The consolidated data (2015 to June 2022) only includes contributions that were self-reported by university contributors. Thus, it may not encapsulate the entirety of work undertaken during this time period. For additional details on the methodology, please see below.

The collected data will form a baseline for reporting on the progress of Braiding Past, Present and Future. Following the 2023 TRC Report to Community Dashboard launch, updated reports are anticipated biennially.

The dashboard aims to distinguish between permanent structural responses to the CTAs and occasional or singular offerings. This distinction is vital to assess the enduring integration of structures, programs, and processes concerning Indigenous Initiatives within the university's operational framework, promoting sustainable and lasting change.

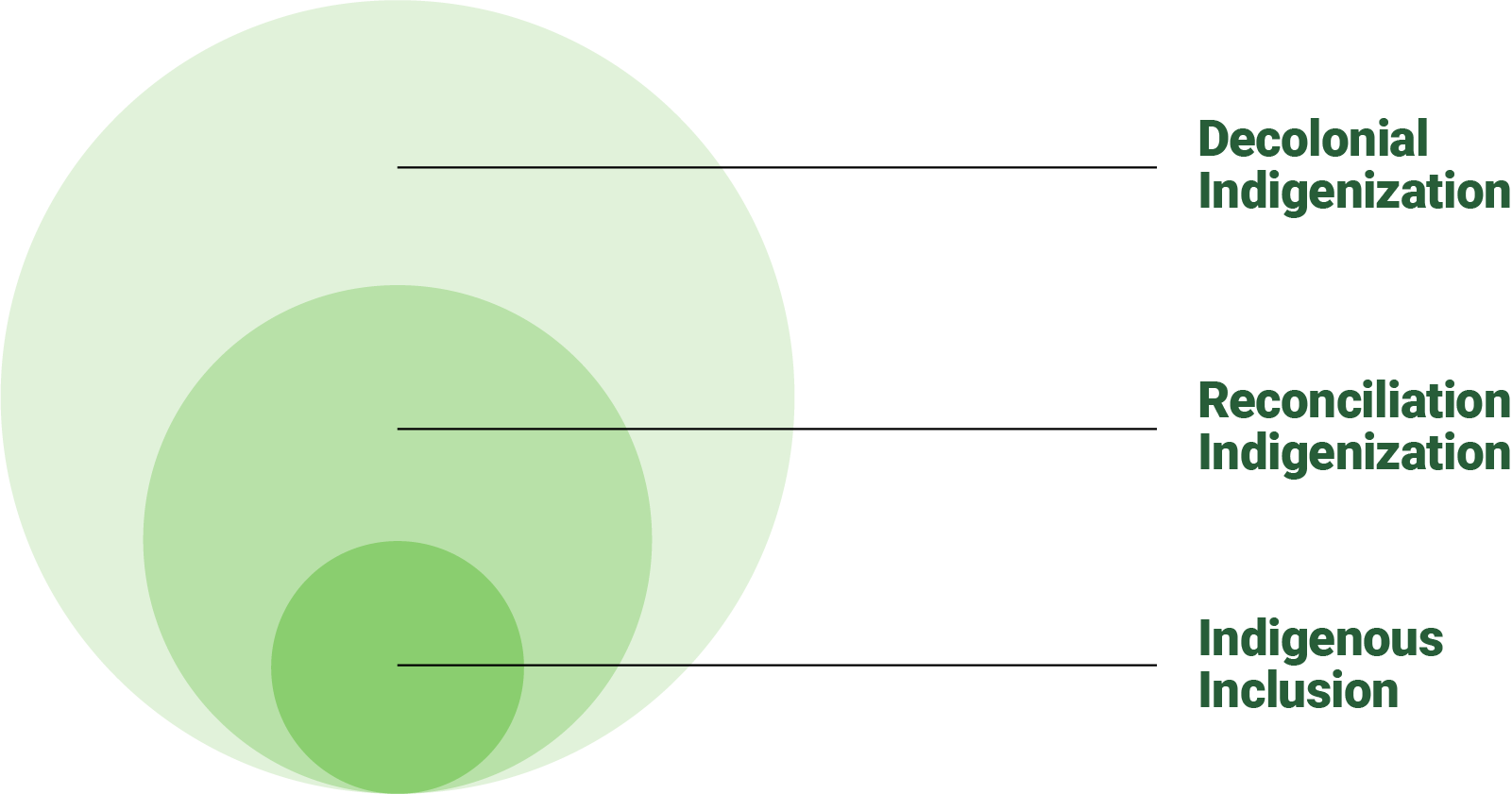

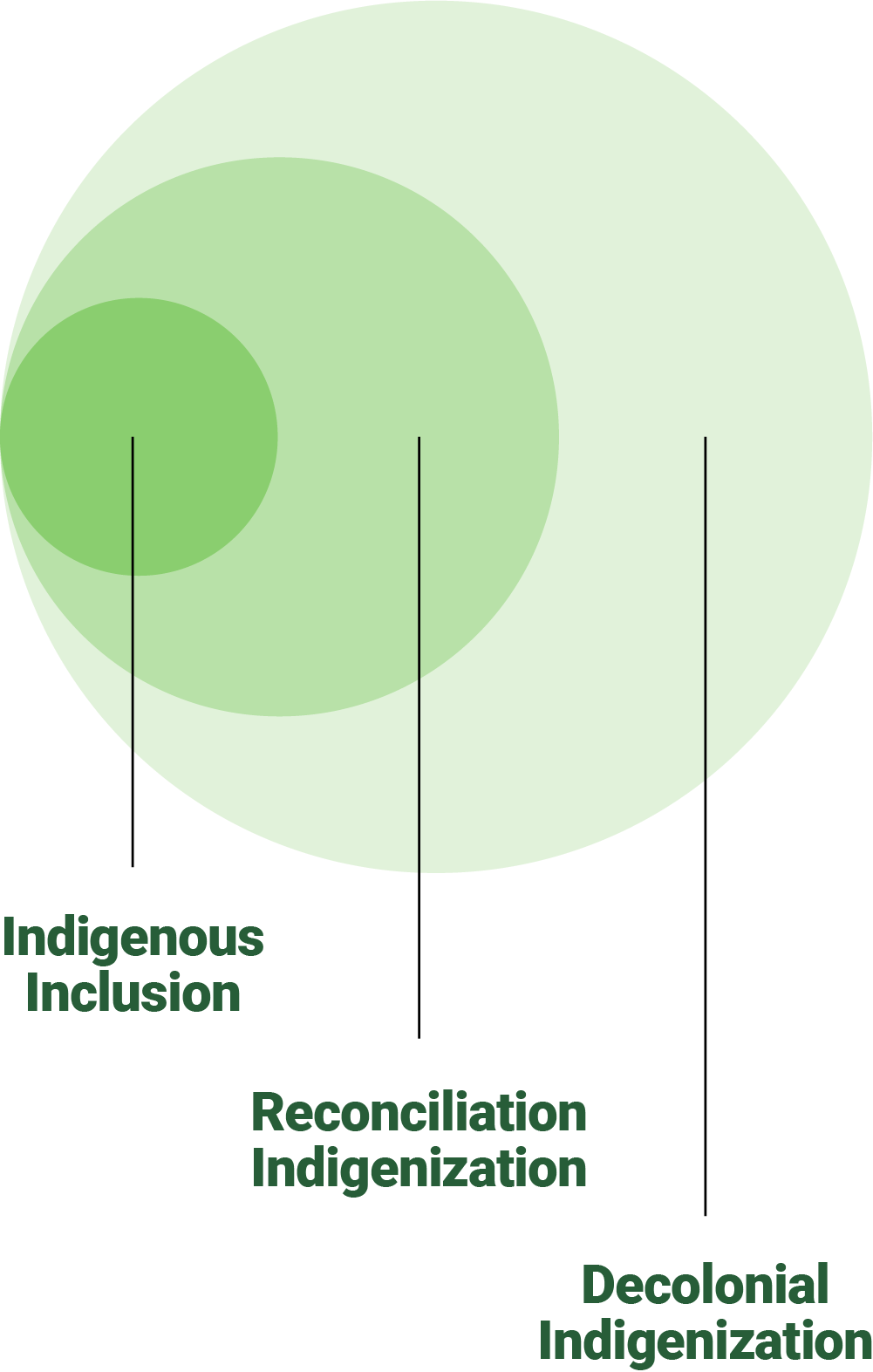

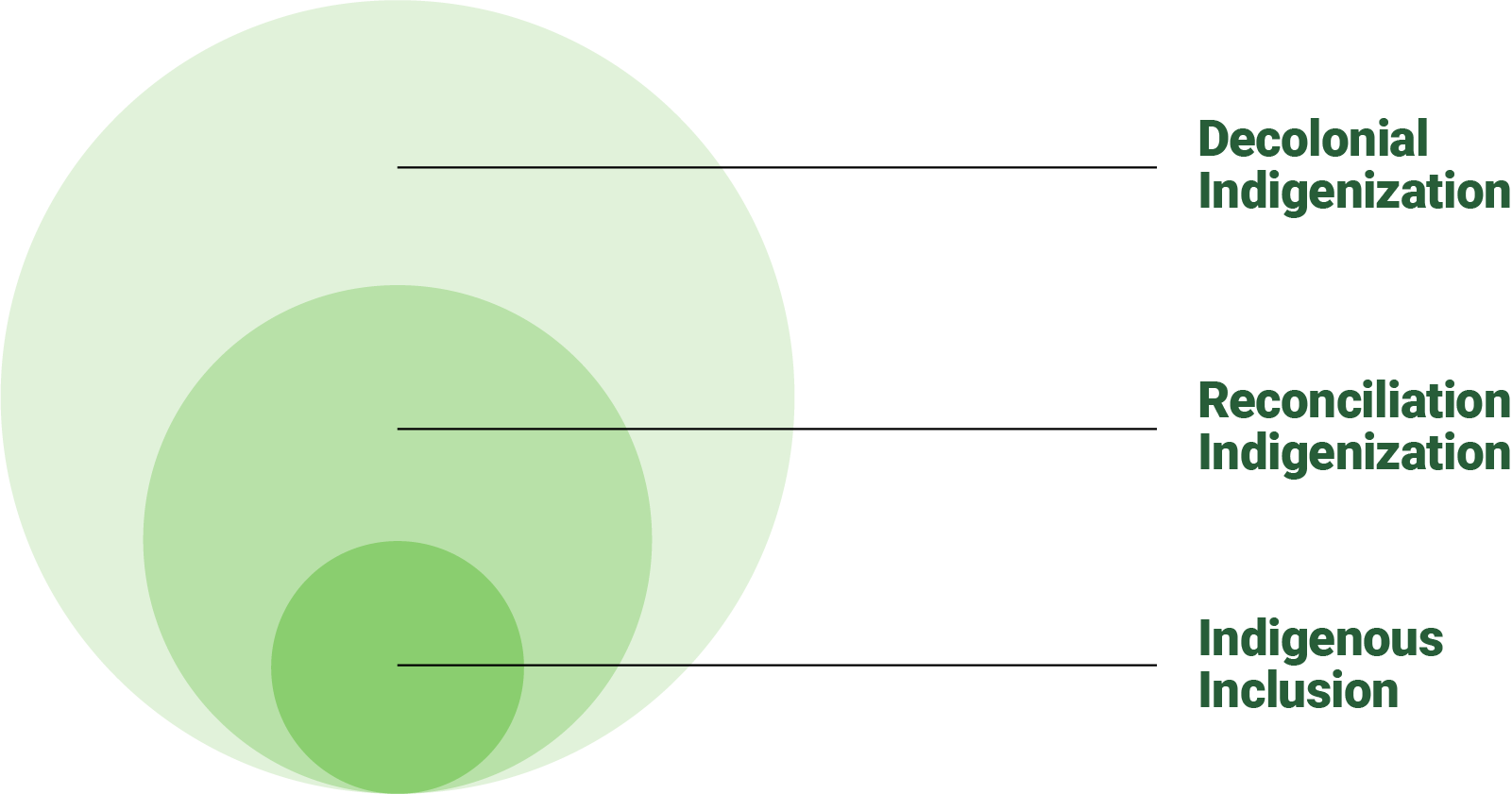

Consistent with Braiding Past, Present and Future: University of Alberta Indigenous Strategic Plan, and the work of Gaudry & Lorenz (2018)[17] , we use the terminology of Indigenous Inclusion, Reconciliation Indigenization, and Decolonial Indigenization an evaluatory benchmark.

Throughout the data gathering for this report there was evidence that the University of Alberta, as One University, is moving from “Indigenous Inclusion” into “Reconciliation Indigenization.” Different faculties and units are at different places on this continuum but, as an institution, there is evidence of “A vision that locates indigenization on common ground between Indigenous and Canadian ideals, creating a new, broader consensus on debates such as what counts as knowledge, how should Indigenous knowledges and European derived knowledges be reconciled, and what types of relationships academic institutions should have with Indigenous communities.”[18]

Throughout consultations on the university’s new strategic plan, Indigenization was identified as a key priority across institutional spaces. Shape makes clear that there is a deep commitment to reconciliation and Indigenous initiatives and one that represents the collective vision of the U of A community. Shape builds on the commitments set out in Braiding Past, Present and Future to enable transformative institutional practices that will move the institution forward along the continuum described by Gaudry and Lorenz.

Indigenous Inclusion

A policy that aims to increase the number of Indigenous students, faculty and staff in the Canadian academy. Consequently, it does so largely by supporting the adaption of Indigenous people to the current (often alienating) culture of the Canadian academy.

Reconciliation Indigenization

A vision that locates indigenization on common ground between Indigenous and Canadian ideals, creating a new, broader consensus on debates such as what counts as knowledge, how should Indigenous knowledges and European derived knowledges be reconciled, and what types of relationships academic institutions should have with Indigenous communities.

Decolonial Indigenization

Envisions the wholesale overhaul of the academy to fundamentally reorient knowledge production based on balancing power relations between Indigenous Peoples and Canadians, transforming the academy into something dynamic and new.