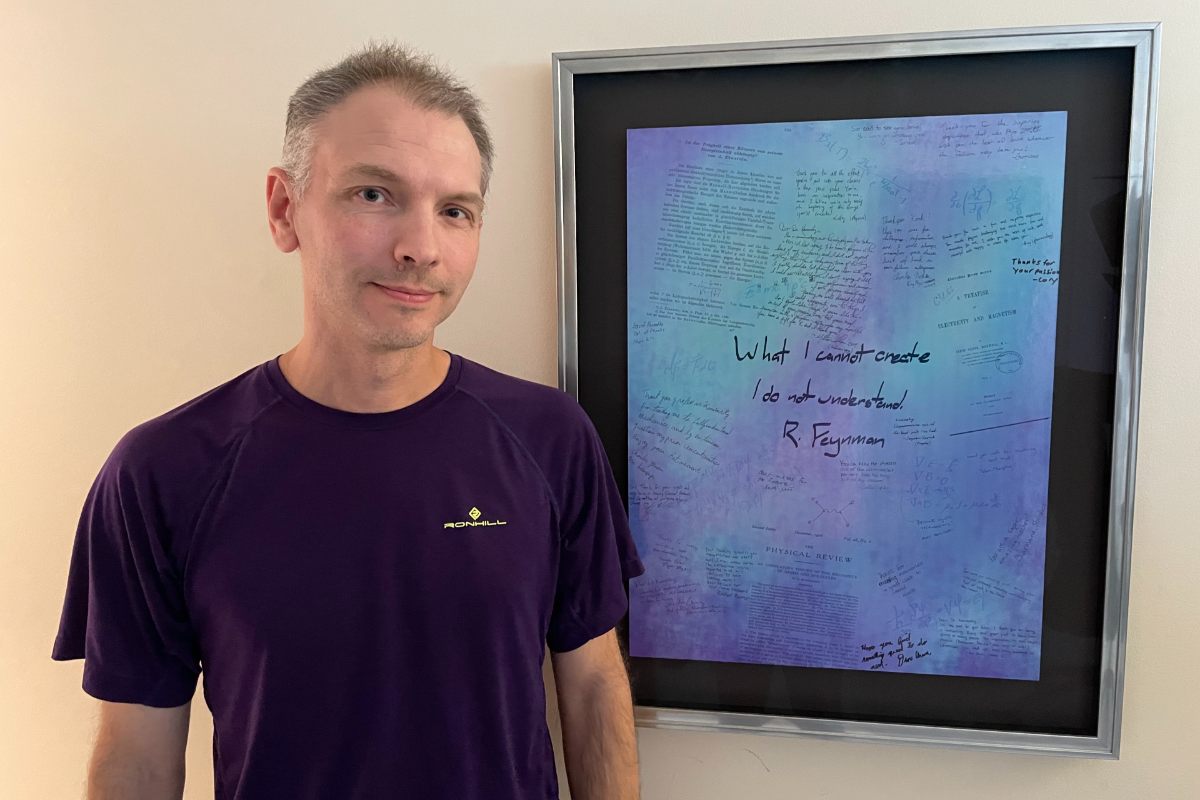

Let’s Talk Teaching: Meet Kirk Kaminsky

Andrew Lyle - 15 December 2021

Student engagement and the elusive “a-ha!” moment are what motivate Kirk Kaminsky, instructor and undergraduate physics advisor in the Department of Physics.

“Physics is hard. But almost anything that is worth doing in life is hard,” said Kaminsky. “And from hard work itself can emerge some of the greatest happiness possible.”

Kaminsky is passionate about teaching and sharing his expertise in physics with his students. Hear from him on the importance of perseverance and motivation, the elegance of physics, and pride in working at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Science.

What do you teach?

Physics courses, primarily at the 100 and 200 level.

What do you love about your field?

I think Steven Weinberg—Nobel Laureate on electroweak unification and sadly recently deceased—most elegantly and succinctly expressed my answer to this: "The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things that lifts human life a little above the level of farce, and gives it some of the grace of tragedy."

Physics is precisely this at a fundamental level and enables us to transcend our often irrational human condition, and is probably what I love most about it. Otherwise, I'd probably be here all day answering just this one question, leaving nothing to share with my students.

What should students who are interested in this topic know?

First, that (almost) everybody finds it hard, both mathematically and conceptually—one is always in good company there. Einstein captured it perfectly: "Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics. I can assure you mine are still greater.”

My point is that physics is hard. But almost anything that is worth doing in life is hard. And from hard work itself can emerge some of the greatest happiness possible.

Second, my teaching experience has confirmed in my bones that learning—all learning—is inextricably tied to motivation. If you come into a subject that you a priori dislike, you will not be motivated to learn—and the grade is unlikely to follow. But the grade will follow (typically) if you are motivated to learn and focus on the material first. To paraphrase the fictional Morpheus—from the movie, not mythology—as a teacher of physics, I can only show you the path, you must walk the path yourself. Physics is all about doing, not merely about watching and regurgitating.

Finally, one must discard the impression that physics is about hunting for the correct formula on a formula sheet to stick some numbers into a calculator. Early university physics is largely about the application of powerful general laws to the analysis of physical systems—about learning how to approach problems and problem-solving analytically. And these are skills that transfer across domains.

Tell me about your passion for teaching. What inspires you?

Student engagement and that sought-after look of wonder on faces (when I'm so lucky); the infamous “a-ha!” moment when that sudden, sometimes subtle manifestation of comprehension appears that every teacher instantly recognizes. The questions students ask. The occasional laughter I can engender from students, including the few times we are all in tears from laughing so hard (don't ask about the Great Molasses Flood of 1919, or the first ever final exam I designed under some odd advice from my PhD supervisor). The post-class group conversations about physics, about life. Or after working with, say, a pair of students, watching one student explain in their own words to the other what I've failed to convey, thereby confirming that the absolute best way to learn anything is to have to try and teach it to somebody else.

How do you cultivate a community of practice with your fellow instructors?

Most recently and pertinently to this question, I was the convenor for the six sections of EN PH 131 this past Winter. As a first-time convenor for a huge, very visible course offering that had never been fully taught online before, it was a somewhat daunting prospect to be responsible for more than 800 students we would not meet in person, with a brand new course format and assessment scheme. I really got an opportunity to cultivate a community of practice with the six other co-instructors precisely by adopting the very communication tool to which my own students had introduced me: Discord. My fellow co-instructors took to it like water, and this really helped us stay sane all Winter term.

What is one thing that people would be surprised to know about you?

The thing that immediately comes to mind is how I came to be a faculty lecturer. After leaving string theory research after my first postdoc (I joke that a good deal of my brief research career involved calculating the number zero), I returned to the University of Alberta and did an education after-degree with the intention that I would go on to teach calculus to secondary students. Quite literally as a consequence of a serendipitous meeting at the U of A bookstore with our former, now-retired associate chair Zbyszek Gortel, who learned I was back from California, I was invited to do sessional work for the department while completing my bachelor of education. I was encouraged to apply and the rest is now of course history.

In the end I never directly ended up using my bachelor of education to work in secondary education. The lesson appears to be that our careers can easily end up along somewhat different paths than we anticipate—it is without exaggeration a direct result of that random encounter that I am here writing this, right now.

Favourite thing about working at the Faculty of Science?

The glib answer is my office. I have a beautiful year round, south-facing view of the quad from the fourth floor of CCIS. The more serious answer is the staff and faculty in the Faculty of Science with whom I get the privilege to work alongside—from our always-knowledgeable and helpful faculty advising staff to my department teaching and administrative colleagues, to our down-to-Earth, straightforward, well-reasoned leadership team; this is a professional faculty about which we can be proud. I am originally from Edmonton, and every time I walk into the hustle, bustle and excitement that is CCIS, I honestly feel how lucky I am to get to work in my chosen field, in my home city with such an incredible community of people.

Curious to learn more? Find more information on teaching and learning in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Science.