Jennifer Kelly was proud to have some of her research about black communities in Alberta on display at the legislature when the Alberta government officially recognized Black History Month at the beginning of February this year. But the University of Alberta Faculty of Education professor says it’s time to move black history from yearly observance to part of the national narrative.

“It would be essential to recognize that the African-Canadian community didn’t develop in isolation, but rather in relation to other social groups,” says Kelly.

Part of that effort, says the professor of educational policy studies, is bringing African-Canadian historical figures out of the shadow of their better-known American counterparts. She points to Viola Desmond, the Nova Scotia businesswoman and civil rights activist whose resistance to segregation in a movie theatre preceded by a decade Rosa Parks’s historic refusal to leave the whites-only section of a bus in Alabama.

“Desmond’s experience is less known, yet she stood up and refused to move before Rosa Parks did it in the States. So in many ways we have our own people who are just as worthy of learning from,” says Kelly.

Exhibiting Alberta’s black heritage

Desmond has already been commemorated on a postage stamp and will become the first Canadian woman to be featured on Canadian currency in 2018, but such evocations of African-Canadian historical figures are rare.

Kelly’s own research has focused on uncovering the history of black communities in Alberta, which she has distilled to 12 displays panels that describe three eras: racialization, from 1900 to 1920; community formation and citizenship, from 1921 to 1945; and immigration and social change, from 1945 to 1970.

While some of the desire for research grew out of Kelly’s involvement with AfroQuiz, an annual event organized by the Council of Canadians of African and Caribbean Heritage where youth test their knowledge of African-Canadian history in a quiz show format, Kelly says her work was spurred by a conspicuous lack of educational resources on the subject.

“When you say to educators, ‘Why is there nothing in your classrooms around African-Canadians?’, they say ‘It doesn’t exist’ or ‘We just don’t know where you would go for such information’”, Kelly says. “So, gathering and researching was really an attempt to provide information that teachers and others in the community could access.”

Alberta communities interwoven

The histories of communities like Amber Valley, Campsie, Junkins (now Wildwood) and Keystone (now Breton), which were largely founded by black settlers from the U.S., are part of the story Kelly tells. But she’s also interested in depicting how black communities existed and interacted within majority-white communities in the early 20th century.

One archival source Kelly cites is “Our Negro Citizens,” a weekly column that ran in two daily newspapers in Edmonton in the 1920s which served as both a society page and a chronicle of the community organizations and activities undertaken by black Albertans.

“The writer was Rev. George W. Slater, who was an African-American minister from the United States,” Kelly says. “He wrote the column, I think, as a counter-story to the traditional understandings of the black community as lacking in agency and as basically not contributing—so not being real citizens.”

“Edmonton did not have the huge community it has now, but they were a presence, in terms of what was happening, and how their lives interacted and engaged with the wider community.”

Many histories make one nation

Kelly wants the displays she created from her research to have an active existence and makes them available to teachers and community groups who want to use the content to discuss the history of African-Canadians in Alberta. She also used her research recently to make a case before an expert panel for including more black history as part of Alberta’s curriculum renewal, which is currently underway.

“One of my issues is to look at the ways in which history is constituted within a particular context—i.e. Canada—rather than looking at Canada as just being about two founding groups, French and English,” Kelly says. “I would argue we need to think more conceptually about how we teach histories and how communities make their lives in certain geographical spaces.”

Kelly’s research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and Canadian Heritage.

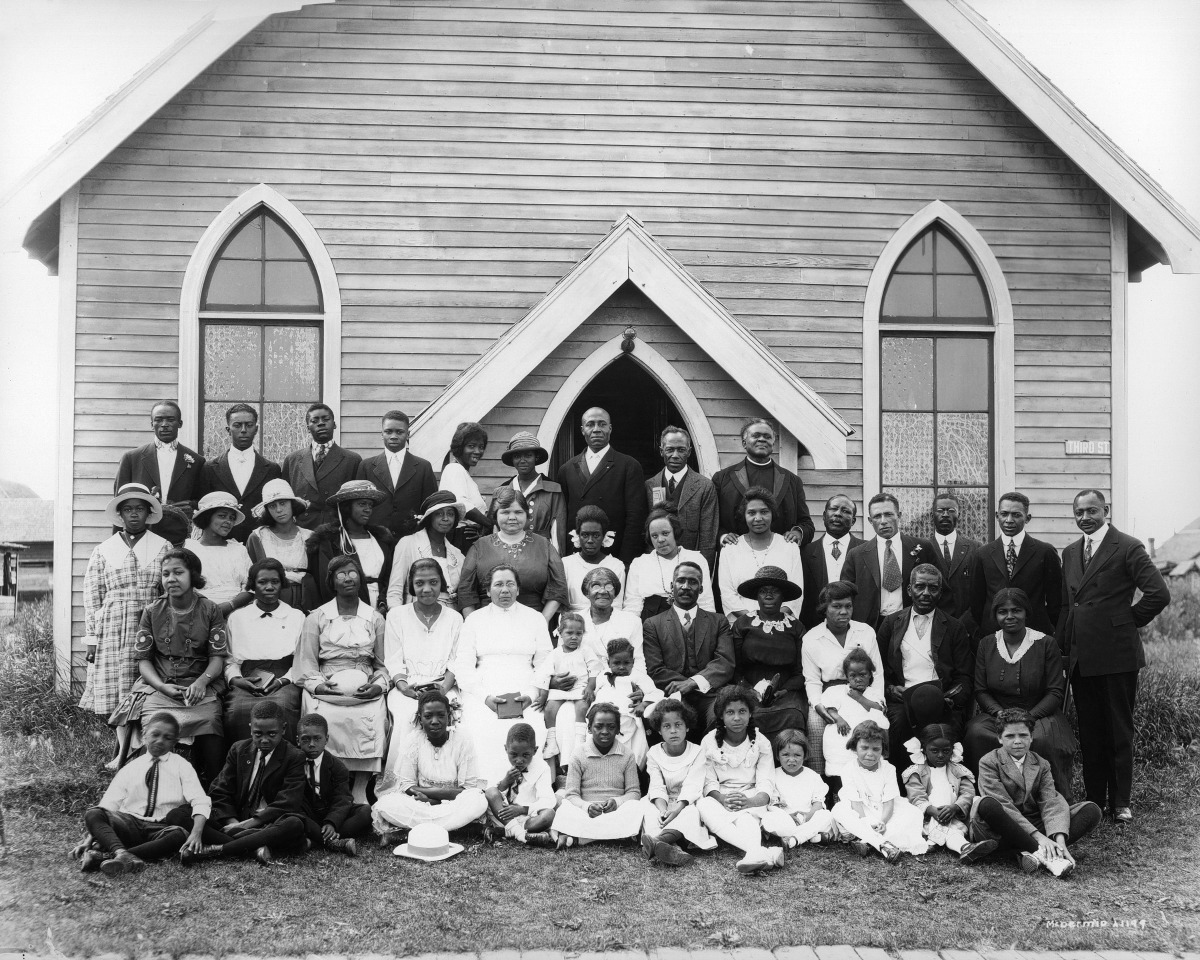

Feature image: Archival photograph of the Emanuel African Methodist Church congregation, early 1920s, Edmonton.