Ukraine in Interwar Europe, 1921–1939

After the defeat of the 1917–20 struggle for Ukrainian independence, Ukrainians became the largest stateless nation in Europe. Ukrainian lands were partitioned among four states—the USSR, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. With this outcome, in the interwar period the Ukrainian question became the largest unresolved national question in Central and Eastern Europe, similar to the Polish question in the nineteenth century. Its possible solution potentially bore a strong impact on all of Europe, and, by implication, on what was then world politics. Above all, the Ukrainian question opened up great opportunities for all the countries interested in a revision of the Versailles system, first and foremost the USSR, Germany, and Hungary, but also, by the end of the 1930s, Italy and Poland. The Ukrainian question was also a concern for France and Great Britain. Both the government in exile of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) and Petliurist émigré circles placed their hopes on France, while the Western Ukrainian centrist political parties sought support from the British. During the 1920s the most influential groups were socialists and centrists. Other groups looked to the USSR until the outbreak of the Holodomor. Still others looked to fascist Italy and, after 1933 to Germany, as both models and tools to remedy the situation. In addition, the large Ukrainian communities in North America tried to influence U.S., Canadian, and British politicians and policymakers.

Despite these efforts, the Ukrainians were not a major actor in international politics, but were affected by the policies of numerous states. The only democratic state that supported the Ukrainian national movement in the 1920s was Czechoslovakia. Still, even that country’s policy did not include consistently supporting the Ukrainian national orientation among the indigenous Ukrainians in what was then called Subcarpathian Rus' (Carpatho-Ukraine). Poland, which had conquered the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic and undergone a decline in its democratic institutions, provided support only to the Petliurist community of émigrés from the UNR, Poland’s former ally. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, these Polish policies led to the so-called Volhynian experiment of limited support in that region for Ukrainian national goals in the hope of using the Ukrainian issue to undermine Poland’s archenemy, the Soviet Union. In the 1920s, during their policy of Ukrainization, the Soviet authorities planned to use the Ukrainian question to bring the “flame of the Communist revolution” into Central Europe, that is, by definition, into the heart of Europe. But apart from these pragmatic experiments, no interwar country supported the formation of an independent Ukrainian state comprising all Ukrainian ethnographic territories.

The countries that had considered playing the Ukrainian card stopped doing so when their calculations failed, and they became extremely hostile toward the Ukrainian national movement once it revealed its strength. The most egregious cases were Poland’s anti-Ukrainian mass repressions in the 1930s, the so-called Pacification and Revindication measures; the imposition of Romanian martial law and suppression of legal Ukrainian activities in Bukovyna; the Hungarian suppression of the new state of Carpatho-Ukraine in 1939; and, above all, the widespread Stalinist destruction of Ukrainian national elites in Soviet Ukraine—the so-called rozstriliane vidrodzhennia, or executed renaissance—and the genocidal famine of 1932–33. The international community’s and intellectual elites’ silence in response to Ukrainian appeals for aid and intervention during the Holodomor was an indication of the lack of support for Ukrainian aspirations.

All of the above repressions and the Western great powers’ surrender of Central and Eastern Europe to Nazi Germany left the Ukrainian question unresolved at the onset of the Second World War. Consequently, the Ukrainian question was ruthlessly manipulated by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. In the final result, Stalin overdid Hitler in playing the Ukrainian card. Through his victory in World War II and annexation of most of the Ukrainian ethnic territories, he brutally settled the Ukrainian question as an issue of geopolitics until independent Ukraine re-emerged with the collapse of the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the USSR.

There is a striking gap between the importance of the Ukrainian question in the interwar period on the one hand, and the scarcity of adequate academic attention to it on the other. Ukraine’s history during that period has been insufficiently researched, particularly in the context of European politics of the time. Although some subjects such as the situation of Soviet Ukraine, Poland’s policy toward Ukraine and Ukrainians, and German-Ukrainian relations have a considerable scholarly literature, much more remains to be investigated. The historiography of the Ukrainian question is rife with myths regarding Ukrainian internal politics and political thought as well as various states’ policies vis-à-vis Ukrainians and Ukraine. Important archival collections have not attracted sufficient scholarly attention, while documents that have been studied have been interpreted in accordance with generally accepted paradigms that frequently distort historical reality. Memoirs, diaries, and personal papers still remain unpublished, often in private collections,

With a view to overcoming these lacunae, historians Mirosław Czech, Ola Hnatiuk, and Yaroslav Hrytsak have initiated a long-term project on Ukraine in interwar Europe, consisting of a research program and a publication series, with the aim of stimulating a re-evaluation of the Ukrainian question. The main objective of the publication series is to make a wider source base available for studying the mostly neglected international dimension of the Ukrainian question during the years 1921–39. The goal of the research program is the development of new approaches to Ukraine’s political history during those years by placing it in the context of European history.

The project was launched in 2017. Both the publication series and the research project are components of the Ukraine in Interwar Europe scholarly program headed by Ola Hnatiuk at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. The project is supported by the Petro Jacyk Program for the Study of Modern Ukrainian History and Society at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the University of Alberta, in collaboration with the journal Ukraїna Moderna. Its academic board has included such internationally renowned scholars as Andrea Graziosi, Mark von Hagen (1954–2019), Ola Hnatiuk (chief scholarly editor), Yaroslav Hrytsak (director), Oleh Pavlyshyn, Serhii Plokhy, Frank Sysyn, Yuri Shapoval, Oleksandr Zaitsev, and Leonid Zashkilniak. Mirosław Czech is the program co-ordinator.

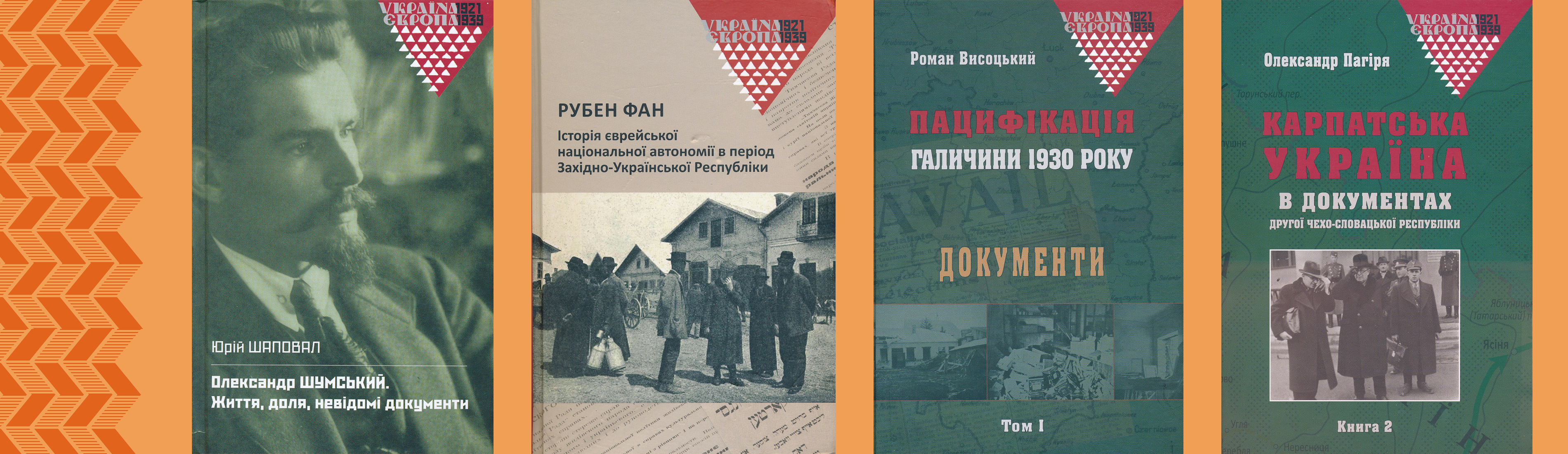

Every volume in the publication series contains extensive annotations and a comprehensive introduction. Several volumes have been published since 2017: documents about Oleksandr Shumsky, edited by Yuri Shapoval; the works and political essays of Olgerd Bochkovsky in three volumes (four books), edited by Mirosław Czech and Ola Hnatiuk; the first volume of documents on the Polish anti-Ukrainian Pacification campaign in interwar Poland, edited by Roman Wysocki; the first volume of documents on Carpatho-Ukraine, edited by Oleksandr Pahyria; and a Ukrainian translation of Ruben Fahn’s history of Jewish national autonomy in the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic, edited by Oleh Pavlyshyn. All of the volumes are distributed by CIUS Press, www.ciuspress.com.