Since the earliest days of computers, we've thought of them only as number-crunching machines, reliant on codes of zeros and ones.

"All of the early computer people were mathematicians," says Harvey Quamen, associate professor in the Department of English & Film Studies. "So when they wanted to describe how these weird, alien machines worked, they grabbed a system that made sense to them, which was numbers."

But computer code is based on logic and needn't be numerically based. As the famous mathematician Danny Hillis argues in The Pattern on the Stone, a zero and one are not inherently better than an X and Y. "The zeros and ones are just metaphor, actually," says Quamen.

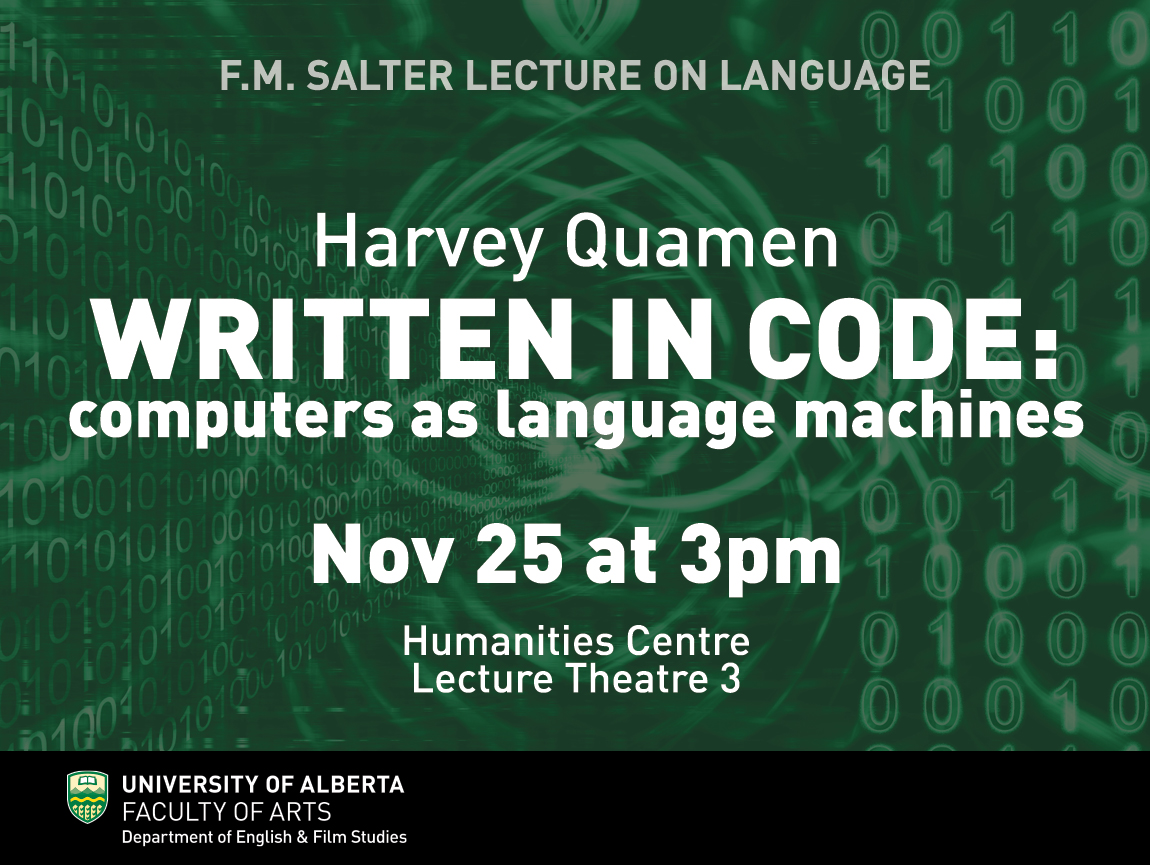

In his upcoming talk on November 25, titled "Written in Code: Computers as Language Machines," he'll explore what it could mean for computers to communicate via language. Along the way, Quamen will explore the history of computing, including pivotal figures like Ada Lovelace who, in the 1830s, created the world's first computer program. "The English department will know her mostly by her father, the English romantic poet Lord Byron," he says.

Quamen will also examine the role of Alan Turing, the famous mathematician and computer programmer (and subject of the Hollywood film The Imitation Game). In the 1950s, Turing wrote a number of groundbreaking articles exploring how computers could potentially understand human language and become intelligent.

"A lot of people assumed that a computer could only have the knowledge inside it that we would give it - like a library card catalogue," says Quamen. "But Turing said we could treat the computer differently, as if it was a child, so it could learn things on its own."

Machine learning was a radical idea in Turing's time, when there existed a half-dozen computers in the entire world. But today, we see examples everywhere - from Amazon to Netflix to the iPhone's voice-activated assistant, Siri.

But while the technology is accepted as a useful tool in day-to-day life, there's some resistance among humanities scholars. As an academic working within the realm of digital humanities, a field that blends both areas of study, Quamen would like to see more academics embrace technology.

He explains that computers can help analyse the written word in new and surprising ways. Analytical techniques can provide clues about specific texts and time periods, but also how human beings write and read in the modern age.

"We need humanism 2.0 and we can't keep rejecting technology out of hand," he says. "Not because technology is inevitable, but because we need to adjust our world view."

The F.M. Salter Lecture on Language was established in 1988, in commemoration of U of A Professor Frederick M. Salter (1895-1962), a former Cape Breton coal miner, author and scholar. He established this country's first creative writing course in 1939 and went on to teach such luminaries as Rudy Wiebe, who delivered the Salter Lectures in 1992, and WO Mitchell. In 2005, FM Salter was named one of the 100 Edmontonians of the Century (formal recognition of Edmontonians who have made a significant impact on the development of Edmonton as a community).

Event information:

Date: Nov. 25

Time: 3 p.m.

Lecture location: L-3 Humanities Centre/reception (reception on west foyer of the third floor)