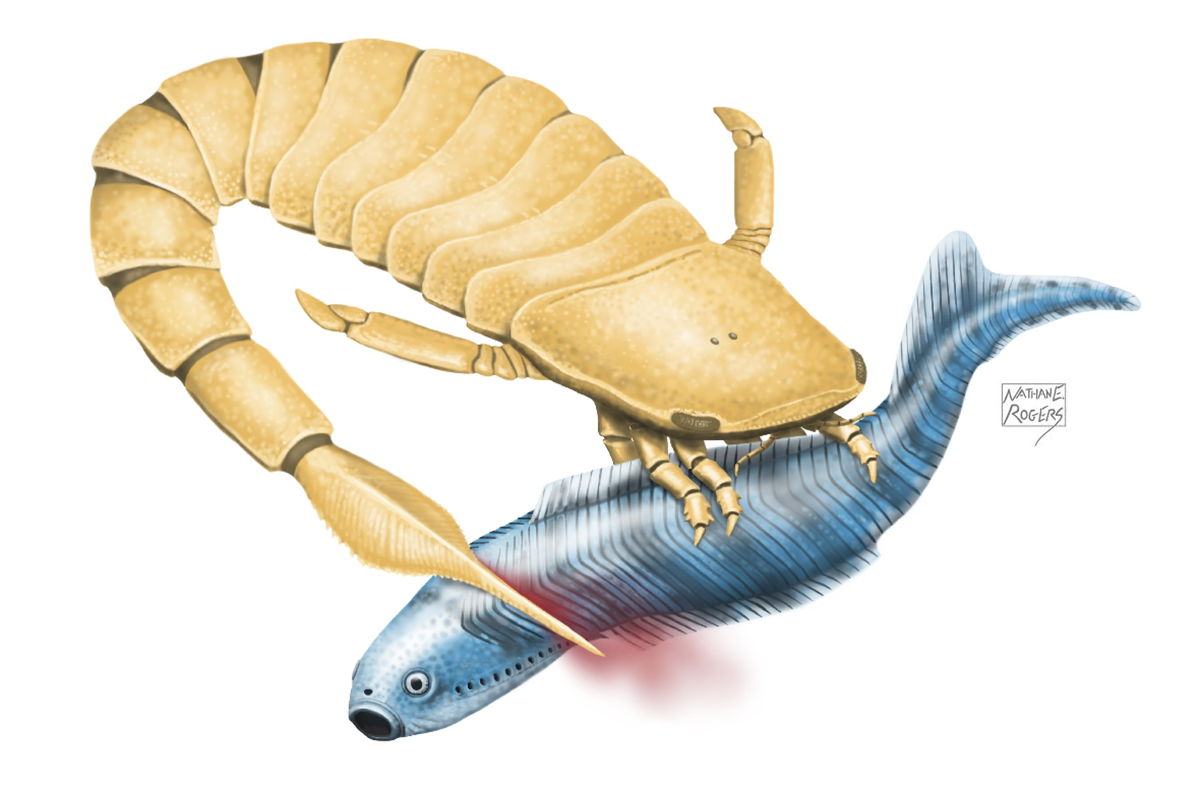

This illustration shows a sea scorpion attacking an early vertebrate. Credit: Nathan Rogers.

Four hundred and thirty million years ago, long before the evolution of barracudas or sharks, a different kind of predator stalked the primordial seas. The original sea monsters were eurypterids-better known as sea scorpions.

Related to both modern scorpions and horseshow crabs, sea scorpions had thin, flexible bodies. Some species also had pinching claws and could grow up to three metres in length. New research by University of Alberta scientists Scott Persons and John Acorn hypothesise that the sea scorpions had another weapon at their disposal: a serrated, slashing tail spine.

Armed and dangerous

"Our study suggests that sea scorpions used their tails, weaponized by their serrated spiny tips, to dispatch their prey," says Scott Persons, paleontologist and lead author on the study.

Sparked by the discovery of a new fossil specimen of the eurypterid Slimonia acuminata, Persons and Acorn make the biomechanical case that these sea scorpions attacked and killed their prey with sidelong strikes of their serrated tail.

The fossil, collected from the Patrick Burn Formation near Lesmahagow, Scotland, shows a eurypterid Slimonia acuminate, with a serrated-spine-tipped tail curved strongly to one side.

Powerful weapons

Unlike lobsters and shrimps, which can flip their broad tails up and down to help them swim, eurypterid tails were vertically inflexible but horizontally highly mobile.

"This means that these sea scorpions could slash their tails from side to side, meeting little hydraulic resistance and without propelling themselves away from an intended target," explains Persons. "Perhaps clutching their prey with their sharp front limbs eurypterids could kill pretty using a horizontal slashing motion."

Among the likely prey of Slimonia acuminata and other eurypterids were ancient early vertebrates.

The paper, "A sea scorpion's strike: New evidence of extreme lateral flexibility in the opisthoma of eurypterids," was published in The American Naturalist in April 2017.