It’s an Unequal Day in the Neighbourhood!

Exploring the Link between Income Inequality and Maternal Mental Health in Calgary, Alberta

By: Sammy Lowe, MSc

September 23, 2021

Sammy Lowe is a former Graduate Research Assistant with the Centre for Healthy Communities. He is a recent graduate of the MSc in Epidemiology program with the School of Public Health, and has been nominated for the Dean's Gold Medal graduation award. He currently works with the CHEER and EMERGE research labs within the School of Public Health as a Project Coordinator and Research Associate, respectively. Outside of work Sammy enjoys all things theatre, knitting, and 1980s!

“What good does it do to treat people’s illnesses, to then send them back to the conditions that made them sick?” The Hon. Monique Bégin

How much money do you make? Do you make twice as much as I do? Half? No really, I’d like to know! Now, I recognize that this is a very personal and potentially awkward question, but I ask because your answer could have implications for our health and wellbeing.

Absolute income (i.e., the amount of income an individual possesses) has long been identified as a highly influential determinant of health. Those with less income are at risk of experiencing adverse health outcomes due to difficulties in securing basic needs (e.g., food, shelter), and accessing important healthcare and social services. Evidence from around the world has highlighted a clear gradient between levels of absolute income and health, where having lower income and wealth relates to poorer health outcomes.

Research into this association has revealed that our health might not only be shaped by how much income we have, but also by how much income we have relative to those around us. Such research has resulted in the emergence of the income inequality hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that the distribution of incomes within a given area (e.g., countries, provinces, cities, neighbourhoods) impacts our health through a variety of pathways. These pathways include stressful social comparisons and a breakdown of social cohesion and trust. The social determinants of health (SDOH) framework highlights income inequality as playing an important role in population health. The gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ continues to widen, particularly in the current COVID-19 pandemic (see the ‘k-shaped’ economic recovery for more information). With this growing gap, we may see an increase in a variety of adverse health outcomes, including heart disease, poor self-rated health, and shorter life expectancy.

A particular set of health outcomes that has been gaining traction in the income inequality literature is that of mental illness. In Canada, an estimated 1 in 5 people experience mental illness every year. Women bear a disproportionately high brunt of this mental health burden compared to men. Mothers, in particular, demonstrate especially high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. Unfortunately, very few studies to date account for this gender inequality.

To address this knowledge gap, I embarked on my thesis project to quantify and better understand the associations between income inequality and maternal mental health. To do so, I had access to incredibly rich data from the All Our Families (AOF) Study, an ongoing cohort based in Calgary, Alberta. The AOF cohort study takes a life course perspective, following mothers and their young children from mid-pregnancy to several years postpartum. A wide range of demographic, health, and social factors and outcomes are measured over the course of the study. Currently, the AOF has just completed an 8-year postpartum follow-up and is developing and administering COVID-19-specific surveys. I had access to AOF data ranging from 2008-2014 for the purposes of my thesis, which encompass six data collection points from approximately 25-weeks of pregnancy up to 3-years postpartum. After data linkage and cleaning, these data provided a relatively large sample of 2,461 mothers nested within 196 Calgary neighbourhoods.

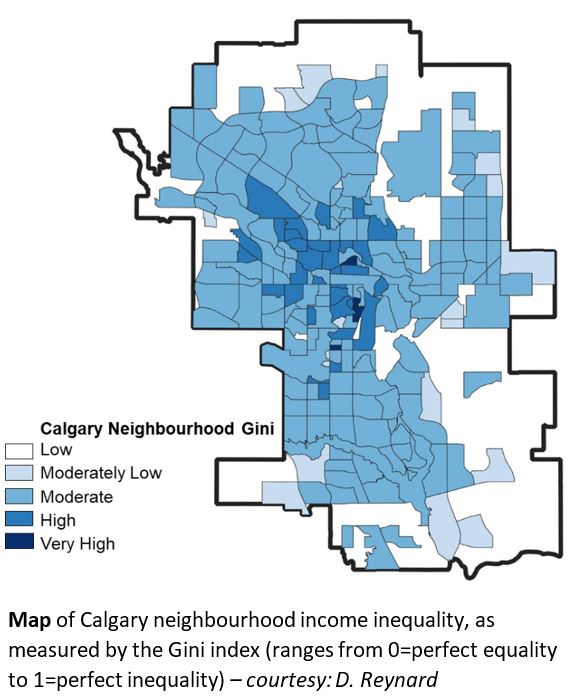

Specifically, I sought to determine if income inequality at the level of Calgary neighbourhoods was associated with changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms (see Map below). I used multilevel-modelling techniques to quantify these associations. For the non-statisticians in the crowd, this approach involved analysing the trends of the mothers’ mental health symptoms over time, while accounting for a variety of factors (e.g., household income, education, marital status), dynamic mental health trajectories, and clustering of AOF mothers within neighbourhoods.

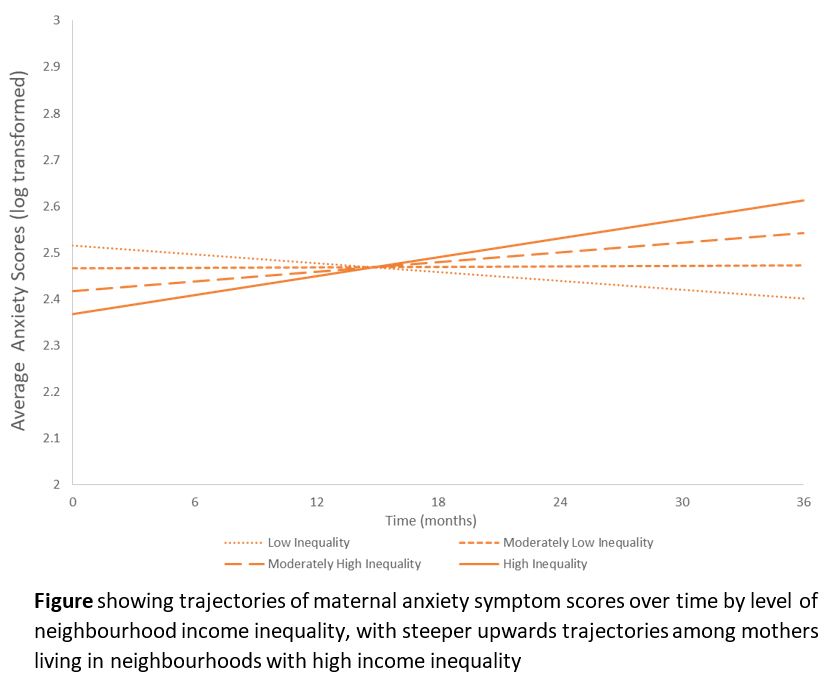

The results found that there was an excess rate of increase in average anxiety scores over time by increasing level of income inequality (see Figure below). This excess rate of increase means that over time, mothers who lived in neighbourhoods with greater income inequality experienced steeper upwards trajectories in anxiety symptoms compared to mothers from lower inequality neighbourhoods. Interestingly, I did not find significant associations between income inequality and depressive symptoms. The discrepancy in associations between anxiety and depressive symptoms could suggest that income inequality impacts these distinct mental health outcomes via different pathways. Additionally, when analyzing different levels of household income, I found that the association between higher inequality and an excess increase in anxiety symptoms over time did not differ between richer and poorer mothers. Thus, it is possible that income inequality presents a public health concern for all mothers regardless of their own individual wealth. More research is needed to better understand the role income inequality plays in shaping the mental health of different populations across Canada, such as other distinct and less well-studied target groups (e.g., LGBTQ2S+ communities, immigrants, houseless persons).

In terms of concrete next steps, the EMERGE Research Lab, led by Roman Pabayo (a CHC Scientist and the Health Equity Thematic Area Lead), is currently using work from this thesis as a foundation to explore the potential roles that social support and community engagement might play in the link between income inequality and maternal mental health. They are also investigating whether interventions aimed at reducing income inequality, such as provincial minimum wage increases, also have benefits for maternal mental health.

Ultimately, I hope this work highlights that social and structural relative inequalities do in fact exist within a Canadian context and have implications for our collective health and wellbeing. By identifying, understanding, and prioritizing income inequality and other SDOH, we can address public health issues in a more holistic and equitable way.

So, when I’m asking you if you make more money than I do, I’m not trying to be rude. I’m asking because I care about your health!

Acknowledgements:

The author acknowledges the contribution and support of AOF participants and AOF team members. Suzanne Tough is the Principal Investigator of the AOF study. This research has been funded by the generosity of the Stollery Children’s Hospital Foundation and supporters of the Lois Hole Hospital for Women through the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute, as well as the MSI Foundation (grant number 896).