"When you talk to people who were on the ground in Ontario when it happened," Hrudey continues, "they'll tell you that it was just bad luck for Walkerton. It wasn't like they were a unique situation. Very few places in these smaller communities in Ontario were paying enough attention to drinking water at that time. They're paying a lot more attention now because of all the new regulations. But are they doing a better job? That's not quite as certain."

Could what happened in Walkerton happen here in Edmonton? Well, it sort of already has. In the winter of 1981-82, Banff was hit by an outbreak of giardiasis, more commonly known as beaver-fever. The following winter was Edmonton's turn and by the time it was over there were 895 lab-confirmed cases of giardiasis in Edmonton, which made it the second largest reported outbreak of waterborne giardiasis in the developed world. "And that's only the confirmed cases," Hrudey says. "You take into account people who got sick but didn't get tested by a lab and the number jumps to around 9,000 people who probably got sick from drinking Edmonton tap water.

"Edmonton has an interesting water history and that's largely how I got into the drinking water business. I was born and raised here and got used to the fact that every spring the water smelled liked gasoline. It was pretty putrid stuff, but it was just a rite of spring - the snow melted and the water tasted rotten."

"Canadians hear that we have 20 or 25 percent of the world's fresh water supply, so we think it's basically free and that we don't have to worry about it because we have so much. But when it comes to safe drinking water, no matter how pure the source may look - water as it's found in the environment isn't safe to drink."

It wasn't until Hrudey got involved with the University and water quality issues - first in Civil Engineering in the environmental engineering program - that he found out why the water in spring had tasted so bad for all those years.

"We were getting our water from the Rossdale water treatment plant in the city centre and its intake was affected by numerous storm sewer outfalls upstream," says Hrudey. "So every spring when the winter crud on the streets melted it all went into the river, and that's the source water you had to start with when treating it to make drinking water."

In February 1985 another problem arose - people woke up to a newspaper headline blazing the news of "Carcinogens Found in Edmonton's Drinking Water" during a runoff episode.

Laurence Decore, '61 BA, '64 LLB, '99 LLD (Honorary), Edmonton's mayor at the time, was convinced that action on the city's water was imperative. So Hrudey was brought on board by the city's new manager of water plants, Allan Davies, and the Edmonton Board of Health and Alberta Environment, to head up an independent inquiry into Edmonton's water. "Frankly," Hrudey says, "our water system had not been very well managed at that time.

"Yes, we had multi-million dollar water treatment plants that a lot of places in Canada still really haven't invested in. But they had been allowed to be run very poorly and given the challenges that we faced - water quality in the North Saskatchewan can go from excellent to crummy overnight - the treatment plants just weren't up to handling the task.

"Now with Epcor managing the water we probably have one of the best water facilities in North America, if not the world. I attribute that to ultimately learning from our mistakes. But that's not the case everywhere. Some places seem to be pretty slow in learning from their mistakes.

"In Alberta, the water treatment systems are probably some of the best in Canada. Most of the major cities have good water treatment facilities and there's a high level of training and expertise. Where you worry is in the really small locations, towns of a few hundred people. But I think the biggest problem in Canada concerning water is that we take it for granted.

"Canadians hear that we have 20 or 25 percent - depending on who you listen to - of the world's fresh water supply, so we think it's basically free and that we don't have to worry about it because we have so much. But when it comes to safe drinking water that view is a terrible mistake to make because - no matter how pure the source may look - water as it's found in the environment isn't safe to drink. The cause of waterborne disease is pathogens found in the fecal waste of warm-blooded animals. Tell me a place on this planet where there's never been a warm-blooded animal. Even if you're up on a glacier you don't know who's been walking above you. And if people haven't, birds have."

To make it as certain as possible that water is potable and pathogen-free requires that a multi-barrier system be maintained between the possible contamination and what people drink. The barriers start with protecting the source water before moving on to utilizing all the necessary treatment technologies to purify the water, and then consistently monitoring the process to make sure things are working as they're designed to.

Here in Edmonton the treatment process begins by running the water through a coagulation-sedimentation-filtration system followed by chlorination and UV treatment. What you don't want to do is put all your eggs in one basket... like they have in Vancouver.

"We recently saw three million people in Vancouver on a boil water advisory for a couple of weeks because they haven't invested in proper water treatment," Hrudey says. "Vancouver relies on what are called 'protected' catchments and they only chlorinate or ozonate the water distributed from reservoirs collecting from these 'protected' watersheds. But that didn't protect them from the post-storm turbidity problem they had in November [2006]. I was out there then and you couldn't see clearly through a glass of water.

"If you do a survey on water rates you'll find that we pay more for our water than a lot of other places do, but we're getting something for it. Other places, like Vancouver, said they weren't going to invest in a water treatment plant (one is finally under construction) and they'd take their chances with the weather, and it finally caught up with them. So the water rates in Vancouver are likely lower than they are in Edmonton. But do you want to be on a boil water advisory?

"In 1995, Victoria also had an outbreak of toxoplasmosis caused by the protozoan pathogen Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that poses a risk to newborn babies. It was the kind of thing where chlorination alone wasn't enough to protect the public and I don't know that anything has improved since that outbreak. In this case, chlorination is only one component of the required multiple barrier system."

"Currently, there are still millions of people dying around the world every year for lack of safe drinking water and adequate chlorination would probably prevent most of those deaths."

Chlorination is primarily effective for bacteria and viruses. It can also be effective with some protozoan pathogens, but for Cryptosporidium, which has become a common pathogen - the cause of the 2001 North Battleford, Saskatchewan, outbreak that infected more than 7,000 people - chlorination is not sufficient. In North Battleford, the city's drinking water intake was about three kilometres downstream from its sewage outfall and when the treatment process was allowed to deteriorate and chlorination was all that remained, they had an outbreak of cryptosporidiosis because that barrier was not adequate for Cryptosporidium.

Epcor recently installed an ultraviolet light (UV) treatment system in part because there was an incident here in Edmonton in 1997 where Cryptosporidium got into the treated water. "Normally you rely on filtration to remove fine particles because pathogens are also fine particles," says Hrudey. "But it's difficult when the source water quality is changing the way it does in the river to maintain the performance up to the 99.99 plus percent rate that's needed to adequately remove the fine particles, so you need an additional disinfection step. That's why UV was adopted in addition to chlorination, so we're now thoroughly protected against Cryptosporidium and other pathogens."

And despite no hard evidence that chlorination by-products can be harmful to human health - and plenty of examples of how not chlorinating can lead to outbreaks of waterborne diseases - some communities are still reluctant to use this effective microbial barrier. In his most recent book, Hrudey points to the English village of Bramham where chlorine use was minimized following residents' complaints about the taste of their water and, as a result, 3,000 people became infected with gastroenteritis. Closer to home, residents of Erickson, B.C., resisted chlorine treatment of their water by blockading the road to their water supply for 55 days in 1999, despite having experienced outbreaks of giardiasis in 1985 and 1990.

"The fact is," says Hrudey, "that chlorine is designed to kill bacteria so you can say it's a toxic chemical - bacteria are living things and they're being killed by chlorine. We know that chlorine was used in World War I to kill people - it's a toxic gas. So, yes, it's not something to fool with. But we've got 150 years of experience and millions of lives saved because we've been able to chlorinate water to prevent diseases. Currently, there are still millions of people dying around the world every year for lack of safe drinking water and adequate chlorination would probably prevent most of those deaths.

"Does that mean there are no problems with chlorine? Well, no. Chlorine in water can taste like medicine. I can understand why a lot of people prefer bottled water to tap water where the chlorine dosing is not managed very consistently so that fluctuating chlorine levels make it noticeable. But I don't think Edmonton water tastes bad and I would not waste my money buying bottled water in Edmonton because of taste."

Like most public health issues, drinking water safety involves social factors as much as technical details. Whether it's public perspectives on risk that are tied to aesthetic factors or the human nature aspects governing operator performance in water treatment plants, assuring we have safe drinking water requires consideration of many interdisciplinary factors. To take this into account the University of Alberta has created the new School of Public Health that uses an innovative, multi-faceted approach to help advance public health research, education and practice. The School covers all the core areas of public health from biostatistics, epidemiology and environment health to health policy and the socio-behavioural determinants of health with programs ranging from Global Health to Health Promotion.

But no matter how much education someone has, for drinking water safety what matters most is who's running the water treatment system and are they adequately trained to do the job of providing safe drinking water to large numbers of people who rely on them for their safety and, sometimes, their lives. To operate a water plant you currently need a high school education and some specific training related to the level of your responsibility as an operator. Is that adequate?

"Frankly," says Hrudey, "the most important thing is a person's personality and sense of responsibility. It's not a case of how much technical knowledge you cram into that person's head, what matters most is whether or not that person cares about people's health and understands that they are responsible for protecting the public from waterborne disease. You can train someone with a reasonable background to call for help when they're in over their head - and there's help to be found - so the best protection against having inadequate people doing the job is to train operators to know when they're in over their heads, when to call for help, and to assure that help is available when they call.

"What you can't do is to have people in charge of these systems who can't appreciate what they don't know and don't know what really matters. That's what happened in Walkerton. The Koebel brothers didn't set out to kill their neighbours. They lived in the town and kept drinking the water they were in charge of treating. They just had no clue that it was possible for them to foul up so badly that some of their neighbours would die."

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.