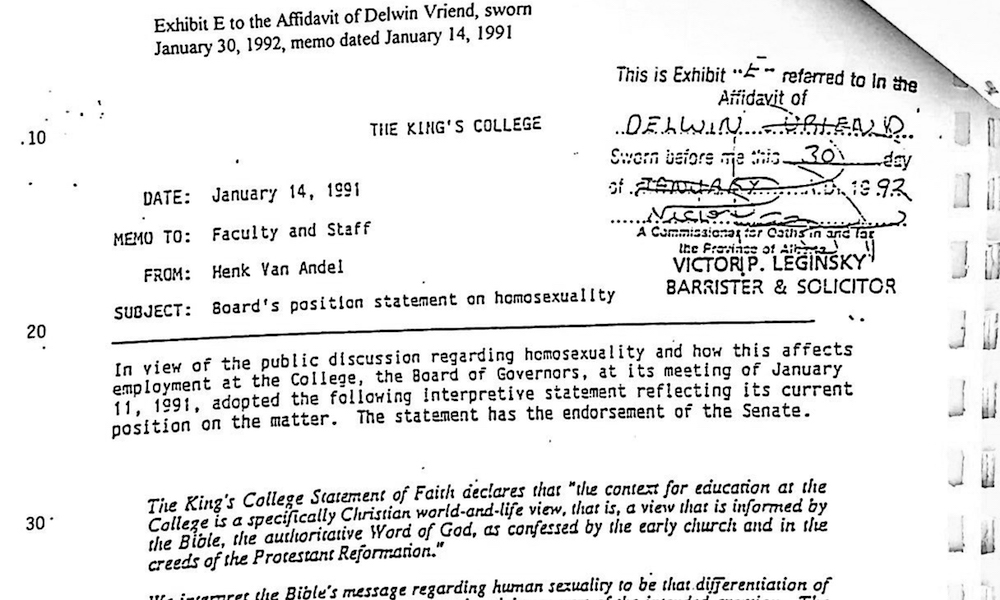

In 1991, the King's College in Edmonton fired Delwin Vriend, a laboratory co-ordinator. The official reason for the firing: Vriend was homosexual. When Vriend tried to file a complaint with the Alberta Human Rights Commission, he was told Alberta legislation did not include homosexuality as a protected ground.

So Vriend took the provincial government to court.

Seven years later, in 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada decided unanimously that Alberta's lack of protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

This year, on March 19, the inaugural University of Alberta Chancellor's Forum marked the 20th anniversary of Vriend versus Alberta with a lively panel discussion moderated by Paula Simons, '86 BA(Hons), city columnist for the Edmonton Journal. Five Albertans who were active in the case or in the LGBTQ2 community of the day shared their recollections of this landmark case, including one judge's refusal to even look at Sheila Greckol during her argument to the court.

The Players

Sheila Greckol, '74 BA, '75 LLB

Current position: justice of the Alberta Court of Appeal

Role at the time: lead counsel for Delwin Vriend

Julie Lloyd, '91 LLB

Current position: provincial court judge

Role at the time: co-counsel to Canadian Bar Association and an intervener on the case

Michael Phair

Current position: chair of the University of Alberta Board of Governors

Role at the time: Edmonton city councillor

Doug Stollery, '76 LLB, '80 LLM

Current position: chancellor of the University of Alberta

Role at the time: co-counsel for Vriend

Kristopher Wells, '94 BEd, '03 MEd, '11 PhD

Current position: faculty director for the Institute for Sexual Minority Studies and Services and assistant professor in the Faculty of Education

Role at the time: a U of A student, then a new teacher

The times

Vriend's choice to take the province to court in 1993 was a bold move, unprecedented in the day. At the time, the world was reeling from the AIDS epidemic and open homophobia was commonplace in Alberta and elsewhere.

Michael Phair: There were people who'd say, "People who get AIDS deserve it. They should all die anyway. They're just gay, and they have no place here."

In my case, a lot of people that I knew in their 20s and 30s were dying of AIDS. And, yet, we had this kind of [discrimination] going on at the same time. It was a very ugly time, in many ways. And, for reasons I don't exactly know, in 1992 I decided to run for city council. And I won, which was even more of a surprise.

Kristopher Wells: I graduated from the Faculty of Education in 1994, in the midst of this case working its way through the court.

You couldn't be out as a teacher. You'd be concerned about being fired from your job. I'd go to Safeway on Sunday night with my partner, grocery shopping. And, he'd put his hand on my hand on the cart, and I'd freeze. If somebody saw that, on Monday morning I wouldn't have a job.

I ended up teaching in the same community where I went to school, St. Albert. I walked through those halls as a closeted student and I had to be a closeted teacher. It eventually became unbearable. I left education because I couldn't be the kind of teacher that I needed when I was a student.

Archival footage of Edmonton's Gay Pride Parade in 1993 (CBC)

The case in Alberta

When Vriend's lawyer Victor Leginsky, '75 BEd, '82 LLB, brought the case before the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta, the judge, Anne Russell, '62 BA, '63 LLB, ruled that the province's law was indeed unconstitutional. However, the provincial government, under then-premier Ralph Klein, took the case to the Court of Appeal of Alberta.

Greckol, a labour lawyer at the time, agreed to represent Vriend at this stage of the process, but she needed help. The hunt brought her to Edmonton's 1994 gay pride parade, where she enlisted Stollery. "It turns out, in those days, people were not banging down the doors to represent a gay man," Stollery said. "So, there I was." It was the start of a lifelong friendship between the two lawyers.

Greckol, Stollery and their co-counsels, June Ross, '76 BA(Hons), '79 LLB, and Jo-Ann Kolmes, '87 LLB, argued before Court of Appeal that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms protected homosexuals from discrimination, even if it didn't say so specifically. Vriend, they asserted, should be able to protest his dismissal before the Alberta Human Rights Commission.

At the Court of Appeal, Vriend's legal team received a very different reception. In fact, Judge John McClung, '57 BA, '58 LLB, swivelled his chair to face the wall when Greckol presented her arguments. Unsurprisingly, McClung reversed Vriend's earlier victory. His blunt and impassioned written decision sent shock waves through Edmonton's gay and lesbian community. (McClung died in 2004.)

Sheila Greckol: That judgment used very graphic language. It said, for example, homosexuality is against "millennia of moral teaching."

Phair: When McClung's written statement came out, what he actually said was so degrading and so awful. It was hard to not feel cheapened.

Wells: The public reaction was, "it's open season." Walking down the street, in the gay pride parade, there were still people with paper bags over their heads. That was what I remember the most from my very first pride parade in the mid-'90s. Because people were worried if someone saw them or they were on the news the next day, they'd be fired from their job. There was a lot of fear and insecurity in the community. And our highest provincial court was authorizing it.

The final appeal

There was one more place to plead the case: the Supreme Court of Canada. There, Greckol, Stollery and their team had assembled a formidable array of interveners to support their case. Among them were the Canadian Bar Association (whose team included Julie Lloyd), the Canadian Labour Congress, the United Church of Canada, the Canadian Jewish Congress and many others.

In appealing the decision to the Supreme Court, Vriend's legal team made the bold decision to use McClung's own provocative words in their application.

Stollery: There was a line in the judgment of Justice McClung. He was quoting from the Dred Scott case, the historic slavery case heard in front of the United States Supreme Court: "I'd rather trust my dinner to a dog than this case to the Supreme Court." And that was the very first line of our application to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Greckol: It was almost visceral, the kind of emotion the McClung judgment evoked. If anybody's interested, it's online. And I think it was a powerful argument before the Supreme Court of Canada, to read that judgment and see what the temperature was in Alberta and elsewhere. As it turned out, ironically, it probably helped us.

Julie Lloyd: It was like a body blow, reading that stuff when you're a member of that community. And then to see those arguments roll into the Supreme Court of Canada, and then just burst like little bubbles. All of those toxic arguments, that "this is morality" or "this is about religion." These arguments disappeared into smoke as each of the interveners stood up. It was a really powerful experience for me.

The backlash

On Thursday, April 2, 1998, the court released a unanimous decision: the Charter of Rights and Freedoms expressly prohibited discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Within hours, social conservatives in Alberta began lobbying the Klein government to invoke the notwithstanding clause, a last-resort legal tool that would allow the province to override the decision.

Phair: It was probably the toughest time for me in all my time as a city councillor - one of the toughest times, probably, in my whole life.

On Sunday [three days after the decision] it just exploded - on the radio shows, on the media. On Monday, in my office at city hall, we started to get calls from people saying awful things - stuff about getting rid of me and people like me. There were so many calls coming in that the city had to bring in a couple of temporary people to help. To this day, I feel for those people who had to deal with all those calls.

Stollery: Within a couple of hours of the judgment, media were interviewing a woman who was heading up Alberta Women United for Families. She was opposed to the decision, and the arguments she was raising were certainly ones we'd heard before. But behind her was this giant poster: "Invoke the notwithstanding clause." And I thought, "Where did that poster come from?" Because the decision was only a few hours old.

The opposition had been preparing for the judgment. The moment it came out, an advertising campaign started - print, radio, television. I don't know how many hundreds of thousands of dollars went into that campaign. All there, all canned. Here's your postcard; send it in to the premier. In some of the churches, on Sunday, postcards were being handed out - pre-done, sign here, send it in.

My dad [Bob Stollery, '49 BSc(CivEng), '85 LLD (Honorary)] had a fax machine he was very proud of. Very modern. He hand-wrote a letter to the premier. I went over one night, and there he was. I said, "What are you doing?" He said, "I'm feeding this into the machine." And I said, "But, you've just done that." He said, "Well, of course. As soon as it comes out, I feed it back in again."

My dad, realizing there were only nine of us on our side, and three and a half million on the other, was determined to increase the number of letters from our side.

The support

The initial backlash was followed by an even greater groundswell of public support. One week after the Vriend decision, the Klein government backed away from the idea of invoking the notwithstanding clause.

Although Vriend versus Alberta was just one legal case, its influence on Canadian society was instant, and is ongoing.

Lloyd: It reminds us how central equality is to democracy. It tells us that this is a group of people who we need to celebrate, and not discriminate against. It reminds us who we are as a country. The volume of that decision increases over time.

Wells: Right after the Vriend decision, the Alberta Teachers' Association was one of the first major institutions in our province to take action. They brought forward a resolution, before their annual representative assembly in 1999, to put sexual orientation into the code of professional conduct. The code is like the Charter - it doesn't change easily. It had to go before all of the teachers in the province to vote. There were protests outside the assembly. And, when it came time for the teachers, they voted overwhelmingly in favour.

It set the ATA in motion for the next decade. In 2003, they became the first teacher association in Canada to include gender identity. Think about that: 2003. In 2005, they passed a resolution to support gay-straight alliances in schools. It would take the government 10 years to catch up to where the teachers were for GSAs.

The reverberations

Reflecting on the Vriend decision 20 years later, the panel members view it as a template for extending equal rights to other marginalized communities.

Lloyd: When Vriend was done, then I started to get a lot of phone calls from trans people. I was surprised. I had more employment cases where trans people were saying, "I need to come out at work. I need to transition."

Wells: It was that galvanizing moment, where allies and community came together to fight back against what was government oppression - and won. We realized we could keep using the law and the tools that are available, people like Julie and others who were plodding along, striking down the legislation, making the changes that the government wasn't going to make on its own.

I think the case created a pathway for others to walk. We're seeing that play out right now in our school systems, where trans youth are still fighting to be able to use the bathroom. And the visceral kind of backlash, the stereotypes that are being portrayed of gay and lesbian people 20 years ago, are what many trans individuals are dealing with now. I'm hopeful we can build these coalitions and these allies.

Paula Simons: When I spoke to Delwin Vriend last month, he said that in his mind this was always as much about trans people as anything else. It was about equality for everybody.

Lloyd: The way Sheila managed this case really underscores the importance of allies. Sheila was careful to bring along interveners. And after the Vriend decision, when this whole notwithstanding stuff hit the fan, there were a lot of allies. It's not fair to make Michael come forward for the impugned minority and say, "Please don't hate me." It doesn't have the effect of people who are allies coming forward, who are already in the mainstream. It's our role to be those allies, those voices for our trans brothers and sisters. That's a lesson Vriend taught us.

Greckol: Those of us that have a voice, we need to be the ones standing up. It's so much more difficult when you're the subject of discrimination than when you're there as an advocate standing up for what's right.

I think about First Nations people. It's got to come from the community first. But then everyone has to chime in. Are we doing that enough for First Nations people? That's what I'm thinking about right now. Are we?

We need to be always conscious that there's somebody who needs our voice.

Stollery: We have to be aware of our history. And we have to fight every day to maintain the rights we've gained, and to make sure those rights are available not only to us, but to everyone.

In 70-plus countries in the world, it's a criminal offence to have a same-sex relationship. In 10 countries, the penalty is death. We've made great progress in Canada, but easily half of the population of the world today lives in an environment where they can be imprisoned or executed for being who they are.

There is one positive thing I can say to that. A recent decision of the Supreme Court of Belize struck down the anti-sodomy laws of that country - citing Vriend versus Alberta.

Panelists' comments have been edited for length and clarity. Watch the full panel discussion here.

Read more about the Vriend decision

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.