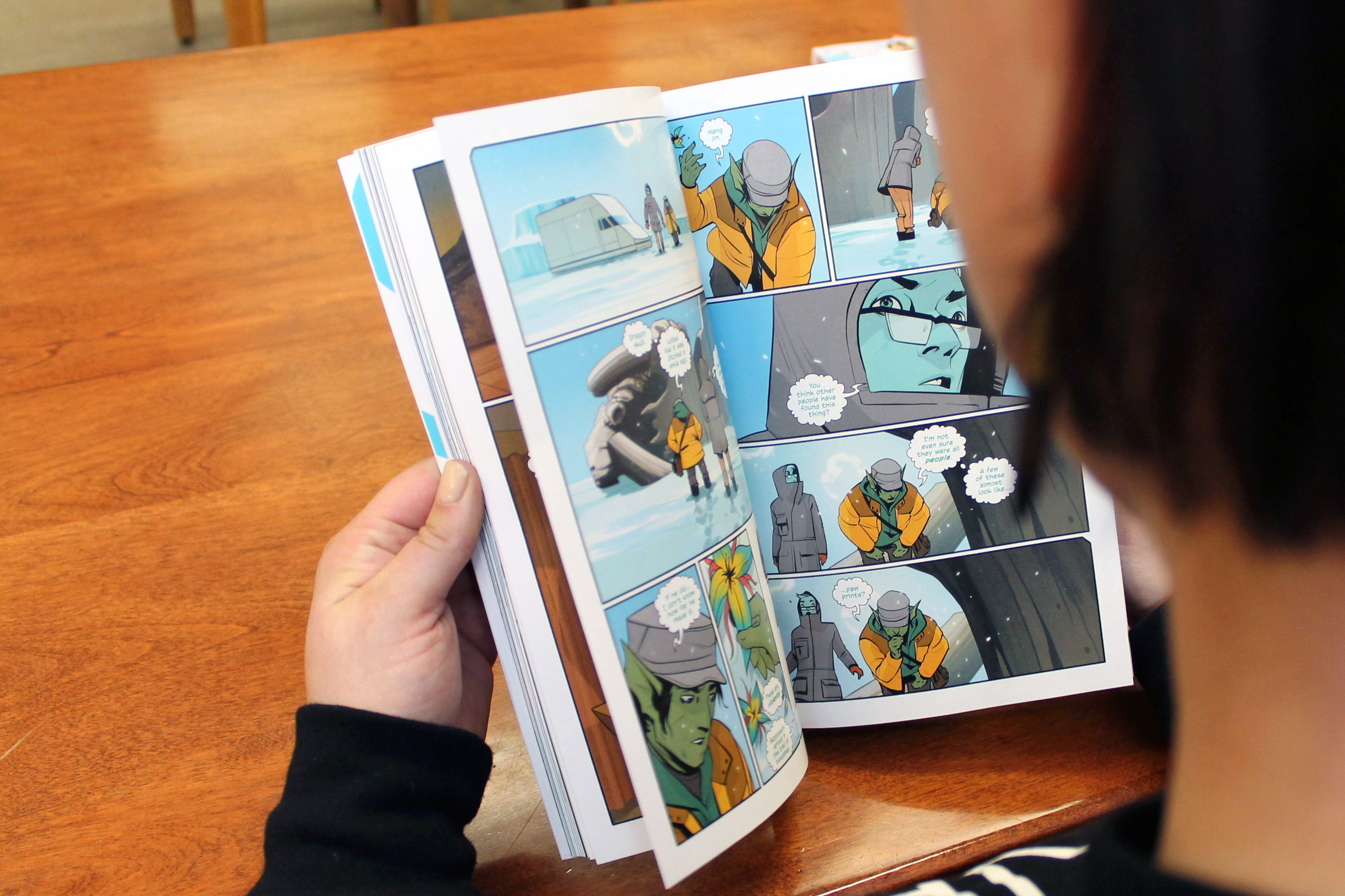

Once thought of as a niche medium appreciated mostly by stereotypical middle-aged comic book collectors like Comic Book Guy on The Simpsons, the graphic novel has been steadily moving from the fringes to the mainstream since the late 1980s.

In anticipation of Read in Week 2016, we sat down with Gail de Vos, professional storyteller and long-time sessional instructor at UAlberta’s School of Library and Information Studies, and David Lewkowich, assistant professor in the Department of Secondary Education, to talk about this relatively new hybrid of text and image and its value as a medium for teaching and research.

De Vos has taught a course focused on graphic novels since 2001. Her favourite character is Baba Yaga, a witch from Slavic European folklore who is depicted as a villain in the comic book series Hellboy. Lewkowich, whose research interests include literary theory, young adult literature and cultural studies, currently loves the character Marlys Mullen, created by cartoonist and author Lynda Barry, because Marlys is able to look through the complexity of her older sister’s experience and tell a joke.

Responses have been edited for length.

Faculty of Education: Why did you start integrating graphic novels into your teaching and research?

David Lewkowich: It is important to me, especially on the first day of class, to help my students understand and break down the view that the “teacher” has a wealth of knowledge. Instead, it’s about creating a relationship and space where the teacher is a beginner every day. I find that comics and graphic novels allow an avenue into this world view.

Comics and graphic novels make us all beginners. There is no one right way to read them, as no one has been formally schooled in how to read comics.

Gail de Vos: As a professional storyteller, I began reading graphic novels and comics because of my research into reworkings of folktales in pop culture. After reading a lot of them, I realized that they are the closest print medium to oral storytelling and folktales. I was truly captivated by this whole idea, which led to my research and teaching on the subject.

Faculty of Education: How does the medium help you interact with students?

Gail de Vos: I often think about the importance of self-interpretation, which is something David has hinted at earlier. This is all about learning to be confident—that there is no right or wrong way to read this. Once a book is in the public domain, the author and illustrator, or sometimes just the illustrator, no longer have control over how the book is read. It becomes about how the reader responds to the illustrations. I often start my courses off with wordless graphic novels, so that there are no words to show the readers where to go.

Often people don’t know how to start reading a graphic novel. They want a “how to read graphic novels” explanation because of their previous exposure to text-based books. This is especially true when you start reading wordless graphic novels.

David Lewkowich: I agree with Gail. There is something about how we have been schooled to read language in that we think that it’s a solid structure. There is something about the interaction of words and images, and images alone, that allows us to go more inside ourselves with our reading. It allows us to inspect the connections that we are making with the text.

Faculty of Education: What are the different themes that you seek to explore with students?

Gail de Vos: Self-discovery is a major theme that I’m interested in. It can be found in all forms of literature, and it’s a theme that is repeated over and over again in graphic novels.

David Lewkowich: I love graphic novels that tend to explore themes around love, adolescence and memory. These are all aspects of human existence, where it’s all about unanswerable questions and how can we allow the text to play with us.

I’m also interested in how our past experiences in school and our early experiences with teachers can impact a teacher’s future teaching. Words alone don’t seem to fully capture the emotional complexity of these ideas or themes.

Reading graphic novels allows us to explore our emotional past in a way that words can’t. I know that when I set foot back in a high school working as a teacher, I dealt with a lot of insomnia and my own emotional frustration, both of which I didn’t expect; I see that happening again when I look at my students. Working with graphic novels allows me to help support students in their own emotional discovery.

Faculty of Education: What advice do you have for educators, librarians and other information professionals looking to integrate graphic novels into their work?

Gail de Vos: Read them for yourselves. For every class I teach, regardless of the content, I put graphic novels on the reading list. I also suggest using wordless graphic novels so students take time to appreciate the illustrations themselves. It helps students become more observant.

David Lewkowich: Encourage students to dwell on the page. It can be hard to slow down on the page, but when you do, you notice things that you may have thought were only tangential. Sometimes it’s these tangential moments that can add a lot more to the text.

Comics create a level playing field and allow for discussion where no one possesses the knowledge as to what is the meaning of the text and everyone can come to their own conclusions.

The University of Alberta is proud to be a partner of Read In Week Edmonton 2016. The purpose of Read In Week is to create a greater awareness of the importance of reading. Historically, the event has successfully promoted the school as an important place for the development of lifelong literacy. Read In Week Edmonton runs from October 3-7, 2016. Visit the website for more information.