Hot Days in the City

Elizabeth Chorney-Booth - 1 February 2024

When we look out our windows, we can see that the effects of climate change are no longer part of some potential, far-off future. The smoke from wildfires across Western Canada last summer was overwhelming, and a dry winter threatens more of the same. Terms like “heat dome” and “atmospheric river” are common. Flood mitigation is a permanent and ongoing concern in parts of the world, while European rivers have experienced unusually low water levels, thwarting tourism and the transport of goods.

But even as Canadians order air purifiers to protect themselves from the wildfire smoke that leaves the sky a shade of muddy orange, and Albertans had less cause to use their snow shovels this winter, it’s easy to think of climate change as a faraway problem, in a burning forest or on a melting glacier. For the most part, if you live in an Albertan city it’s easy to feel safe from the most drastic effects of climate change, even as we acknowledge that cities are contributors to the problem. But our municipalities are getting hotter, too. They are subject to floods and droughts; every Albertan remembers the 2013 Calgary flood and 2016 Fort McMurray wildfires. The very skeleton of our cities — concrete — acts as a barrier to water absorption, allowing rainwater to pool. And it’s a trap for heat, acting like a radiator on a hot day. Cities create a hefty carbon footprint.

“I teach a pretty large second-year sustainability class, and I always start by noting that I’m a part of the problem when it comes to climate change,” says Robert Summers, director of the University of Alberta’s School of Urban and Regional Planning, noting that he drives a car to work and heats his home with the same gas-fired furnace system that most Albertans use. “My lifestyle is not sustainable, even though I’m a firm believer in our need to act on climate change, but I live in a world where functioning in a normal way causes me to have an unsustainable environmental impact.”

Summers is far from alone. Living in most 21st-century North American cities requires driving to places or having things driven to us, heating homes when it’s cold and (increasingly, even in Canada) cooling them when they’re too hot. Plus, the level of consumption that drives our collective culture creates a whole lot of garbage. Sandeep Agrawal, an Earth and Atmospheric Sciences professor and associate dean of the Faculty of Graduate & Postdoctoral Studies at the U of A, says that cities are responsible for 60 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. This is partly because so many of us live in an urban environment and more people using things naturally results in more emissions. But there are also specific problems with the way urban developers planned how our cities function.

Agrawal, who was the first director of the School of Urban and Regional Planning, says that not only do cities contribute to the global weather trends that are melting glaciers and causing extreme weather events, but we’re also feeling the effects of changing weather within cities themselves. “And housing in high-latitude cities like Edmonton contributes higher greenhouse gas emissions than transportation, contrary to the prevailing belief,” he says. “Buildings contribute almost 45 per cent more than the transportation.” He studies a phenomenon called global heat islands, which can raise the temperature within a dense urban area by several degrees during a hot spell. If you’ve ever felt like the atmosphere is sweatier and more stifling downtown during the summer than it is in rural areas, it’s not your imagination.

“Urban heat islands cause a difference of temperature between a rural area and its urban counterparts,” he says. “Essentially, concrete, asphalt, fewer trees and more buildings all combine to increase the land surface temperature. When we see heat waves across B.C. and Alberta, they get exacerbated in the cities by the heat-island effect.” In 2021, Western Canada experienced a heat dome that the B.C. coroner said claimed more than 600 lives in the province, mainly in cities, and mainly in neighbourhoods that offered little respite from the heat, such as a green canopy.

The good news is that when we have a lot of people in concentrated areas creating the bulk of the world’s emissions, those same people can make an impact in the opposite direction by collectively changing behaviours. There are two things cities have to do in response to climate change: mitigate it and adapt to it. Mitigation, which is proactive, means decreasing emissions so that climate-caused changes don’t continue to worsen. Adaptation, which is reactive, means taking steps to protect citizens from weather-related damage caused by climate changes that are already well in motion.

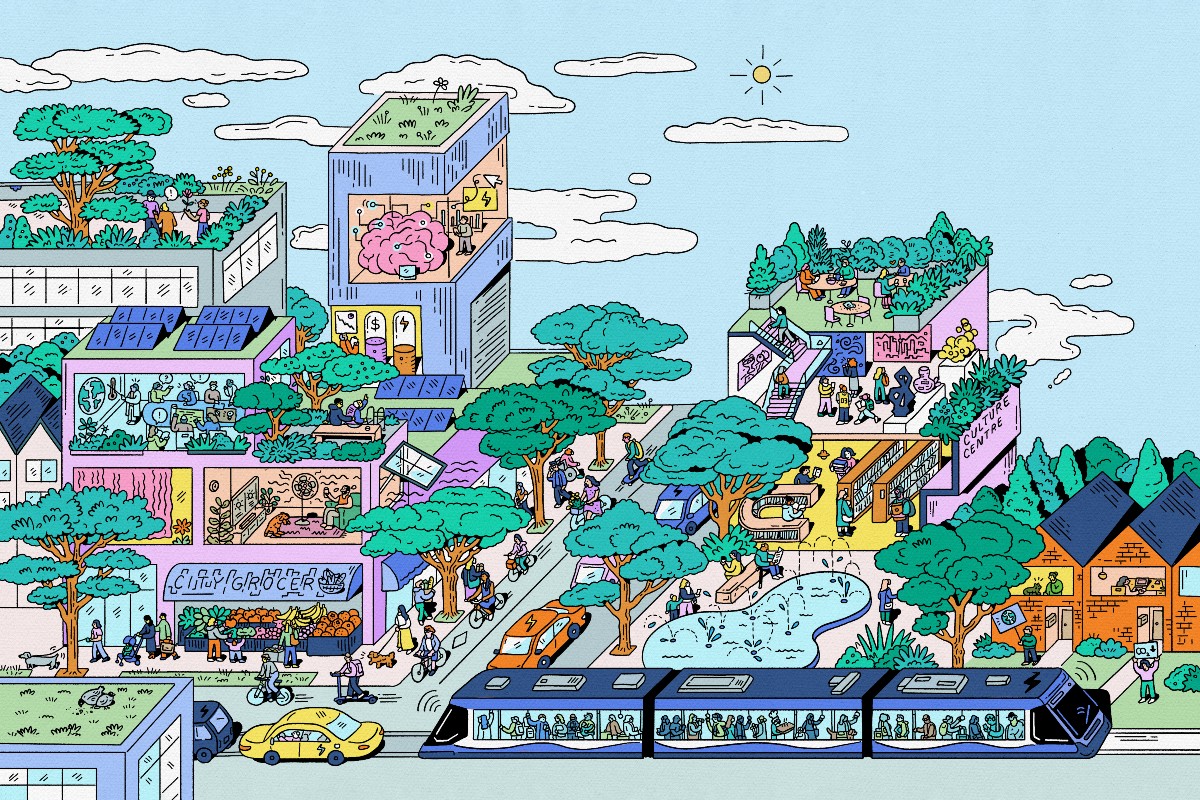

Summers believes changes to transportation are an important part of the mitigation effort. Cars are a culprit here and, while more public transport is a good step, creating greater urban density is also important so that cities don’t end up with large buses chauffeuring two or three people at a time out to far-flung suburbs. This doesn’t need to come in the form of a dramatic overhaul — easier access to transit, municipal zoning changes to help build density and more dedicated entertainment zones to give people a walkable place to go when they want to take in some culture can make a big difference. This is especially true if we factor in eventual technology-based moves to cleaner energy and technological advancements in electric and automated vehicles.

“We can plot out what a more sustainable city looks like,” Summers says. “It is denser in large part. Certainly, there are more opportunities for people to live in multi-family buildings where many people share walls and sometimes ceilings and floors. When you are more packed together, it’s often easier to walk or bike to places or use public transit.”

Compact cities help eliminate unnecessary transportation, and research shows they should be accompanied by other measures. Both Summers and Agrawal advocate for ample shady green spaces to give people a place to cool off outside, mitigating the urban heat-island effect. Other heat mitigators include water features, parks, local-species tree canopies and building practices that include roofs made of reflective rather than heat-absorbing colours and materials, or are planted with greenery. Some cities may need to implement infrastructure changes, such as more robust stormwater systems, flood barriers and dams where necessary.

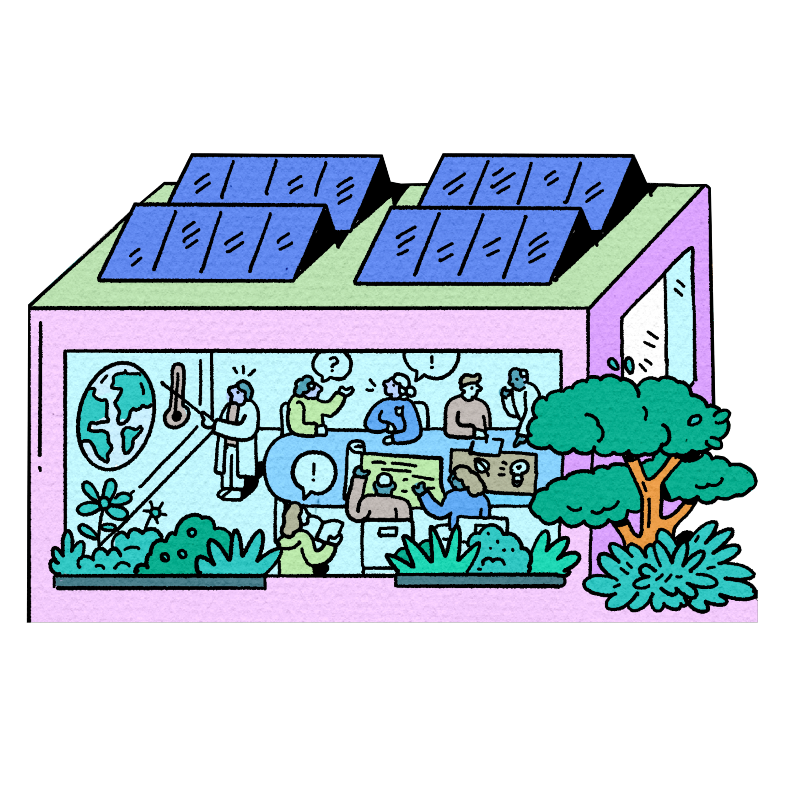

This research into creating sustainable cities is essential, but knowing how to help cities mitigate and adapt to climate change is only part of the equation. Realistically, getting citizens and governments to act on those recommendations is its own uphill battle. Researching public opinion and questions around policy is of interest to Jeff Birchall, director of the University of Alberta’s Climate Adaptation and Resilience Lab. Birchall researches the effect of climate change on communities and how people in those communities can address it. His efforts are more in the realm of adaptation than mitigation. “It’s about balancing the two. We’re always going to have to adapt, so we need to sort out the best approach,” he says. “That means collaboration between all levels of government, because each level of government brings different strengths.

Coming to a consensus on what those impacts might be and how to adapt to them is not just a matter of recognizing that lower emissions are better than higher emissions, that density is better than sprawl, or that spending money on mitigation and adaptation today will likely save money in the future. Birchall, whose work involves interacting with urban communities across Canada, particularly on coastlines, says that not only do citizens, politicians and commercial interests often disagree on how to allocate money and solve problems, but they often don’t even identify the same things as problems.

We contribute to and are affected by greenhouse gases unequally. Agrawal says affluent neighbourhoods are bigger emitters because of the large building footprints and higher use of private vehicles. But lower-income neighbourhoods feel the heat more acutely. Seniors with lower income might feel the health effects of hot summers when they leave windows open to manage the temperature inside, introducing wildfire smoke. Their major concern may not even register for suburbanites with air-conditioned houses and shady yards.

Overcoming those discrepancies and identifying community-wide concerns is important, but Birchall says the way various groups and people go about advocating for their personal priorities can make or break healthy policy discourse. Fighting and finger-pointing does not accomplish as much as looking for points where different parties’ interests may intersect.

Birchall recently presented some of his findings to Canada’s standing Senate committee on transport and communications. He told the committee that support from higher levels of government is crucial to motivating local governments and communities to plan for climate change.

“Local governments, as the level closest to the people, are in the best position to address climate change adaptation,” he says, “but it often comes as a downloaded responsibility without appropriate support.” In the case of infrastructure, he says, higher levels of government support the initial stages of development, while local communities can struggle to maintain it. “Ultimately, there’s a need for greater provincial initiatives to support local governments in adaptation.”

“We can’t solve this problem by fighting with people who don’t believe in climate change, because that’s a non-starter,” Birchall says. “We have to help people better understand that it is something that’s important, that it is going to cost them moving forward and that they’ve got a role to play.”

People usually want to do the right thing, to make good decisions. Birchall says the best way to ensure it happens is to build climate adaptation into regional policies. That way, it’s there for planners to use when they make decisions.

For Birchall, better policy planning means taking a multidisciplinary approach to research — bringing in the perspectives of environmental scientists, but also social scientists, health-care specialists, economists and more — while also consulting people in the community who may otherwise go unheard. In the same vein, Kyle Whitfield, a professor with the faculty’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, is participating in a study led by Shelby Yamamoto in the School of Public Health for which she collected data from older adults who have suffered health problems as the result of climate change. To help put Yamamoto’s data into context, Whitfield conducted research among a group of adults with an average age of 76 living in Red Deer and Calgary.

Whitfield says that before Yamamoto’s study little research had been done on the opinions of older adults regarding climate change. People might assume that older adults aren’t as concerned about climate change as their younger counterparts who will see the effects that a changing climate brings into the latter part of this century. But Whitfield says the research she is carrying out for Yamamoto shows quite the opposite. The information the team is uncovering may prove to be valuable as policy makers make decisions about cities that will appeal to a wider swath of constituents. The research indicates that Albertans are much more concerned about addressing climate change than stereotypes about them indicate, but transforming those concerns into policy involves Albertans actively listening to each other rather than making assumptions about what people may think based on identity, political affiliation or occupation.

“In terms of their climate change reactions, the people I interviewed talked a lot about fears of the unknown and also about food insecurity, as well as their own well-being as it pertained to the smoke,” Whitfield says. “They said they cared for the younger generations and are concerned about the younger people that are coming up. Their views certainly should be part of changing policy. Older adults are a growing portion of our population and are also a group that is too often dismissed.”

Imagine if policy eventually fell in line with what researchers said cities needed to protect themselves and the rest of the world from climate change. What would these future cities look like? Technology may be the wild card here — driverless cars and alternative energy platforms could play a part in the physical infrastructure of a metropolitan centre in 2065 — but Summers doesn’t want people to expect a Jetsons-like makeover in our lifetime. One scenario would be more townhouses, duplexes, better public transit and easy-to-use bike lanes. If so, the Canadian city of tomorrow would appear to be a more efficient version of its current self.

“I suspect most cities will look quite a bit similar to what we have, but hopefully with some denser pockets and better connectivity between those dense areas,” Summers says. “Maybe we’ll have a shift towards train transport for outlying communities. But I think we’ll still see a lot of cars.”

Will that be enough to move the needle on climate change? Probably not in the sense that we’ll see a dramatic turnaround that will bring us back to “normal,” but most of the University of Alberta’s climate change researchers seem surprisingly optimistic about not only the survival of our species, but our cities’ ability to thrive. The combination of policy changes, new technology and a willingness to collectively adapt holds promise that things can — and will — get better, if we work at them together.

“We have responded to challenges before. We are resilient people,” Agrawal says. “But with climate change, it’s not just a few of us, the entire world needs to come together. Some positive changes are occurring, but we are not there yet. But I’m hopeful.”