Q: Why are we now, in 2017, officially recognizing Black History Month in Alberta?

A: This year, MLA David Shepherd raised the issue with the provincial government to officially recognize it at the legislature. Also, it dovetails with theUnited Nations International Decade for People of African Descent, and so it seemed a good time to bring those two things together. This, in some ways, is an opportunity to educate about the diversity and heterogeneity of the communities that fall under the umbrella of "black." I'm pleased that the provincial government is taking - in my view - this long overdue move.

This is also Canada's 150th. It bears noting that much of the land that was given to Americans or blacks coming in was Indigenous land. So I find a lot of black Canadians thinking about their relationship to Indigenous peoples, to dispossession. This recognition, in this year, is poignant.

Q: Why is it important that we officially recognize black history in Alberta?

A: We've usually framed it in terms of multiculturalism, like you see at Heritage Days or CariWest, but we haven't recognized the great Albertans who have contributed to public life. In some ways, black Canadians get subsumed or obscured by the experiences in the United States.

And there are significant differences and similarities between the two, including in terms of composition. African Americans are American-born, mostly, but Canadians are primarily three clusters of people: those who have been here for some time, and like many Canadians, are three-generations traceable; those of Caribbean descent; and then, Africa. When we are elsewhere, such as Africa, we are Igbo or Ndebele; or if you're from the Caribbean, you're Jamaican or from the Bahamas or Barbados; but in North America we are all the same thing - black. That blackness bridges national, cultural and linguistic differences. It's this tyranny of homogenization, which obscures individuality, heterogeneity and so on. Black History Month can tease out these details.

Some studiously resist the idea of "blackness," which is shaped by a history of slavery and degradation and focus on African descent or African diaspora or African Caribbean, and [they] would rather focus on the national or cultural component of blackness. All of those concepts co-mingle uncomfortably in the North American space, so we need Black History Month to recognize this rich, Canadian-based heritage.

But also specifically, in Alberta, we don't know the history. Whether it's people like the black heritage pioneer group that came from Oklahoma and elsewhere and settled in Amber Valley or the all-black Toles School, which is replicated in the Canadian Museum of History. There was segregation right up to the 1970s. Edmonton had segregated pools, segregated schools. The KKK was active into the 80s.

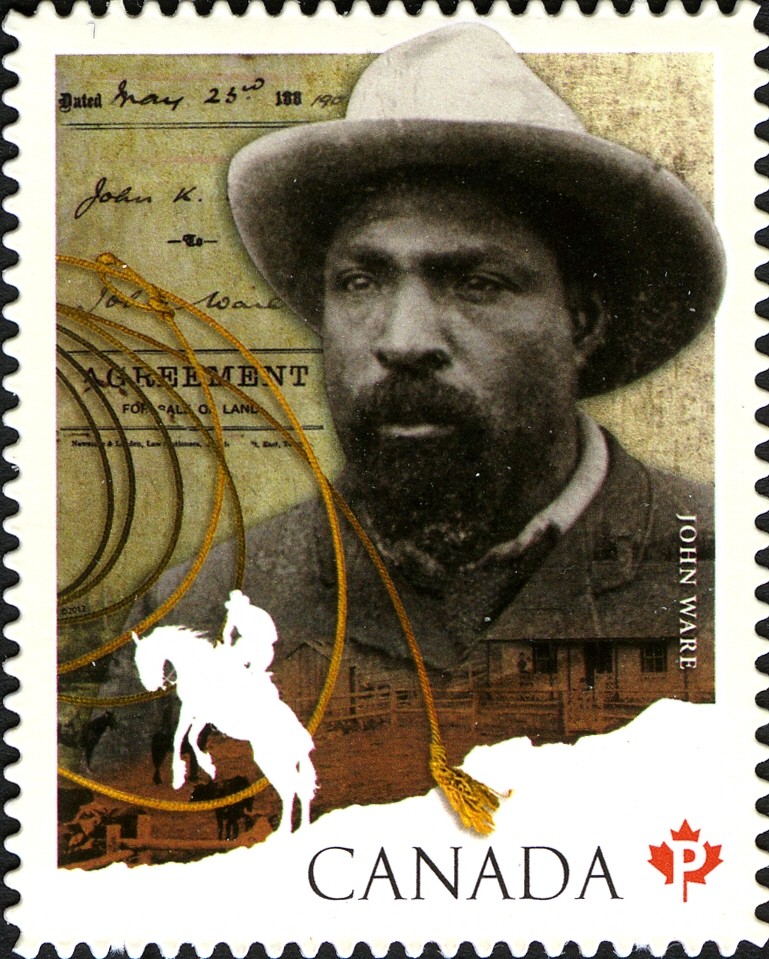

We have obscured this history in Alberta and we don't talk about our deep history of racism. The well-known black cowboyJohn Ware, after whom there is Ware Creek and Ware Ridge, and [there is] even a section of a national park named after this black cowboy. And yet the early name for John Ware was "Nigger John," and that tells you the shared kind of discourse between the US and Canada at the time. There was anall-black baseball team - not known. But also the blacks who have been judges, mayors, those who have contributed to political life but are not well-known, or those who likeFil Fraser who was on the Spicer Commission, who was the founding chair of the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards. More recently, there is the accomplished Violet KingHenry, a graduate of the University of Alberta who went on to become the first black woman lawyer in Canada. This is not known. It begs the question: why?

Q: How marginalized is black history in Canada?

A: Black folks are at once and at the same time hyper-visible and yet invisible. There are some notable figures, fromMichaëlle Jean, the first black governor general of Canada, toJean Augustine who was the first black woman elected federally. Most people are more likely to know Rosa Parks, althoughViola Desmond was a decade before Rosa Parks. We hear about the Underground Railroad, which tends to be the iconic story of Canada, but as the writer Lawrence Hill correctly points out, in many ways this experience tends to drown out the other, everyday experiences of racism and racial biases that many black folk experience.

There is also the "borrowed blackness" - or as I prefer, "borrowed experiences" - of people who, when they think about black people, are using information from television or American news. These are not the everyday lived experiences with black Canadians. And so in some ways, they project that onto us, which obscures what's actually here.

Q: Is there a particular Alberta story that resonates for you?

A: Less is known about the early contributions of black women. One fascinating story is of a woman known as "Auntie," later identified as Annie Saunders, who lived in Pincher Creek in the 1890s. The Calgary writerCheryl Foggo traced Auntie's story, and the archival records show she worked for Colonel James J. Macleod, after whom the town is named. After she left the Macleod family, she became quite the entrepreneur, running three businesses, including a boarding home, laundry and restaurant.

I worked on a SSHRC-funded project with [Education professor] JenniferKelly where we looked at racialization, immigration and citizenship in Canada. We wanted to focus on Western Canada, precisely because so many of the stories told are about Central and Eastern Canada. We had these archival photographs and we had to try to identify and connect who these people were, because they would just be "Nigger Annie" or "Nigger John." And then, as history moved on, they became Annie Saunders and John Ware. Although Annie exemplifies the idea of Alberta's entrepreneurial spirit, as Foggo put it, she's not known to most Albertans.

As a consequence of not knowing that history, when you talk about challenges, there is a tendency to disbelieve. It's a challenge to have our voices heard, still.

Q: What are some of the activities and events around Black History Month in Alberta?

A: There is theAfroQuiz - a major event put on by the Council of Canadians of African and Caribbean Heritage. There are church ceremonies, with various speakers who come in from all over. The community has always celebrated Black History Month because it presented an opportunity for people to get together and get to know each other and the different journeys that we have taken to get to Alberta. But as this year will mark, we too are learning about the history, 1900s and earlier.

Q: What does this official recognition of Black History Month mean to you personally?

A: I think it's important. It renders visible for Albertans and Canadians what is often invisibilized. We are the third largest "visible minority" in Canada, next to the Chinese and South Asians. Calgary has the fourth largest population, and Edmonton, the fifth. There's a tendency to borrow blackness from the United States - to project onto us their experiences. And yet when you look the Statistics Canada data, the black population is highly educated, but underemployed.

I've spent overtwo decades at the university talking about equity and inclusion, and dealing with issues around unconscious or implicit biases. For me, it helps to focus attention on these kinds of issues. To say, it matters, or it should matter. What is the assumption being made that renders black folk invisible, despite the high level of education, these diverse contributions? For me personally, I hope this official recognition at the Alberta legislature makes these experiences - this history - visible, and allows us to talk about them in constructive ways.

Q: In your opinion, what else needs to be done?

A: I have called for a royal commission on visible minorities. There are about nine groups within that large category and we all have diverse experiences. Again, that concept - visible minority - obscures the complexity. These stories need to be desegregated and told so that you can get at the rich sense of these various groups' contributions to Canada, and to address the inequities - to draw out the specific experiences of black folk.

The second thing, there's a debate about whether we should have Viola Desmond on the currency given the socio-economic experiences of black people. "You celebrate us on the currency, meanwhile, many people are living in poverty or underemployed or experiencing wage discrepancies." But in my view, it makes visible this history to everyday people who use that currency and maybe invites people to think of other stories that we don't know about. Black History Month allows us to tell these stories and remind Albertans and Canadians of the many more stories yet to be uncovered and told.

Related: Descendant of Alberta's black settlers documents rich heritage (UAlberta News)