It's a dark and frigid February evening as I scurry across the icy parking lot at University of Alberta Hospital (UAH), enroute to an evening interview.

Inside the front door I take the escalator to the second floor, then turn left and follow the signs to the Eating Disorder Program. All is quiet tonight, and the hallways are almost empty.

The unit entrance door is locked so I ring the buzzer. After waiting for a couple of minutes, I debate whether to ring it again. Finally, I do. This time a smiling young woman emerges.

"She asked me to come out and get you," she says with a conspiratorial grin, as if addressing a lost puppy. "She's waiting in her office. It's at the end of the hallway."

Dr. Lara Ostolosky peeks out her door, and motions me in. She has agreed to do this interview tonight because there was no other time she could fit me into her hectic workday. Little wonder.

For seven days a week - including holidays - and 12 to 14 hours every day, the Eating Disorders Program buzzes with activity. Roughly 60 patients attend the program each day, as day patients or inpatients.

The vast majority are young females in their teens and 20s, although it's not unusual for young men to get treated here as well.

"A few years back we used to see people from 14 years of age and up. But over the past few years patients are coming in younger and younger, some as early as age 11. I even had one 10-year-old," says Ostolosky.

Since eating disorders like Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa are often lifelong conditions, there is no limit on how old a patient might be. Nor is there a cap on how many times a person can be treated. Relapses are common, so some patients return for "tune ups" several times.

"Once a patient is seen in our program we'll continue to see them indefinitely. They are always welcome back," says Ostolosky. "We have patients that we have seen for years, and data going back many years on people, including all the dieticians' data."

Dr. Henry Piktel, a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry since 1979, launched the program in the early 1990s. Ostolosky, an Assistant Clinical Professor in the Psychiatry Department, came on board in 2004.

From humble beginnings, the Eating Disorders Program has grown into the largest program of its kind in Western Canada. Its dedicated team of more than 30 staff includes two psychiatrists, five dieticians, five psychologists, a recreational therapist, 20 nurses, three unit clerks and a unit manager.

The demand for treatment is enormous, and seemingly endless. When I ask Ostolosky how many patients she has treated here, she reaches into a drawer, and pulls out a thick stack of papers. She plops it on her desk with a thud. "This is my patient list alone. I'd say that's a thousand names or more, past and present, Dr. Piktel has been in practice twice as long as I have, so the full list would be in the thousands," she says. "The number of referrals we get are just ridiculous."

It's a big load to carry, particularly since Piktel is approaching the end of his long and distinguished career. But Ostolosky remains deeply committed to the young patients she serves and is obviously touched by the life-and-death struggles so many of them face.

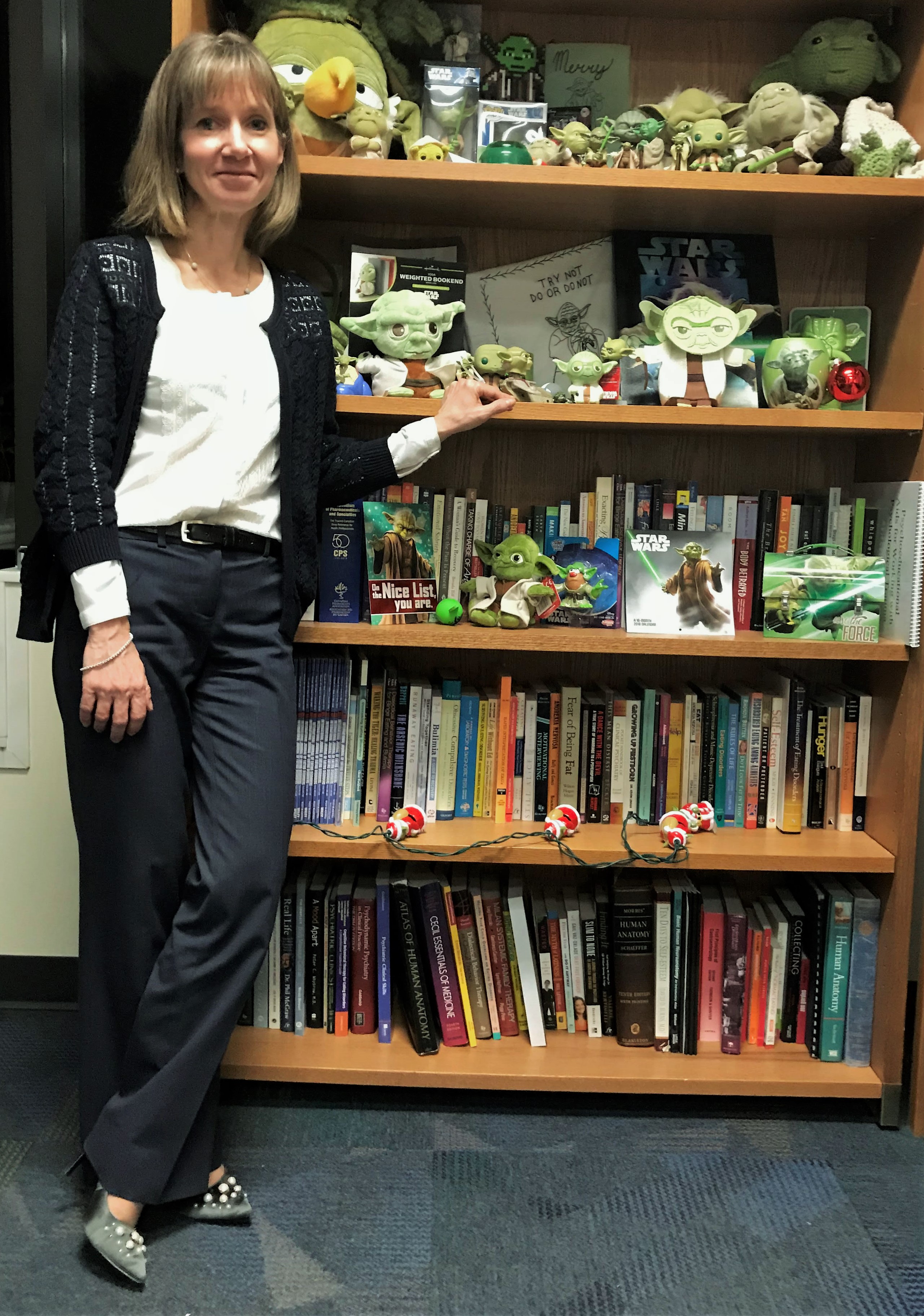

The growing collection of Yoda figures that fill a bookshelf in her office reflects the emotional bond she has with her patients. "A patient gave it to me because they thought I was wise, and it grew from there," she says. "I'm not really a Star Wars fan at all but Yoda is kind of endearing."

Levity is a rarity for those who suffer from Anorexia Nervosa, which afflicts 0.5 per cent of the general population. Studies show it has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder. As many as one in five with chronic Anorexia die from the effects of the illness, either through malnutrition or suicide.

So what accounts for the growing numbers of patients who suffer from this alarming illness? Well, it's complicated. Environmental factors and genetics both play a role, says Ostolosky.

"When I was young, the stresses were there in junior high and in high school. But I think the expectations for kids and young adults are a lot higher now. To stay on the straight and narrow, kids need a lot of support," she says.

"And I definitely think genetics is a huge thing as well. Anorexia is somewhat predetermined, although not always. I'm always amazed when I do an interview with a patient, almost every time - whether it be Anorexia or Bulimia - there is a family member who has it, a cousin or a grandmother or whatever."

Since the Eating Disorders Program views eating disorders as a brain-based illness, it employs multiple therapeutic tools and strategies to help patients normalize their eating habits, restore body weight, and most critically, address the distorted thought patterns that compel them to engage in self-destructive behaviours.

"With eating disordered girls it's not just a phase. They really are ill. The development of body image in the brain is a very complex thing. If any one of these processes is dysregulated, you end up with this distorted image of yourself. It's very much like schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is not caused by any external factor, it's predetermined," she notes.

"So a lot of cognitive work is done on the patients, in terms of building flexibility in their rigid thought patterns and learning emotional regulation skills. We use DBT (Dialectical Behaviour Therapy), CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), Psychodynamic Therapy, and the Maudsley approach to refeeding," Ostolosky explains.

The latter engages the patient's parents, who, with support and guidance from the Eating Disorders Program, are assigned the responsibility of "refeeding" the child at home. "It's a scary thing when your child is starving and you see them shrinking and you don't know what to do. So we want to empower the parents to be parents in this area," she says.

"I also want to get pet therapy and recreational therapy, so we can really give our patients the best possible chance to get healthy. We have a very cohesive team that thinks outside the box. Yes, we follow clinical practice guidelines but we do a lot of extras too," she says.

"The dieticians are always creating new things, so we have a lunch group and patients learn how to cook. We have a food science program where kids can get credit from their high school. It's all self-driven, nobody tells us to do these things. We think of these things and implement them as pilot projects. And if they work we keep them going."

Inpatients can attend daytime classes at the Stollery School, located within the nearby Stollery Children's Hospital, so their education doesn't suffer while they're in treatment.

"Our teachers are very dedicated and they liaise with the child's regular school. We keep the child going in their courses so they don't get behind. They have school blocks like regular school. They come back for their lunch and the teachers supervise them after lunch or breakfast so they don't go off and escape on us."

The "success rate" for patients - defined as those who are able to function normally after being treated - is at least 50 per cent, says Ostolosky. That makes it the most successful program of its kind in North America. But not all patients succeed. Some young lives end tragically.

"We've had some suicides. They are very difficult. You always think you could have done more, or you wish you could have done more, but realistically, things happen and you can't always foresee them coming," she says.

"Our death risk is very low, actually. We're hyper-vigilant. I know what's happening with my patients all the time. We are getting better at being very cognizant of the patient's mood. That is always on our minds, so we pay very close attention to that."

As for Ostolosky's long-term vision for the Eating Disorders Program, she has a ready answer. It's obviously something about which she has given considerable thought.

"The very first thing is we'd really like to accelerate our research. We have a very good database from the 20-plus years this program has been in existence, so there is a great deal of opportunity for research. It's something we're really wanting to facilitate amongst the psychologists, dieticians, and any others that care to do research with us," she says.

"We'd also like to have a clinical fellowship program here. We think we have a lot to teach individuals trying to work with this population. Most of the people who come here - whether they're dietician residents, psychology residents or psychiatric residents, have a very good experience," she adds.

"And in terms of patient care, what we want to do is expand outpatient programming to reduce hospital dependence. We'd like to see more groups and more help outside of the hospital setting so people don't lose sight of what's happening in their life by being in the hospital all the time."

Inside the front door I take the escalator to the second floor, then turn left and follow the signs to the Eating Disorder Program. All is quiet tonight, and the hallways are almost empty.

The unit entrance door is locked so I ring the buzzer. After waiting for a couple of minutes, I debate whether to ring it again. Finally, I do. This time a smiling young woman emerges.

"She asked me to come out and get you," she says with a conspiratorial grin, as if addressing a lost puppy. "She's waiting in her office. It's at the end of the hallway."

Dr. Lara Ostolosky peeks out her door, and motions me in. She has agreed to do this interview tonight because there was no other time she could fit me into her hectic workday. Little wonder.

For seven days a week - including holidays - and 12 to 14 hours every day, the Eating Disorders Program buzzes with activity. Roughly 60 patients attend the program each day, as day patients or inpatients.

The vast majority are young females in their teens and 20s, although it's not unusual for young men to get treated here as well.

"A few years back we used to see people from 14 years of age and up. But over the past few years patients are coming in younger and younger, some as early as age 11. I even had one 10-year-old," says Ostolosky.

Since eating disorders like Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa are often lifelong conditions, there is no limit on how old a patient might be. Nor is there a cap on how many times a person can be treated. Relapses are common, so some patients return for "tune ups" several times.

"Once a patient is seen in our program we'll continue to see them indefinitely. They are always welcome back," says Ostolosky. "We have patients that we have seen for years, and data going back many years on people, including all the dieticians' data."

Dr. Henry Piktel, a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry since 1979, launched the program in the early 1990s. Ostolosky, an Assistant Clinical Professor in the Psychiatry Department, came on board in 2004.

From humble beginnings, the Eating Disorders Program has grown into the largest program of its kind in Western Canada. Its dedicated team of more than 30 staff includes two psychiatrists, five dieticians, five psychologists, a recreational therapist, 20 nurses, three unit clerks and a unit manager.

The demand for treatment is enormous, and seemingly endless. When I ask Ostolosky how many patients she has treated here, she reaches into a drawer, and pulls out a thick stack of papers. She plops it on her desk with a thud. "This is my patient list alone. I'd say that's a thousand names or more, past and present, Dr. Piktel has been in practice twice as long as I have, so the full list would be in the thousands," she says. "The number of referrals we get are just ridiculous."

It's a big load to carry, particularly since Piktel is approaching the end of his long and distinguished career. But Ostolosky remains deeply committed to the young patients she serves and is obviously touched by the life-and-death struggles so many of them face.

The growing collection of Yoda figures that fill a bookshelf in her office reflects the emotional bond she has with her patients. "A patient gave it to me because they thought I was wise, and it grew from there," she says. "I'm not really a Star Wars fan at all but Yoda is kind of endearing."

Levity is a rarity for those who suffer from Anorexia Nervosa, which afflicts 0.5 per cent of the general population. Studies show it has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder. As many as one in five with chronic Anorexia die from the effects of the illness, either through malnutrition or suicide.

So what accounts for the growing numbers of patients who suffer from this alarming illness? Well, it's complicated. Environmental factors and genetics both play a role, says Ostolosky.

"When I was young, the stresses were there in junior high and in high school. But I think the expectations for kids and young adults are a lot higher now. To stay on the straight and narrow, kids need a lot of support," she says.

"And I definitely think genetics is a huge thing as well. Anorexia is somewhat predetermined, although not always. I'm always amazed when I do an interview with a patient, almost every time - whether it be Anorexia or Bulimia - there is a family member who has it, a cousin or a grandmother or whatever."

Since the Eating Disorders Program views eating disorders as a brain-based illness, it employs multiple therapeutic tools and strategies to help patients normalize their eating habits, restore body weight, and most critically, address the distorted thought patterns that compel them to engage in self-destructive behaviours.

"With eating disordered girls it's not just a phase. They really are ill. The development of body image in the brain is a very complex thing. If any one of these processes is dysregulated, you end up with this distorted image of yourself. It's very much like schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is not caused by any external factor, it's predetermined," she notes.

"So a lot of cognitive work is done on the patients, in terms of building flexibility in their rigid thought patterns and learning emotional regulation skills. We use DBT (Dialectical Behaviour Therapy), CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), Psychodynamic Therapy, and the Maudsley approach to refeeding," Ostolosky explains.

The latter engages the patient's parents, who, with support and guidance from the Eating Disorders Program, are assigned the responsibility of "refeeding" the child at home. "It's a scary thing when your child is starving and you see them shrinking and you don't know what to do. So we want to empower the parents to be parents in this area," she says.

"I also want to get pet therapy and recreational therapy, so we can really give our patients the best possible chance to get healthy. We have a very cohesive team that thinks outside the box. Yes, we follow clinical practice guidelines but we do a lot of extras too," she says.

"The dieticians are always creating new things, so we have a lunch group and patients learn how to cook. We have a food science program where kids can get credit from their high school. It's all self-driven, nobody tells us to do these things. We think of these things and implement them as pilot projects. And if they work we keep them going."

Inpatients can attend daytime classes at the Stollery School, located within the nearby Stollery Children's Hospital, so their education doesn't suffer while they're in treatment.

"Our teachers are very dedicated and they liaise with the child's regular school. We keep the child going in their courses so they don't get behind. They have school blocks like regular school. They come back for their lunch and the teachers supervise them after lunch or breakfast so they don't go off and escape on us."

The "success rate" for patients - defined as those who are able to function normally after being treated - is at least 50 per cent, says Ostolosky. That makes it the most successful program of its kind in North America. But not all patients succeed. Some young lives end tragically.

"We've had some suicides. They are very difficult. You always think you could have done more, or you wish you could have done more, but realistically, things happen and you can't always foresee them coming," she says.

"Our death risk is very low, actually. We're hyper-vigilant. I know what's happening with my patients all the time. We are getting better at being very cognizant of the patient's mood. That is always on our minds, so we pay very close attention to that."

As for Ostolosky's long-term vision for the Eating Disorders Program, she has a ready answer. It's obviously something about which she has given considerable thought.

"The very first thing is we'd really like to accelerate our research. We have a very good database from the 20-plus years this program has been in existence, so there is a great deal of opportunity for research. It's something we're really wanting to facilitate amongst the psychologists, dieticians, and any others that care to do research with us," she says.

"We'd also like to have a clinical fellowship program here. We think we have a lot to teach individuals trying to work with this population. Most of the people who come here - whether they're dietician residents, psychology residents or psychiatric residents, have a very good experience," she adds.

"And in terms of patient care, what we want to do is expand outpatient programming to reduce hospital dependence. We'd like to see more groups and more help outside of the hospital setting so people don't lose sight of what's happening in their life by being in the hospital all the time."