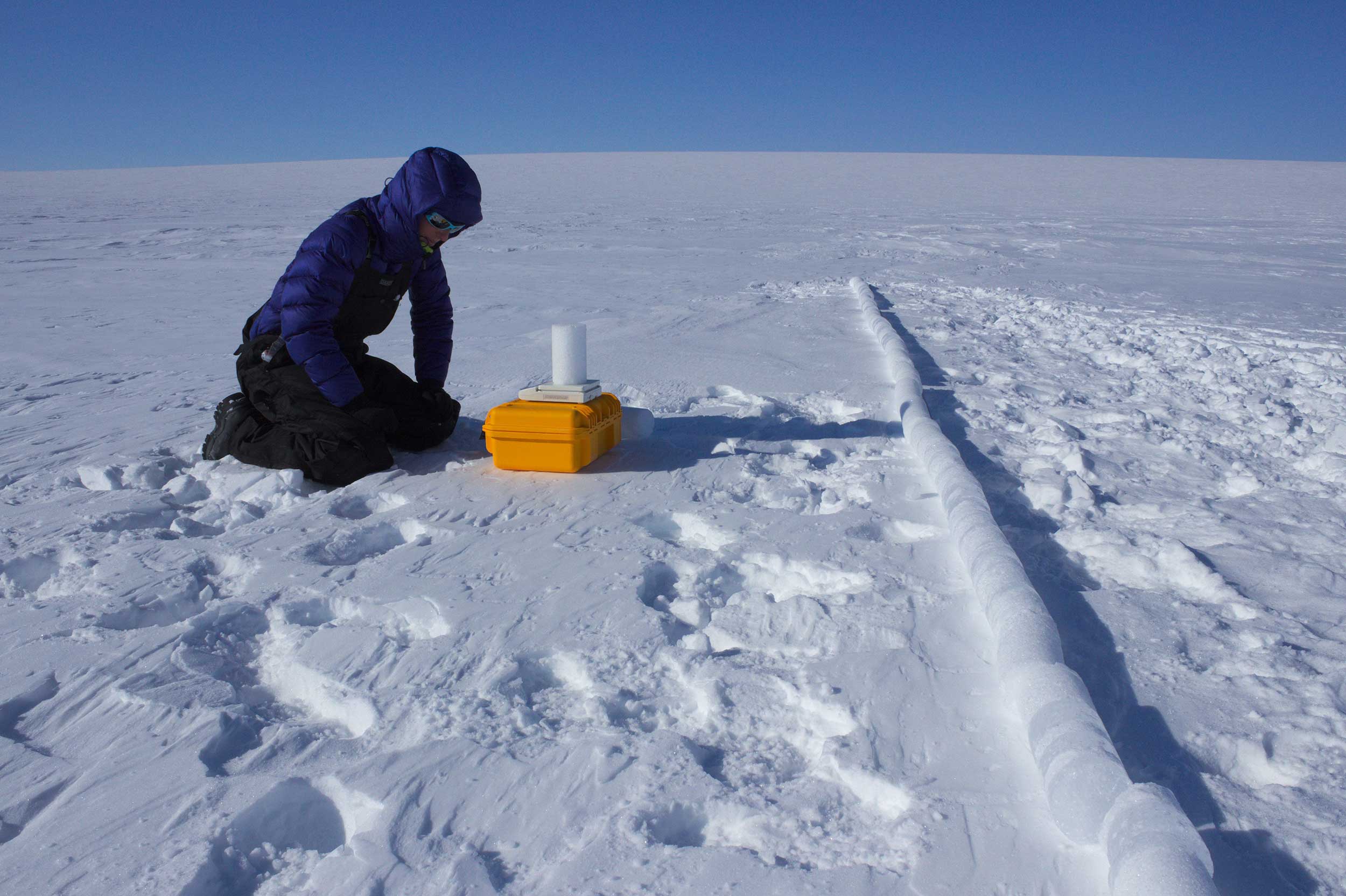

Ice core driller Ali Criscitiello examines a core sample. Photo courtesy Anja Rutihauser.

The goal of housing Canada's ice core collection at the University of Alberta and turning it into an accessible scientific resource is a big step closer to reality, thanks to a $2.3-million grant from the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Glaciologist Martin Sharp, Professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, has been working tirelessly for nearly two years to turn this vision into a reality, since the announcement that the former federal government wanted to find another home for the collection.

"By their nature, the ice cores are a diminishing resource-they are used up as they are analyzed, and the ice caps from which they were retrieved are now changing and shrinking rapidly," says Sharp. "The evidence of climate change is abundantly clear, and there isn't going to be a way to replace some of these cores." He notes one of the most dramatic examples of melting ice caps in the Canadian North, on Meighen Island, where 50 years of ice accumulation disappeared in less than three years. "This is about the most graphic example imaginable of how things have changed in the last decade."

"The evidence of climate change is abundantly clear. There isn't going to be a way to replace some of these ice cores." -Martin Sharp

Provided through the Exceptional Opportunities Fund, the grant (including operating funds) will facilitate the construction of a new facility for the ice cores-two walk-in freezers to house the thousand-plus metres of core and allow it to be characterized and sampled for analysis, plus an analytical laboratory that is expected to be completed in late 2016. Following that, the ice cores can begin the cross-country trek from their current home in Ottawa. Sharp is hopeful that the cores can be made available to researchers worldwide sometime in 2017.

Some of the surviving cores were drilled in the 1970s, with the most recent collected in the mid-2000s. In total, there is more than 1.4 kilometres of core, representing at least 10,000 years of ice accumulation and, in some cases, including remnants of ice from the last ice age.

Using the cores for research will require a delicate balance. "Ultimately, we want to see people using these materials, as a lot of analyses are possible now that were not possible when the cores were collected. The challenge is that if we use it all, there will be nothing left."

In addition to the challenges presented by climate change and rapidly melting ice, collecting new ice core samples is also extremely expensive. Sharp notes that it will be challenging to find resources to collect new cores, especially from the oldest ice found at the bottom of glaciers and ice caps, but he says there is an opportunity to partner with other coring groups in the world to collect cores and analyze samples in areas where the U of A has particular expertise.

"By their nature, the ice cores are a diminishing resource-they are used up as they are analyzed, and the ice caps from which they were retrieved are now changing and shrinking rapidly." -Martin Sharp

Whereas some analyses might once have required up to 300 millilitres of water from the core, researchers can now obtain the data they need from as little as a millilitre.

Helping answer critical climate change questions

Sharp notes that there are upwards of 10 world-class analytical labs on the U of A campus alone with interest in working on the ice cores, as well as researchers around the world who want to work on topics like the history of the atmospheric nitrogen cycle, organic contaminant and black carbon deposition in the Arctic, and reconstructing past variations of Arctic sea ice.

"Our goal is to create a national ice core facility that is open to all interested researchers, nationally and internationally," says Sharp. "We want people to come here to work with the material. We want them to generate and publish new results and then deposit the data in our archive for the benefit of all."

The timing couldn't be better as the U of A works to maintain its reputation for excellence in research on the Canadian North. Canada's cold regions are increasingly recognized for their valuable water, mineral and energy resources, and researchers from the university have spent decades getting to the bottom of what is happening at the top of the Earth. There is a renewed sense of focus with the recent launch of UAlberta North and the announcement that the U of A will lead the push for a new mountains-focused Network of Centres of Excellence.

"The University of Alberta is proud and honoured to be chosen as the new custodian of Canada's ice-core archive," says Lorne Babiuk, vice-president (research). "The cores are an invaluable research resource not only for Canada, but also for the world because of the information they contain-vital data to help advance knowledge in crucial areas such as climate change, the environment and even health via ancient microbes."

The facility will play a key role alongside our existing laboratories focused on the physical, chemical and microbiological analysis of snow, ice and permafrost, and provide access and vital data to the national and international research community. On behalf of the university, I thank CFI for this important research investment."