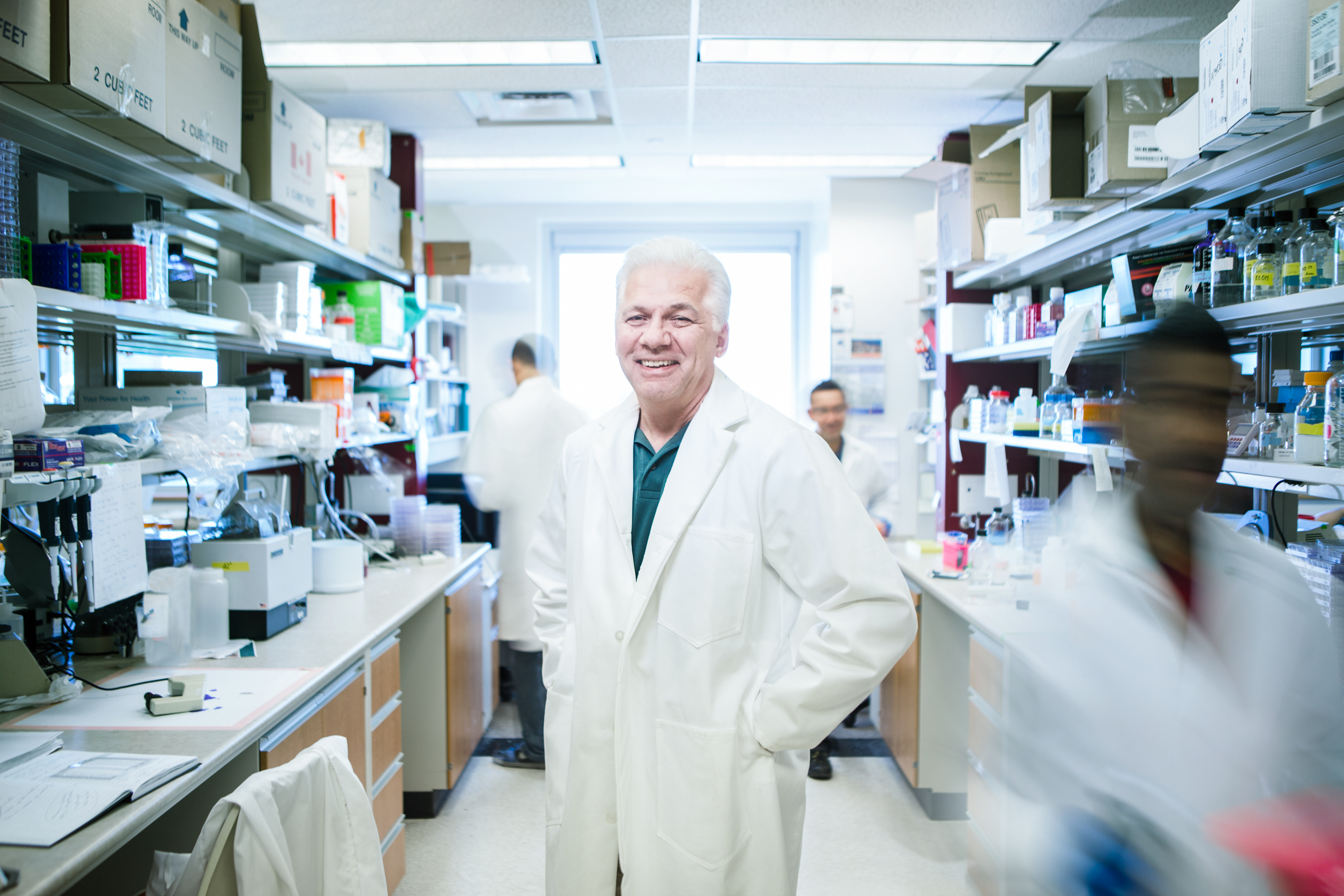

Tom Hobman is the Canada Research Chair in RNA Viruses and Host Interactions; Associate Dean, Research Facilities; Professor, Department of Cell Biology and adjunct professor, Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology. Hobman is a member of both the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology and the Women and Children's Health Research Institute at the University of Alberta.

For the past 18 months, Tom Hobman and his team have devoted much of their waking hours to a headlong pursuit of knowledge about the Zika virus. Hobman, professor of cell biology, is one of hundreds of researchers across the globe racing to stop the rapid spread of the mosquito-borne virus that entered the international spotlight in late 2015.

The Zika virus is a member of the flavivirus family - a group of viruses that also includes the West Nile and dengue viruses. First isolated in monkeys in Uganda in 1947, older strains of the virus were not recognized to cause serious disease.

That changed in May 2015, when an outbreak of the virus in Brazil coincided with a 2,700-per-cent increase in reported cases of microcephaly, an often-fatal congenital condition associated with incomplete brain development in newborns. Since the outbreak, Zika infections have spread at an unprecedented rate to every country in the Americas except Canada and Chile.

There are currently no antivirals or vaccines available to protect against Zika.

Leading the fight with international collaboration

Hobman's lab is among a select group of Canadian research teams that have received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to study the Zika virus. The University of Alberta team is collaborating closely with a group from the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, that has access to thousands of clinical samples.

"We are going to do what we're good at-cellular imaging and protein interactions-and they are going to do what they are good at―studying viral genomics," said Hobman. "The idea is to synergize our efforts and to accomplish more than we could individually."

Seed support critical to secure long-term Zika research funding

In July 2016, Hobman's team was awarded more than a million dollars over a five-year period from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to screen for antiviral compounds, and to develop research tools and diagnostics tests for Zika. In March 2017, CIHR contributed an additional $500,000 over three years for the lab to investigate how the virus changes host cells during infection, with the goal of developing antiviral therapies that can be used against the pathogen.

Hobman says his team's success in attracting major research funding from CIHR stems from the early support of the U of A's Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology and the Women and Children's Health Research Institute (WCHRI). The support from WCHRI was funded through the Stollery Children's Hospital Foundation and supporters of the Lois Hole Hospital for Women. "The seed funding was critical," said Hobman. "It allowed us to start doing experiments right away. Generating a lot of preliminary data allowed us to secure long-term funding."

Hunting down a persistent culprit

Hobman is investigating one of the key characteristics of the Zika virus―its ability to persist in the body for months at a time. The trait sets it apart from other mosquito-borne viruses, which are typically cleared out by the immune system within a week or two. By understanding that process, he hopes to develop a way to block the virus' persistence in the body.

While the work that is required to stop the Zika virus remains daunting, Hobman is encouraged by the enormous progress already being made by the world's scientific community.

"The pace of discovery is absolutely breathtaking. It's just fantastic to see how quickly things move when there is funding available. It's really remarkable. I don't think I've ever seen anything like this."