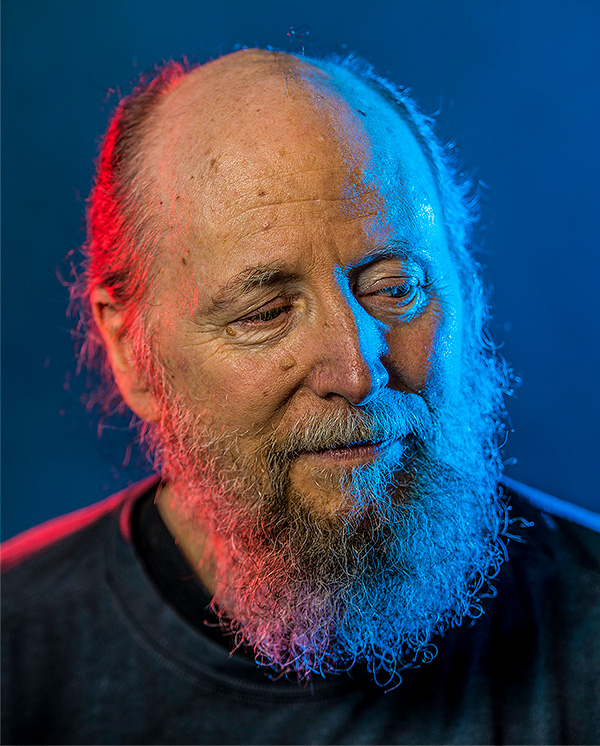

Photo Credits: John Ulan

The Fox Studios compound in Los Angeles is a sprawling 10-block mini-city inhabited by faux streetscape exteriors, airy sound stages, chic executive suites, quiet grassy spaces, funky cafeterias and dozens of suites and trailers full of precisely the kind of beautiful and glossy people you'd expect to find on a Hollywood lot. Of course, those people are merely personal assistants to the seriously beautiful and glossy stars of the various shows filmed on the lot.

Also interspersed throughout the compound, like weeds growing through cracks in the pavement, is a smattering of rundown '30s-era boarding rooms converted to ratty offices, now mostly occupied by the lowest order on the Hollywood phylum: writers. Not that writers aren't crucial to the process. Just about every funny or smart thing that comes out of Hollywood originated in the head of a writer, but writers are not beautiful or glossy (unless a sheen of flop sweat counts), which means that they are treated as dull and distant moons weakly orbiting the vitalizing power of the true heat sources - studio bosses. Hence the relegation to the old boarding rooms, which is where I meet up with Joel Cohen, '88 BSc, one of the head writers for The Simpsons. After Cohen shows me the endearingly cluttered cubbyhole he calls an office, we make our way a few hundred metres north to Building 1 for a "table read" of an upcoming script.

Table reads, Cohen tells me, are a big deal. It is not just an informal working meeting to tinker away at a script; table reads are a key moment in the production process, the point along the way where everyone involved in this multibillion-dollar, 28-season, 31-Emmy, seven-foreign-language franchise gets their first group chance to weigh in on whether the writers are earning their keep.

"These are our dress rehearsals," Cohen explains. "Because the show is animated, we rarely get live feedback, so this is our way to get an audience response."

What he fails to mention is that the "audience" usually consists of every star and executive attached to the show: the actors, as well as Matt Groening, the creator of the show; James L. Brooks, the producer of the show; and Al Jean, the "show runner" (who is the person really running the entire circus).

We step into a large conference room, which contains a huge oval table with seats for at least 30 people. Natural light floods the space, giving it the feel of a small church. I take a seat against the side wall along with another couple of dozen invited guests. The show's power brokers sit around the table. Beside them are various cast members, with some also on speakerphone. Conspicuously, there are about eight chairs lined up precisely against the rear wall, as if welcoming the featured guests at a firing line. This is where the writers sit.

"They always put the writers as far away from the talent as possible," Cohen says. "It's always been that way."

The mood around the table is hard to gauge - expectant and abuzz. A nervous anticipation bounces off the walls. It is the first official "reunion" of the full cast following a protracted and often-acrimonious dispute over salary between Harry Shearer (the voice of Mr. Burns, among many other characters) and the producers of the show.

The table read begins. Jean reads the direction notes and keeps things moving briskly. The A story features Smithers declaring his love for Mr. Burns. The jokes come fast and furious. There are songs. There are laughs. One of the lines that makes me laugh out loud comes when a character mentions something about the food chain and Homer, puzzled but suddenly attentive, says, "Where is this food chain you speak of?" (This joke was eventually cut from the final script when the episode, "The Burns Cage," screened in spring 2016.)

"One of the biggest motivations I have in my job and in my work, trust me, is to make the other guys in that writers' room laugh at something."

Many of the cast and executive strata offer up the occasional laugh. The invited guests laugh more often, but not at every joke. But the writers aren't laughing. They are all scribbling notes furiously. Throughout the table read, I don't once see a single writer laugh.

At the completion of the table read, Jean thanks the entire crew and says so long to those on the phone line. People stand. Many mingle. Brooks and Jean leave quickly. There is still a giddy hue to the air, as the writers and a couple of cast members hang around to chat. Nancy Cartwright, the voice actor responsible for Bart Simpson as well as some minor characters, generously makes the rounds, thanking people for coming out to watch and listen, as if we are the ones who've done her a favour. Cohen is at the back of the room, engaged in an animated discussion with a couple of the other writers. He finishes and comes over and suggests we go off-lot for lunch. When we get to his chosen spot - La Serenata, a Mexican joint on West Pico Boulevard, about 15 minutes from the Fox lot - I mention to him I'd noticed that none of the writers were laughing during the table read.

"Yeah," he says, half-scanning the menu, "but that's because the table read is for us to find out what other people think is funny. We want to hear what jokes are working and what ones aren't. I mean, you have to pay attention to the energy, or when people are confused, or when no one knows why the story took the turn it did. It's a big part of what we base our rewrite on."

He goes on to tell me that perhaps one of the reasons the writers don't laugh at the table read is, one, that it wouldn't be in the original script if they didn't think it was funny and, two, that by the table read stage, a script has already been through as many as a dozen story cycles, during which every one of them has pored over and finessed every joke a hundred times.

"We laugh at all the jokes," he says, grinning. "Of course! And one of the biggest motivations I have in my job and in my work, trust me, is to make the other guys in that writers' room laugh at something. That alone is hugely rewarding, to entertain these super-smart and talented guys."

Don't be falsely modest, I counter, suggesting they must feel the same way about him.

"I hate to disappoint you and the U of A," he says, stopping to wipe some salsa off his mouth. "But I am the dumbest guy in that room! Sorry, U of A! My education prepared me for nothing. Nothing!" He starts to mimic me writing in my notebook what his next words are going to be: and then he said, Of course I'm just kidding. It was a really important time in my life.

Except that isn't what Cohen says.

"That'll bum your editor out," he does say, "knowing the magazine completely wasted every dime to send you down here to talk to me when my education was actually totally wasted on me." He pauses, perhaps to lure me yet again into thinking he was finally about to express something earnest and heartfelt. Nope.

"Man, that has to suck."

100 Jokes a Day

Joel Cohen's life is a joke. Not in the pejorative sense, of course, but in the sense that the engine of his day, every day, all day, is the joke. Well, hundreds of them, actually. They are his oxygen, his nourishment, his job. He can't help but seek - and usually find - the humour in everything, but that doesn't mean he thinks everything is a joke. In conversation, he is, in fact, a relentlessly probing and intelligent person. It's just that he also happens to have a sharp and somewhat anarchic sense of humour. He's not a guy who makes irritating wisecracks out of everything anyone says. Rather, he is an inherently witty person who has been trained relentlessly, every day of his life for the past 15 years, to take the ordinary and find the lunacy underneath it. His humour is more Monty Python than Mel Brooks, full of literary allusions and (sorry, Joel) deep education but always tinged with an edge of satirical probing. Michael Price, another longtime Simpsons writer, started on the show around the same time as Cohen. "The first thing anyone notes when they meet Joel is how fast he is, how quick he is. The guy is funny and deadpan and likes to say unserious things in a very serious way."

One can only wonder where that came from, since "comedic hotbed" is not a term you'd immediately attach to Alberta in the 1970s. Cohen was born in Calgary in 1967. Though he has lived in L.A. for two decades now, he still has strong connections to Alberta. He returns a few times a year to Calgary, and his older daughter still attends a summer camp near Canmore that she has been going to for a decade. Both he and his wife, a nutritionist he met in high school, still have friends and family in Calgary. "And I haven't missed a Stampede in ages!" he says.

Cohen's father, who died three years ago, owned and operated the Uptown Bottle Depot for many years in Calgary. Cohen worked there as a teenager and remembers he was very popular with some of the homeless guys, primarily because he'd save them the dregs of the empties. Not the most ennobling job to have as a kid, but it did have its upsides. "I'd be walking downtown with my friends and we'd come across some street guy, and out of the blue, he'd say, 'Hey, Joel, my man!' and it was great!"

Cohen moved to Edmonton for university in the fall of 1985 "and much to the dismay of the U of A, I'm sure, they let me in." He enrolled in pre-med, studying organic chemistry because he thought if he took the hardest course it would give him the most options. "Which only establishes what an idiot I was," he says. "I failed, took it again and still only barely passed. So I left pre-med and took the science courses I was interested in, like zoology, which eventually led to a biology degree."

His years at the University of Alberta, he finally admitted to me, were significant to him. "The U of A gave me a knowledge base I could draw on and I'm thankful for that." He matured in those key years, though he still floated a bit, unsure what he was meant to do or even what his passions were. Not that they were unsatisfying years. "I had a really good time at the U of A. I met a ton of great people, hung out at HUB and the Power Plant, lived in residence, played intramural hockey. After my degree, I took another half year and just took every class that interested me, things like anthropology and computer programming. That allowed me to get a better sense of what I wanted to do with my life."

"Everyone is pitching [jokes] all the time and, like in baseball, even if you had a .300 batting average, getting three out of 10 jokes in, that'd be phenomenal."

After graduating, Cohen took a year off to travel through Europe and Africa, then did what every aspiring comedy writer does … an MBA at York University. "Honestly," he laughs, "I have no idea why I did that. I can't remember a single thing I learned there." He then moved on to work in Toronto for a now-bankrupt film distribution company in its home video department. He had discovered by that time that he wanted to try his hand at TV writing. Armed with a green card (his father had relocated to the United States in 1987), Cohen moved to Los Angeles in 1997 and got a job selling ads for Turner Broadcasting on CNN Asia and CNN Latin America. Shortly thereafter he met comedian Kathy Griffin, who was starring on a show called Suddenly Susan. She got him writing on that show, and his boss there - whose partner is George Meyer, a key player in turning The Simpsons from a cartoon short into a full animated series - set up an interview for The Simpsons. Cohen pitched a hundred jokes his first day on the job and, 15 years later, he's still pitching a hundred jokes a day.

Survival of the Funniest

The day-to-day process of creating the show - meaning the reality of Cohen's existence - is a combination of ceaseless originality married to inexorable routine. Typically, once a storyline is approved, the lead writer completes the first draft. Then Al Jean makes notes on the script. Everyone else in the writers' room makes notes on the script (the "writers' room" being both figurative and literal, in that the writers regularly leave their individual offices to congregate in a single meeting room to bounce ideas off one another, but also in that the writers' room is a notional space where the team works collaboratively on scripts in various stages of development). Then there are rewrites. Then more notes. Then more rewrites. Then more notes. Then they might finally arrive at a table read, after which there are further rewrites.

"It can be a nine-month process from the script getting handed in, to the show airing," says Cohen, "and the script might go through as many as 10 drafts, including when we get to animation. By the end of it all, there might be five per cent of the original script left. It can be an annoyingly iterative process, but the final outcome is always better than the first draft. You have to surrender to the collaborative process."

It's something of a humour factory, if only because that's the only possible way to produce a show with that much story, that many jokes, that many characters and that has been running for so long.

"The bottom line is that you just have to keep delivering and keep bringing it," Cohen says. "Like anyone's job, you have your small victories and your small defeats every day, but you just keep plowing away.

"Honestly, there's no magic in our job, and so much of it is just persistence. Everyone is pitching all the time and, like in baseball, even if you had a .300 batting average, getting three out of 10 jokes in, that'd be phenomenal."

The scale and volume of jokes being pitched is somewhat dizzying when you think about it. There are 10 to 12 writers in the room on any given day, and when they know they are working on one joke slot - meaning a moment in the show that they all know calls for a joke - they will spend an hour pitching jokes to one another and might come up with a hundred jokes. In one hour. For one single five-second joke slot. And then when they agree on a joke, it'll still go through five rewrites. And it still might not survive the table read. If it survives the table read, it'll still get rewritten another half-dozen times prior to animation and voicing. The ruthlessly Darwinian nature of a single joke's evolution is staggering to behold. For every joke that makes it on the show, there might have been a few hundred that didn't.

"That's not the worst, though," Cohen says with a laugh. "The worst is when we need a name for a character. It freezes the room. I'm not kidding. Doug? How about Doug? No, Doug's not funny anymore. How about Dirk? OK, that's funny. Let's go with Dirk. But what about a last name that you can pair up with Dirk?! Seriously, we sit there flipping through the phone book."

The only possible way to survive is through collaboration, Cohen says. The writers carry one another along. It's not competitive in the writers' room because that's a sentiment they don't have time for. It's so hard sometimes to come up with a joke that works, says Cohen. "You're just begging anybody to say something, anything, that's going to get in. You just surrender to the process because you need a team of people. You're just throwing man-hours at it."

Fellow writer Price says Cohen is pitching all the time, "and he was pitching fast the first day I met him 15 years ago. Which is good. When you're rewriting, you want someone who pitches a lot and who pitches good stuff but someone who also has the confidence to pitch bad stuff, because sometimes it's the bad stuff that inspires the next good idea or moves the needle in a different direction. There's no ego around any of that stuff because all we want is to just go home to our families."

Cohen likens the process to a rally in volleyball, which he called bump, set, spike. Someone introduces a joke idea - the bump. Someone advances the idea - the set. And then someone finishes the joke off - the spike. The person who spiked it might get the credit for the joke but, as Cohen notes: "Anything creative on the show has multiple parents.

"But don't get me wrong," he insists between mouthfuls of a tortilla, "there might be a lot of repetition to the days, and a lot of joke after joke after joke, and the pressure of always having to find something funnier or better … but we're working with something that is just so joyful that it's always great."

Perhaps the expression of genuine feeling caught him off guard, or maybe he was just talking with his mouth full, because he appeared to aspirate a black bean or small chunk of chicken. He began to choke, for real, and I momentarily panicked inside. I winched the Heimlich manoeuvre out of my memory. Thankfully, he recovered in short order - and was immediately ready with a joke, though spoken hoarsely. "As you can tell, this is very emotional. It's going to be very hard for me to get through this interview … though if I do choke and die, at least you'll have an audio recording of it."

A Modest Guy

Cohen loves his work. "I mean, let's face it, I haven't had to be out in the real world where I've actually had to reinvent myself, like, Now I'm a drama writer! Now I'm an action writer! …"

Yet he knows the day will come when he won't be part of The Simpsons, if only because the show might one day get cancelled. He has been working on a variety of secondary projects in the last year or two, including online shorts, feature films and other TV shows. He's also working with a couple of other Simpsons writers on an animated film and has tossed around a few projects with his brother Rob, who also works in L.A. and recently made a well-received documentary, Being Canadian.

"I'd love to see Joel be a show runner on a show he created," says Price. "He'd be terrific. The show would be funny, natural, full of smart observational stuff with a silly side."

"I'm always dabbling," says Cohen. "I love The Simpsons and want to stay as long as I can, but I also feel like I'm ready for the world outside the show whenever that happens. But I think you've got to keep fresh, and you've got to keep judging yourself against an outside arbiter. I mean there's a lot of horrible stuff out there … and I want to write something horrible on my own one day! I need the freedom to fail!"

His sardonic self-deprecation isn't just for my sake. He comes across as a fundamentally modest guy. When he won the award at the 2014 Writers Guild of America for best animation writing, he accepted saying, "I pitched a story idea at our annual writers' retreat that was so horrible it was immediately rejected and the producers double-checked my contract to see if they could get me off the show. But [Simpsons producer] Jim Brooks, in his generosity, gave me this idea, and with everybody's help I wrote it. So I'd like to dedicate this award to every kid who hopes to be so pathetic that one day an Oscar-winning writer will give him an idea."

Too soon, Cohen and I finish our lunch. He asks me how it was. "Great," I reply. Our waitress comes by, picks up our plates and asks how our meals were.

"Delicious," Cohen says. "Except for my friend here. His was terrible." He looks at me. "Go on. Tell her. Don't be shy."

"He's kidding," I tell her. "It was good."

It's too late. Left eyebrow hoisted, she backs away, slowly. Cohen allows himself a small grin. It doesn't occur to me until later that he had bumped and set, but I didn't have the wherewithal to spike. ("It's not your fault," the funnier me would have said to the waitress, "but I'll let you know what my doctor says.")

Cohen and I stand and part ways so he can go dig in with his fellow writers on the notes from the morning's table read. You can tell he's happily anxious to get back at it. His obvious embrace of the show's work ethic, even after all these years and all this success, makes me think of the classic mantra of athletic achievement: process, not outcome. Joel Cohen has both surrendered to, and mastered, The Simpsons' collaborative process because it perfectly suits his whip-smart but self-effacing personality.

The bonus for the rest of us is that the outcome isn't half bad, either.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.