Socio-ecological Context

The

Richardson Mountains, located at the Northwest Territories

and Yukon border, are an area of high traditional use by

the Gwich’in and Inuvialuit People. A number of Gwich’in

archeological sites exist along the main drainages, and

various routes and family trails have been established

generations ago to travel between hunting and meeting areas

(Haszard and Shaw 2000). Nowadays, the Richardson Mountains

are still widely used by the Gwich’in from Fort McPherson

and Aklavik, the Vuntut Gwitchin from Old Crow, and the

Inuvialuit from Aklavik, and are considered a prime area

for hunting large mammals such as caribou

(Rangifer

tarandus), moose

(Alces

alces),

Dall’s sheep (Divii in Gwich’in, Ovis

dalli dalli), and

grizzly bears (Shih, Ursus

arctos). The

Richardson Mountains fulfill the subsistence and

recreational needs of many northern peoples. Moreover,

local communities have recently expressed an interest for

developing an outfitting venture in these mountains.

Although the area is presently relatively pristine,

forthcoming oil and gas development in the adjacent

Mackenzie Valley may leave a heavy footprint. Indeed, if

the Mackenzie Gas Project goes ahead, the Richardson

Mountains are predicted to be developed within the next 30

years (Holroyd and Retzer 2005). Exploration surveys have

already started in summer 2006 (Devon Canada’s geological

field trip), and more is to be expected next year.

Additionally, the Arctic is among the most impacted biomes

by climate change (ACIA 2005, Walther et al. 2002). A rapid

warming will likely influence abundance and composition of

vegetation, wildlife, and parasite species. The Richardson

Mountains are therefore likely to undergo significant

changes in the future, and there is a need to assess the

current species’ status and interactions in order to

monitor future changes and ensure sustainable management of

land and wildlife in this region.

Dall’s sheep in the Richardson Mountains are a relatively

small and isolated population at the northeastern limit of

the species range (Valdez and Krausman 1999), and seem to

be declining since the mid 1990s. The latest census counted

700 individuals (2006 GNWT, YTG & GRRB survey, unp.

results), about half the estimated 1997 population.

Furthermore, the 2003 survey reported low recruitment

rates, as evidenced by a low lamb:ewe ratio, low lamb

survival, and an old age structure (J. Nagy, GNWT, personal

comm.). Prior research by Barichello et al. (1987) and the

Gwich’in Renewable Resource Board (GRRB; Auriat 2005)

identified the range, movements and habitat use of this

population, and provided disease and physiological

information. These radio-tracking studies were however

focused on rams, and little information is available on

ewes. Because ewes play an essential role in population

recruitment, there is a need to learn more about this class

of the population. Harsh climatic conditions and

overgrazing have been identified as limiting factors, but

the impact of predation has received little attention so

far. Wolves and grizzly bears are common predators in the

mountains, although very little is known about their actual

demographic parameters (abundance, composition), habitat

use, nutritional ecology, and impact on this sheep

population. Local and traditional knowledge have reported

observations of both grizzly bears and wolves preying on

sheep (Shaw et al. 2005).

Grizzly bears are a species of Special Concern in the

Northwest Territories (COSEWIC 2002). They have large home

ranges and slow life history traits, which make them

vulnerable to the loss of few individuals. Upcoming oil and

gas development in our region may increase their

vulnerability and mortality rate (Edwards et al. 2005). On

the other hand, research in Alaska identified grizzly bears

as the main predator of caribou calves (Adams et al. 1995),

and their role as a potential ungulate predator seems to be

more important during the first few weeks of life (see

Zager and Beecham 2006 for a review). We suspect that they

may also be a limiting factor for Dall’s sheep,

particularly for the lamb segment of our study population.

At present, the productivity of grizzly bear females in the

Richardson Mountains was studied from 1992 to 2000

(Branigan 2000). However, critical habitat and habitat use

patterns still need to be identified, and grizzly bear

predation patterns and nutritional ecology also need to be

investigated. This information is essential not only to

understand the influence grizzly bears may have on Dall’s

sheep, but also to update and expand important baseline

information on bears in the Richardson Mountains.

According to recent community consultations, wolves

(Zhoh, Canis

lupus) are

believed to be stable to increasing in the Richardson

Mountains. Wolves can significantly limit mountain sheep

populations (Sawyer and Lindzey 2002), and research in

Kluane and Denali National Parks have demonstrated that

they represent a major mortality factor for Dall’s sheep

(Mech et al. 1985, Murie 1944, Sumanik 1987). Arctic wolf

populations also rely on other ungulates, such as caribou

and moose, and some packs tend to follow barren-ground

caribou herds in their migratory paths (Walton et al.

2001). In the northern Richardson Mountains and on the

Yukon North Slope, wolves seem to depend mostly on moose

and, seasonally, on the Porcupine Caribou herd (Hayes and

Russell 1998, Hayes et al. 1997, Hayes et al. 2000). Recent

range-wide decline of barren-ground caribou in the

Northwest Territories (DENR 2006) has lead to question the

impact of wolves on caribou, and also to wonder if

alternate prey such has Dall’s sheep will suffer from

higher predation rates as a consequence to lower caribou

availability (i.e. prey switching, Dale et al. 1994).

Additionally, wolf packs surrounding the Dall’s sheep range

area benefit from year-round prey sources, such as the

sheep, moose, and smaller mammals, and may be resident of

the area. Depending on the wolves’ movement pattern and

spatial dynamics, encounter rates and predatory pressure on

Dall’s sheep could vary substantially. Understanding the

wolves’ spatial and predation patterns will help in

assessing their impact on Dall’s sheep and other ungulate

species of the Richardson Mountains.

Objectives

This

project was designed to update and expand our ecological

knowledge about the dynamics and interactions between

Dall’s sheep, grizzly bears, and wolves at the spatial

level. There is clearly a need to understand the

spatial ecology of those

species, their

interactions, and

the

factors driving their interactions. I am

particularly interested in:

1. Describing home ranges and movement of Dall’s sheep,

grizzly bears and wolves, to increase the available

baseline information on those populations;

2. Characterizing the level of static and dynamic

interactions between the three species;

3. Understand how the habitat use and interactions between

the three species (movements and predation rates) may be

affected by habitat features such as vegetation, elevation,

slope, and aspect.

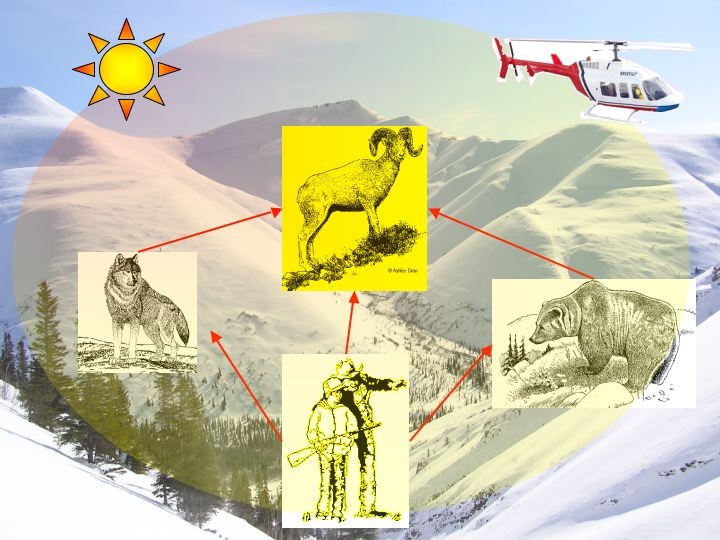

...I invite you to click on other sections to discover how

the data was collected and what results are emerging so

far. I conclude this section by a diagram summarizing the

complex interactions affecting this system, including:

Dall's sheep predation by wolves and grizzly bears, human

harvest of the three species, climate warming, and

sensorial disturbances from development and research

activities (helicopter). Other wildlife species, disease

and range condition were omitted from this figure because

of my limited design capabilities!